Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR – 6 February 2015

This week’s curation of legal news from the netosphere includes a relaunch of the CSA inquiry, a rethink of QASA, a battle of jurisdiction over the hangman’s noose, a parade of privatisation problems and a tussle of Tudor Thomases. But first, some other recent posts of interest: Guest post by David Burrows: Family legal aid… Continue reading about Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR – 6 February 2015

This week’s curation of legal news from the netosphere includes a relaunch of the CSA inquiry, a rethink of QASA, a battle of jurisdiction over the hangman’s noose, a parade of privatisation problems and a tussle of Tudor Thomases.

But first, some other recent posts of interest:

-

Guest post by David Burrows: Family legal aid and funding: January 2015

-

150 Years of Case Law on Trial: vote for the precedents you say take precedence

UPDATED 16 February 2015

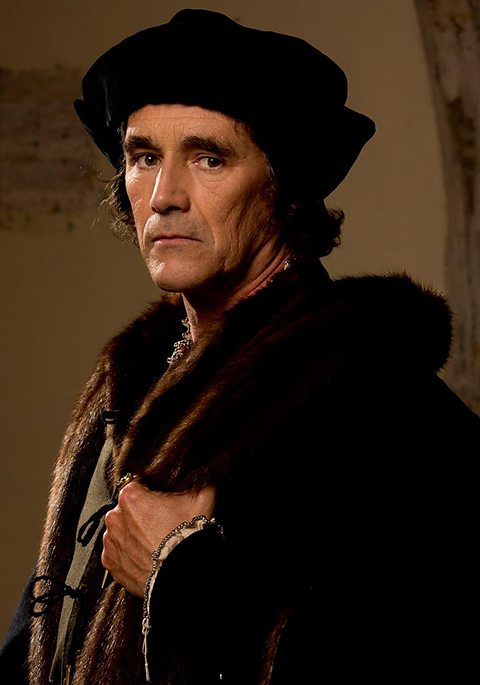

Wolf Hall: modern parallels?

If you have been watching the adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s novelisation of the life of Thomas Cromwell on TV, I wonder whether you, too, have wondered about the parallels between the political situation in Renaissance England and that of the present day.

Then, as now, you had a governing faction which felt increasingly uncomfortable and frustrated at the influence exerted within the realm by an unelected body in Europe (the church of Rome then, the European courts now), and which struggled towards a process of separation from the yoke of such foreign powers and an assertion of domestic sovereignty. English votes within English moats, the cry might go up.

The frustration of Henry’s claim to be able to divorce and remarry at will to get an heir, and so ensure the peace, order and good government of his realm, can be compared to the frustration of the current government in not being able to punish domestic offenders (or deport foreign criminals) with appropriate severity. But at least we don’t put them on the rack, or burn them at the stake.

My musings on this topic are not quite as fanciful as you may think. In the Tablet, Eamon Duffy (professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Cambridge) objected to Mantel’s depiction of St Thomas More as a “blood-soaked hypocrite” who tortured heretics to get them to recant, saying that More

viewed the preaching of heresy as we do the peddling of hard drugs, a moral cancer that ruined lives, corrupted the young, dissolved the bonds of truth and morality, and undermined the fabric of Christian society.

Duffy accepts that

In the age of Islamic State and al-Qaeda, we are deeply suspicious of anyone who thinks God wants us to kill other people, whatever the motive. But More’s world was not our world. By the standards of his age, he was a compassionate and just man.

With respect to Professor Duffy, I’d turn that round a bit and use the al-Qaeda bit to compare heresy to fundamentalism, and treason to terrorism. It’s not so much a moral issue as one of national security. Looked at thus, how different were More’s use of the rack and the fire from contemporary waterboarding and the electric prod?

Wolf Hall also gives us the opportunity of contemplating two different predecessors of our current Lord Chancellor, who is neither a man of the church, like Cardinal Wolsey, nor a man of the law, like Sir Thomas More. As for Thomas Cromwell, he was never Lord Chancellor, though he occupied a number of other high offices, such as Lord Chamberlain, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Master of the Rolls.

If you have your own ideas about the potential modern parallels and the inspiration behind the book, you can ask Hilary Mantel herself, when she appears at Middle Temple in a members-only event organised by Justice, on 11 February 2015.

Prisons and Probation

Privatisation on parade

One of the big successes the Lord Chancellor, Chris Grayling, hoped to achieve from his time in office was what he called his “Rehabilitation revolution”. However, almost no one involved seems to agree. He began with a good idea, which was that offenders serving sentences of less than 12 months in prison should be supervised on release to reduce the currently high level of reoffending among that group. The previous probation regime only covered those serving longer sentences.

What Grayling has done is to split probation into two areas. The most serious offenders (about 30%) will continue to be dealt with by the (public sector) National Probation Service. The low and medium risk offenders (about 200,000 of them) will now be dealt with by private contractors or “community rehabilitation companies”. They will be paid by results. But the process of privatisation has given rise to problems, not least a lack of communication and clear understanding of who does what and how. Overwork in both the companies and the service has led to dangerous cases being missed, it is said.

Some of the problems were highlighted in a report in December by the Chief Inspector of Probation, Paul McDowell, who said

the speed of changes to the service [had] “caused operational problems that could have been avoided or mitigated”… He said they exposed existing flaws in the system, including shortfalls in “processes, practice quality, consistency, leadership and management”.

For more information, BBC Probation reforms ‘moving too quickly’, inspector warns

See also, two blogs by Ian Dunt in Politics.co.uk

- Officers say public are in danger – so why won’t MoJ publish its safety test?

- Not even the MoJ understands what it is doing today

But, in another headache for Grayling, this week McDowell was compelled to resign his post, over a conflict of interest created by the fact that the company of which his wife is managing director, Sodexo Justice Services, has won the largest number of contracts to provide probation services. Sodexo took over the contracts in partnership with Nacro, the crime reduction charity, of which McDowell was the former chief executive.

According to the Guardian,

The resignation of the chief inspector of probation follows an announcement in December that Grayling would not be renewing the contract of the chief inspector of prisons, Nick Hardwick, amid speculation that he was too critical for the justice secretary.

Losing one chief inspector may be considered unfortunate. Losing two begins to look like carelessness.

CSA inquiry latest

Accident-prone probe re-reborn as judge-led statutory inquiry

Third time lucky, you could say, for Home Secretary Theresa May, as she announced in Parliament the re-launch of her ill-starred inquiry into historic child sex abuse. The inquiry was first set up in July last year, but the initial choice of chairperson, retired judge Baroness (Elizabeth) Butler-Sloss, was pressured into recusing herself by reason of her connection, as his sister, to the former Attorney General, the late Sir Michael Havers, whose actions would have come under scrutiny in the course of the inquiry. Her successor was the now former Lord Mayor of London, Fiona Woolf, a solicitor, but she, too, had to recuse herself as chairperson after it became clear that her occasional social engagements with former Home Secretary (now the late) Lord (Leon) Brittan QC, compromised her apparent objectivity.

In both cases, there was not only criticism of the choice on grounds of apparent bias, as I think it should properly be characterised (ie no suggestion of actual bias, just a matter of avoiding the suspicions of the reasonable bystander) but also a lot of hot air about the so-called Establishment, which means in general whatever the person complaining about it wants it to mean, eg a thinly veiled conspiracy of influence and patronage by those in positions of power and responsibility, against those not in such positions. (In Soviet Russia this was known as the Nomenklatura; now the same people form the Oligarchracy.) (See, generally, Weekly Notes 11 July 2014, and CSA Inquiry – will chair be shown the door?)

So, as I said, third time lucky, Theresa May has now taken up my own suggestion (on Twitter) of a New Zealand appointee. (In fact, I nominated Dame Sian Elias, but as Chief Justice of New Zealand she is probably too busy.) In geographical terms, you can’t get much further away from the British Establishment, whatever that is, and the new appointee, High Court judge Lowell Goddard, has the additional kudos of Maori ancestry. (Indeed, she was the first woman of Maori descent to be appointed as a High Court judge, in 1995.)

She has previously led an inquiry into police handling of child abuse cases in New Zealand during her terms as chair of the Police Complaints Authority. According to my contacts in the country, “everyone refers to her great experience of criminal law”, though whether that is meant to suggest a lack of experience in other areas is unclear. I am also reminded that the last NZ judge on a UK inquiry was (Edward) Somers J on the Bloody Sunday inquiry and he “resigned in despair after several years as it was eating up his retirement!” (It was said at the time to be “for personal reasons” because of the separation for long periods from his family back home).

The Saville Inquiry was set up in 1998 and was expected initially to last about 18 months, but this was revised to more like 5 years at the time when Somers J chucked in the towel. It eventually took until 2010 to report its findings – some 12 years, and cost nearly £200m. Let us hope Justice Goddard can keep better control of things. We wish her well. However, the fact that he inquiry is now, like that of Lord Saville, a statutory one, in this case under the Inquiries Act 2005, while giving it more powers, can make it take longer. According to the BBC report of the announcement:

Mrs May said Justice Goddard was a “highly respected” member of the judiciary and an “outstanding candidate with experience in challenging authority in this field”.

“We must leave no stone unturned if we are to take this once in a generation opportunity to get to the truth,” she said.

Justice Goddard will face a “pre-appointment hearing” before the Home Affairs Committee of MPs on 11 February to ensure “further transparency”, Mrs May said.

QASA latest

BSB explores alternatives to controversial Quality Assurance Scheme for Advocates

Last week the Bar Standards Board announced that, while an application for permission to appeal remains pending before the Supreme Court, challenging the lawfulness of the Quality Assurance Scheme for Advocates, and given the uncertainty over when the matter might be determined, the BSB would now explore “other ways in which we can properly protect the public from poor standards of advocacy”.

Given that the scheme itself, which was launched back in 2011, has been mired in controversy , and that the opponents’ application for judicial review of the scheme was decided by the Divisional Court over a year ago, it seems a little tardy only now to be considering an alternative approach. Whatever it is, it will need to do a lot better than QASA to reassure the concerns of practitioners, huge numbers of whom refused to register even when it was made compulsory (it is currently suspended).

It’s perfectly true that the Court of Appeal also rejected the claim for judicial review, on appeal from the Divisional Court: see Weekly Notes, 10 October 2014. The likelihood of the Supreme Court affirming both decisions is therefore high, or to put it another way, the chance of it going the other way, finally, seems remote. But they haven’t simply rejected the application. Yet. And that seems significant.

See also: Gazette

UPDATE: 16 February. Supreme Court grants [permission to] appeal to criminal barristers over QASA, reports Solicitors Journal. So the hearing will now go ahead, although the grounds on which permission was granted are limited to the correctness of the assumptions made by the Court of Appeal that the Services Directive is applicable and that QASA is an “authorisation scheme”, and as to the proper disposal of the appeal if the Court of Appeal’s approach to its role was too narrow; but the Supreme Court declined to hear on all other grounds – including whether the scheme compromised the independence of the advocate – on the basis that they had ‘no real prospect of success’.

See also: BSB statement

Supreme Court decision

Law (and injustice) around the world

An alphabetical tour d’horizon

France

Charlie Hebdo cartoonist “sad” at Saudi hypocrisy

In a recent interview with Vice News, Charlie Hebdo cartoonist Renald ‘Luz’ Luzier noted that in Saudi Arabia blogger Badawi has been sentenced to ten years in jail and 1,000 lashes. Yet,

“All of a sudden, Saudi Arabia says, ‘I am Charlie’, but it is not. They are not Charlie when they put a blogger in jail and whip him….It makes me really sad.”

Luz depicted the prophet Mahomet in his cartoons but said he didn’t think most Muslims cared about Charlie Hedbo. He said people who claim all Muslims are offended take Muslims for imbeciles, adding: “We don’t take Muslims for imbeciles.”

He was disappointed that powerful newspapers like the New York Times didn’t have the guts to reproduce the cartoons while trumpeting their “Je suis Charlie” credentials.

However, they are not hard to find on google.

Additional source: UK Press Gazette, Charlie Hebdo’s Luz talks of sadness at Saudi Arabian presence on Paris march in wake of 1,000 lashes sentence for blogger

Libya

Repeal of law banning Gaddafi-era officials from public office

“Why is Libya lawless?” asks a link on the BBC website. It explains that the country is not so much governed as overrun, by competing armed gangs. The much-vaunted Arab Spring has replaced the despotism, as many saw it, of Colonel Gaddafi, with anarchy and mayhem. When Gaddafi was overthrown, a law was passed by the country’s fragile democratic parliament in Tripoli banning any Gaddafi-era officials from taking part in politics. This is now regretted, and the only internationally recognised parliament in Libya, which is in Tobruk, and is opposed by the Islamist-led militia who have taken over Tripoli, has now decided to repeal the “political isolation law”. It is unclear, however, what effect this might have, given the nature of the politics in which the former regime’s officials have hitherto been banned from participating.

Source BBC: Libya revokes bill which banned Gaddafi-era officials from office

Mexico

Captured drugs lord could be extradited to US in “300 or 400 years”

Don’t hang around at the airport, I’d say. For according to a report in US News, the Sinaloa drug cartel leader Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, captured by Mexican marines last year, will not be extradited to the United States “anytime soon”, according to Mexico’s Attorney General, Jesus Murillo Karam.

He said he was expecting to receive a formal request from the US authorities, following calls by US congressional leaders. There are complaints pending in at least seven U.S. federal courts involving allegations that Guzman was masterminding smuggling operations to bring drugs into the country.

“I could accept extradition, but at the time that I choose. ‘El Chapo’ must stay here to complete his sentence, and then I will extradite him,” Murillo Karam told The Associated Press in an interview. “So about 300 or 400 years later — it will be a while.” Murillo Karam later clarified that he was referring to the time that it would take for Guzman to complete his sentences, “given all the crimes he’s being prosecuted for.”

For more on this, see also Fusion: Mexico might extradite Chapo Guzman in 300 or 400 years

Scotland

Tougher regime for serious offenders

Scotland’s first minister, Nicola Sturgeon has announced plans to tighten up proposed legislation to end the current system of early release for anyone serving more than four years in prison. Under the Prisoners (Control of Release) (Scotland) Bill, which is currently making its way through the Scottish Parliament, sex offenders and anyone sentenced to ten years or more will no longer be eligible for automatic early release two-thirds of the way through their sentence. However, Sturgeon now wants to extend that to anyone serving more than four years.

She added: “As an additional safety measure, I can also confirm that we will introduce a guaranteed period of supervision for these long term prisoners, to be set out as part of their sentence, which will aid their rehabilitation and help them reintegrate into communities.”

Source: the Scotsman, Sturgeon gets touch on early release for prisoners

Trinidad and Tobago

Seven-judge committee to rule on death penalty jurisdiction

A seven-judge board of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC, or PC) is to hear the appeal of two men who in 2008 were convicted of murder and sentenced to death in Trinidad. Their appeals to the Court of Appeal of Trinidad and Tobago were dismissed. The case details on the PC website doesn’t go into the grounds for their apeal to what amounts to the court of final appeal for the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago (so arguably not really a British court at all) but one of them relates to the constitutionality of the PC in varying the death penalty imposed by the Trinidadian court.

By reason of an earlier decision of the PC, Pratt v Attorney-General for Jamaica [1994] 2 AC 1, in which it was held that to carry out executions after a prolonged delay constituted “inhuman punishment“ in breach of the constitution (of Jamaica in that case), neither appellant was likely actually to be hanged in the present case. But according to the Guardian,

the issue at stake relates to the continuing judicial dispute between the Caribbean and London over who should have power to commute a death sentence.

Most West Indian states whose final appeals still come to the PC no longer impose the death penalty, and some now send their appeals to the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), a local court of final appeal intended, ultimately, to replace the PC for all the jurisdictions in the region. If Trinidad does not currently send its appeals to the CCJ, that may be because the necessary amendment of the Constitution of Trinidad and Tobago has not been effected, as was the case for Jamaica, at the time of the PC’s ruling in Independent Jamaica Council for Human Rights (1998) Ltd v Marshall-Burnett [2005] UKPC 3; [2005] 2 AC 356 (a case I reported myself, back in the days when the PC sat in Downing Street).

However, it is not just a question of jurisdiction to hear the appeals. The state’s lawyers want to overturn a recent decision which allowed a domestic court in Trinidad to commute a death sentence after a five-year period had elapsed. Instead, the state wants the men to petition the state president or apply to the High Court in the capital, Port of Spain, for the sentences to be commuted.

Although local politicians in the Caribbean chafe at the notion of a court in London supervising their own judiciary, regarding it as a “relic of the British empire”, those who campaign against the death penalty argue that the objectivity of the PC enables rational constitutional and human rights decisions to be made, free of political pressure, and that its decisions have influenced the jurisprudence of courts around the world, such as Kenya, Uganda and Malawi, which have, in turn, commuted death penalties. (See, on this, another article in the Guardian: West Indian death row prisoners to be defended by British lawyers )

UPDATE: Just seen in the latest Counsel magazine, on subject of Caribbean Court of Justice, a nice interview with its current president, Chief Justice Sir Dennis Byron.

That’s it folks! (No celebrity fluff this week – sorry.) Enjoy the weekend, and don’t forget to sign up for weekly Case Law Updates. Click here for last week’s alert.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content at ICLR. It does not necessarily represent any views of ICLR as an organisation.