Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR, 25 January 2021

This week’s roundup of legal news and commentary includes a departmental audit for the MOJ, coronavirus cases from other European jurisdictions, anti-genocidal trading policy, domestic abuse in the Court of Appeal, and help for legally unaided litigants.

Ministry of Justice

Departmental overview by NAO

Earlier this month the National Audit Office published its Departmental Overview 2019–20 for the Ministry of Justice. The overview summarises the work of the department including what it does, how much it costs, recent and planned changes and what to look out for across its main business areas and services.

The survey covers the department’s main areas of activity: courts and tribunals, legal aid, prisons, parole and probation. It assesses what the MOJ itself aims to achieve, its departmental goals; and flags up some particular issues for the immediate future. These include:

- Spending on Brexit — between June 2016 and January 2020 the Ministry had spent £39 million on EU Exit preparations. It spent another £2m in 2019–20 deploying over 150 staff across government to support preparations for leaving the EU.

- Court Reform — HMCTS’s focus on keeping courts and tribunals running during the COVID-19 pandemic “has impacted timelines for delivering its reform programme”. However, in some areas the response to the pandemic has accelerated reform, notably in respect of “progress on the implementation of video technology and digital capabilities”.

- Probation service — In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, in June 2020 HM Prison & Probation Service (HMPPS) revised its approach to the Transforming Rehabilitation project (ending its problematic contracting out to Community Rehabilitation Companies), and “now plans to bring the management of unpaid work and accredited programmes within the remit of the National Probation Service, rather than contracting these services to delivery partners”.

- Prisons expansion — The NAO report Improving the prison estate (February 2020) found that HMPPS had not provided enough places, in the right type of prisons and at the right time, to meet demand. In August 2019, the government announced a new programme of up to £2.5 billion but in the 2020 Spending Review in November 2020 it increased this investment to more than £4 billion to deliver 18,000 modern prison places.

There are other interesting bits of information. For example, in terms of diversity, it records that in 2020 there were 54% female staff to 42% male; that there were 13% disabled (as they describe it) staff (up from 6% in 2015) in the department as a whole, but among “senior civil servants” there were only 9% disabled (up from 6% in 2015). In terms of ethnicity, this is broken down into three categories, all staff (14% BAME in 2020), senior civil servants (6% BAME) and “court judges” (doing rather better than the senior civil servants, with 8% BAME — up from 6% in 2015).

Court reform & coping with Covid: can’t do both?

Since the NAO departmental report, it appears that one of its senior officials, Yvonne Gallagher, the NAO’s director of digital, speaking at a virtual Westminster Legal Policy Forum recently, had “queried the wisdom of pressing ahead with broad reforms and whether it was possible to implement them alongside the daily demands of keeping the justice system running”. According to a report of the event in Legal Futures,

“She questioned whether the scope of the reform programme was realistic in the published timescale. The programme was extended from four to six years before it was signed off and last March it was announced that the completion date would be delayed by a further year to 2023.”

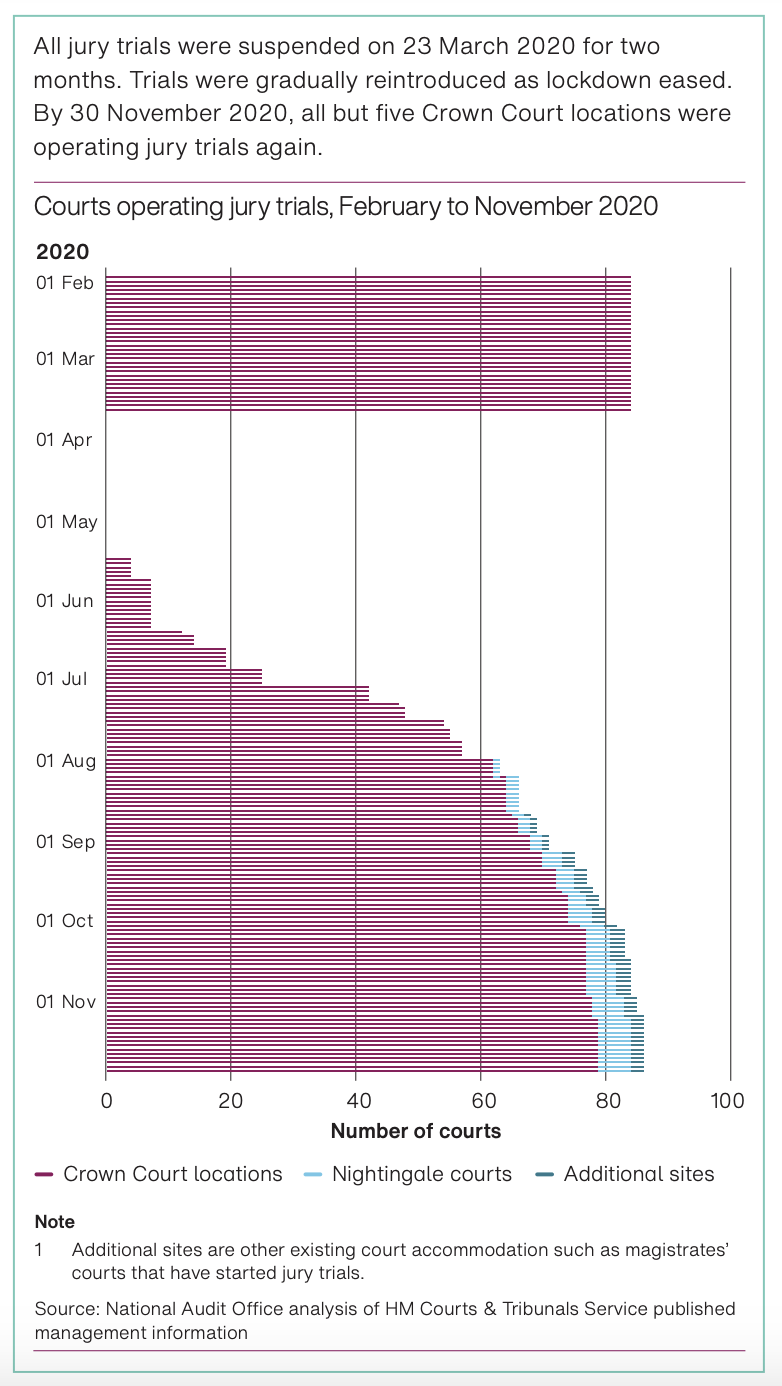

Since its launch in 2016 the £1 bn-plus HMCTS Reform project has certainly generated a lot of comment (including on this blog), but even the delays and overspends have always been robustly defended and justified by those managing the project (which is really about 50 different sub-projects under one giant umbrella). It is a notable fact that, although HMCTS was not well prepared to face it, the coronavirus pandemic has boosted certain aspects of reform, particularly in the rollout of remote hearing technology. The other side of the coin is that the rapid prior sell-off of court rooms has made it that much hard to reopen socially distanced courts for those hearings that cannot be conducted remotely, though the addition of temporary “nightingale” courts has helped. There is an interesting infographic in the NAO report showing the gradual increase in reopened and temporary courts towards the end of the year:

This looks encouraging (and more have opened since November), but it can’t overlook the fact that (a) many of these courts don’t feel safe to users (as we reported last week), and (b) that there was already a massive backlog in long-delayed criminal trials well before the coronavirus pandemic hit the proverbial fan. This was the subject of an article by the Secret Barrister in the Sunday Times over the weekend, linked via this blog post: The delays in criminal justice were caused by government, not Covid.

See also: Monidipa Fouzder, Law Society Gazette, News focus: Are we putting court users in harm’s way?

Human Rights

Anti-genocide trade amendment defeated

Last week the government narrowly defeated (by 319 votes to 308) an all-party amendment to the Trade Bill, backed by a number of backbench Tory MPs and strongly endorsed in the Lords, which would have required the reconsideration of any trade deal with another country if the High Court found that country to be committing genocide. Hansard, Commons, Tuesday 19 January 2021

The amendment had been passed by the Lords with a majority of 129, and it is likely they will now try to reintroduce it in some form. Devised by Lord Alton, it has been widely supported by religious and human rights groups including the Conservative Muslim Forum, the British Board of Jewish Deputies, the International Bar Association and a number of Christian groups and campaigners. Lords Amendments to the Trade Bill (it is no 3).

The amendment appeared to have China in contemplation, where the treatment of the Uighur Muslim minority in Xinjiang has been alleged to constitute a form of genocide. Before leaving office, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had so declared, and Antony Blinken, his successor under the incoming Biden administration has endorsed that view (see BBC, US: China ‘committed genocide against Uighurs’).

As the UK Human Rights Blog explains in its latest roundup,

“The amendment aimed to deal with a current impasse whereby international courts cannot make a ruling on genocide because the involved nations, for example, China, veto such matters from consideration, or do not recognise the relevant courts. The Trade Secretary, Greg Hands, had strongly opposed the amendment, suggesting that it fundamentally undermined Parliamentary sovereignty in giving the courts too much power to determine UK trade deals.”

See also: last week’s UK Human Rights Blog, The Weekly Round-up: A British response to Uyghur forced labour

Guardian, UK free to make trade deals with genocidal regimes after Commons vote

European courts rule against lockdown restrictions

A German district court in Weimar has declared the prohibition on social contact under coronavirus regulations to be unlawful as contrary to the German Basic Law (Gründgesetz). The Infection Protection Act was not a sufficient legal basis for such a far-reaching regulation as a contact ban, which violated human dignity and had not been proportionate, the court ruled.

The case is the subject of a post by Rosalind English on the UK Human Rights Blog: German District Court declares Corona Ordinance Unconstitutional

In a further post, she comments on another case, this time from Belgium, where the police tribunal in Brussels, in a judgment on 12 January, acquitted a man summoned for non-wearing of a mask, because the enforced wearing of the mask in public space was unconstitutional.

“The judge recognised that the current health situation justifies a restriction of freedom of movement and the imposition of certain measures. However, he considered that these measures must have a legal basis — parliament had not legislated to authorise the restrictive measures taken by the various ministers since the beginning of the crisis — and that they must be compatible with the other rights in force.”

See: Rosalind English, Enforced wearing of masks declared unconstitutional

Family law

Domestic abuse

Last week the Court of Appeal considered four conjoined appeals where, it was said, the court’s approach to the handling of allegations of domestic abuse had been wrong.

In an earlier case, described on the Transparency Project blog as a “warm up act”, Mr Justice Hayden had traversed some of the issues likely to be aired in those appeals, and comprehensively set out the framework for consideration of allegations of ‘coercive and controlling behaviour’ (‘CCB’) (an increasingly recognised aspect of domestic abuse) before politely declining an invitation to issue guidance, no doubt mindful that there may be a rare opportunity for such guidance to be issued by his superior judges in coming days: see F v M [2021] EWFC 4.

Domestic abuse, the blog post by Lucy Reed explained, is

“pretty grim stuff and it has a really serious impact on its victims, be they adult or child. It does matter that these cases are ‘done’ properly. There is a current and persistent worry that issues of domestic abuse (including but not limited to CCB) are not being properly handled by the family courts, and there is an understandably high degree of interest in the topic — many hold hope these appeals may change something that so far endless reviews and media reports have failed to change.

The appeals hearing was conducted remotely and well attended via Microsoft Teams, both by media and public observers. It was live tweeted by the Transparency Project and George Julian, among others, and Joshua Rozenberg wrote about it (and Hayden J’s earlier judgment) here: What does domestic abuse look like?

The Court of Appeal judgment when it comes (it has been reserved) is expected to provide guidelines on a matter on which the last substantial guideline judgment was given more than 20 years ago.

See also, via Transparency Project: The Court of Appeal considers Domestic Abuse — Part 1 and Part 2 (part 3 will follow).

Domestic abuse is particularly problematic because of the way it overlaps both the civil law (family) and criminal legal systems, but with different standards of proof and different provisions for legal aid. It is also apparently on the increase, particularly under the pressures of proximity under the coronavirus lockdown over the last year.

According to the anonymous author of The Secret Magistrate, 11% of the crime committed in England and Wales is related to domestic violence and abuse.

A report by the London Assembly found that domestic abuse offences in London have nearly doubled from 46,000 in 2011 to 89,000 in 2019. They now account for 10% of all offences in the capital. Less than 15% resulted in a prosecution as many alleged victims do not proceed with a complaint, and only 6,896 domestic abuse related convictions in London were recorded in 2019–20.

In family cases, where it will be the subject of a fact finding hearing, the focus on not on the punishment of the perpetrator, but on protection of the victim in the home and of any children living with either of them or for whom the court might make arrangements for them to live with them.

Legislation

There is currently a Domestic Abuse Bill before Parliament, which today had entered its committee stage in the House of Lords. You can read the debate in Hansard. See also:

Mayor of London / London Assembly: Victims’ Commissioner warns Family Courts are failing children

“The Domestic Abuse Bill in its current form fails to protect children from the impact of domestic abuse and must be amended to remove the presumption of contact in order to provide better protection. Unsupervised contact should not be granted where Restraining Orders, Non-Molestation Orders or Protective Orders have been put in place against a parent. This Bill is a vital once-in-a-generation opportunity to protect survivors of domestic abuse, and the Government must ensure that protection extends to the Family Courts.”

Green World: Applying Green political philosophy to the Domestic Abuse Bill

See also: Stowe Family Law, Why are domestic abusers still cross-examining their victims in the family court?

Litigants in person

Government funding for support

A new MOJ and Access to Justice Foundation joint initiative has now awarded all of its funding, working with 11 new projects that cover more than 50 different organisations across England and Wales — providing advice and guidance to those without legal representation. Last week’s announcement from the MOJ said the distribution of funding marked an important milestone in the MOJ’s Legal Support Action Plan (launched in February 2019) for helping those who are representing themselves in court. The grant is working with partnerships of not-for-profit organisations, providing new routes to support at local, regional and national levels.

The organisations involved include Citizens Advice and local law centres. In 1949 there was a thing called Legal Aid set up by the government to fund legal advice and representation for those who could not afford it. Seventy years later that seems to have fallen out of favour. At any rate, far fewer people qualify for assistance than used to, and the amounts paid out have also been cut in the last decade. So instead, an increasing number of people who now can’t get legal aid have to represent themselves in court: the number of such litigants in person has massively increased in recent years, and now the government is providing funding (but not legal aid as such) to help them. This may seem contrary, but according to the action plan introduced by the previous Lord Chancellor, David Gauke,

“Legal aid plays an important role in supporting the most vulnerable, however this is only one part of the picture. A just, accessible and proportionate justice system demands that many elements — including effective frameworks of legal aid and legal support, a modern courts system where people can easily resolve disputes, cross government working, and a broad range of alternative methods of dispute resolution — must be brought closer together in a coherent way.”

The action plan and the new funding are therefore aimed at addressing the totality of support available to people from “information, guidance and signposting at one end of the spectrum to legal advice and representation at the other”. This part of the package appears to be addressing the early stages of that process, ie before specialist advice and representation are required (and presumably in the hope that they might not be).

Other recent publications

Advocacy podcast

The Advocacy Podcast: Journeys To Excellence is a podcast about trial advocacy. Barrister Bibi Badejo interviews the best trial lawyers from around the world about how they excel in the courtroom. Beginning with an inspiring episode featuring Prof Leslie Thomas QC, the podcasts introduce the listener to a series of top practitioners for their best tips on the art of advocacy.

Pleased to write my 1st piece for @prospect_uk – on who criminal barristers should be allowed to act for in wake of row over David Perry QC – with thoughts from @Kirsty_Brimelow @LordCFalconer @philippesands Helena Kennedy QC & Geoffrey Robertson QC https://t.co/ND8IwWimfR

— Catherine Baksi (@legalhackette) January 21, 2021

Who should barristers be allowed to act for?

Catherine Baksi in Prospect magazine discusses the obligations of a barrister to act for a problematic client, by reference in particular to recent criticism of David Perry QC for taking a prosecuting brief in a case brought by the Hong Kong authorities against a number of people, including prominent barristers and a newspaper publisher, over their support for recent pro-democracy protests in the territory. (Since our coverage of the case in last week’s roundup, Perry has now withdrawn from the case.)

“So what is the right way through? In making the decision on whether to accept cases, Philippe Sands QC, Director of the Centre on International Courts and Tribunals at UCL, says barristers might be guided by whether their engagement reinforces or undermines the rule of law. Where the underlying laws of the country or tribunal are consistent with the rule of law, or the case seeks to further it, he suggests, a barrister could be inclined to accept with a clear conscience. But where they are being asked to do something that manifestly undermines the rule of law — for example to prosecute individuals for actions that are lawful under any reasonable standard of national or international law — they should resist.”

The rule of law is in dire straits

One of the defendants in the Hong Kong case (above) is Dr Margaret Ng, member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong between 1995 and 2012 and a founding member of the pro-democracy Basic Law Article 23 Concern Group. In a recent IBA podcast she discusses the implications of China’s recently enacted national security law in conversation with IBA Multimedia Journalist Jennifer Venis: ‘The rule of law is in dire straits’ — Dr Margaret Ng on Hong Kong national security law

Disbarment, arrest and detention of lawyers in Tanzania

The Law Society has written to the president of Tanzania, John Pombe Maguful, expressing concern about attacks on lawyers and the independence of the legal profession in Tanzania, including disbarments, arrest and detention, and legislative proposals. The letter identifies a number of individual lawyers who have been targeted, urging reversal of disbarment and other proceedings taken against them. It also says:

“We’re especially concerned about recent efforts of the government to restrict the independence of the Tanganyika Law Society through the recent amendment of the Tanganyika Law Society Act, pursuant to the Written Laws (Miscellaneous Amendments) (№8) Act, 2019.”

What codification of Roe v Wade means and why President Biden is right to support it

David Allen Green on the Law and Policy Blog discusses a possible policy initiative by the newly installed Biden administration in the USA. Roe v Wade (1973) 410 US 113 was the decision of the US Supreme Court establishing a pregnant woman’s liberty to choose to have an abortion without excessive government restriction. The decision is at risk of being overturned by a more conservatively (pro-life / anti-abortion) constitution of the court, which is all the more likely since the appointment under the Trump administration of three more conservative judges. Codification would mean Congress (with a more liberal majority) placing the right on a statutory basis at the federal level.

Why the ECJ still has a role to play in Britain’s lawmaking

Steven Barrett, a chancery barrister in Radcliffe Chambers, explains to the normally quite Brexity readers of The Spectator why, although we are no longer bound by the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg, British courts might nevertheless still want to rely on its decisions and the law developed therein. “English law is a magpie,” he explains. It picks and chooses (copies and pastes) good bits of law from elsewhere and adopts them as part of the common law. “If the ECJ comes out with an outstanding legal argument” he says, “then we would be fools not to copy it.”

(Note: ICLR has no plans to cease reporting those cases from the ECJ which are likely to interest students and practitioners and to affect the law in our own jurisdiction.)

COVID-19: Confidentiality and working from home

The Law Society, as part of its coronavirus resources, has published an article by Paul Bennett, a solicitor and professional regulation partner at law firm Bennett Briegal LLP and a member of the Regulatory Processes Committee of the Law Society, who shares his expertise and tips on working while at home. He points out that “Working from home as most of us are, the challenges around privilege and confidentiality are different to those in the office.” He warns against the risk of compromising client confidentiality while working with documents in a shared and potentially less secure domestic environment.

Divorce post-Brexit

David Pocklington on the Law & Religion UK blog discusses a recently updated House of Commons Library briefing paper on the implications of Brexit for cross-border divorce disputes. Brexit may affect UK-EU cross-border divorces in matters such as where a divorce takes place and the recognition and enforcement of orders relating to divorce.

Dates and Deadlines

Holocaust Memorial Day concert

Opera Holland Park (online) — Wednesday 27 January at 6pm

Directed from the piano by Lada Valešová, tenor Nicky Spence and the Navarra Quartet will perform Pavel Haas’s song cycle Fata Morgana Op. 6. The performance will be preceded by a reflection on remembrance from the acclaimed author, Howard Jacobson. It can be watched online here.

Holocaust Memorial Day takes place on 27 January each year in memory of the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust, alongside the millions of other people killed under Nazi Persecution and in the genocides which followed in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia and Darfur.

And finally…

Tweet of the week

is from Middle Temple, where it may have snowed briefly yesterday, but it definitely snowed properly in the old days.

In the absence of a #WhiteChristmas in London, this image taken looking towards the snowy Middle Temple Garden, c.1935, provides a glimpse of the atmospheric winters of the past. #Archives pic.twitter.com/YlOUU8GOA0

— Middle Temple (@middletemple) December 25, 2020

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading, and thanks for all your tweets and links. Take care now.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content. It does not necessarily represent the opinions of ICLR as an organisation.

Featured image: Ministry of Justice HQ (via Google Streetview)