Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR – 24 October 2016

This week’s ragbag of legal news and commentary includes a pardon for the gaily innocent and a slap on the wrist for the deeply offensive, a capital anagram for the meaning of Brexit, morale boosting power for the justices, and a trial by battle of criminal textbooks. Turing’s Law Posthumous pardon for historic homosexual… Continue reading about Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR – 24 October 2016

This week’s ragbag of legal news and commentary includes a pardon for the gaily innocent and a slap on the wrist for the deeply offensive, a capital anagram for the meaning of Brexit, morale boosting power for the justices, and a trial by battle of criminal textbooks.

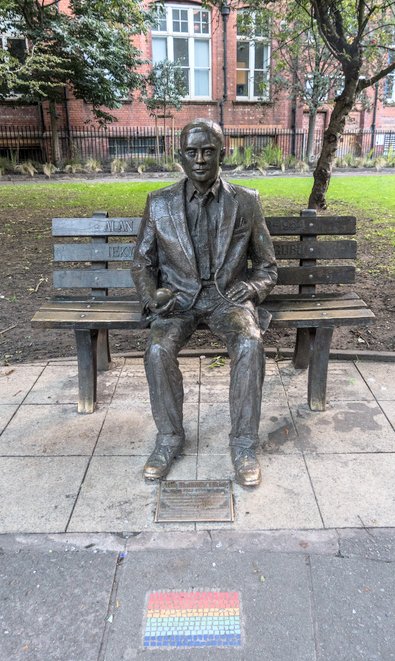

Turing’s Law

Posthumous pardon for historic homosexual offenders

Thousands of gay and bisexual men convicted of now abolished sexual offences will be posthumously pardoned, Justice Minister Sam Gyimah announced on 20 October, under what it being called Turing’s Law. Alan Turing was the genius codebreaker who played a major role in solving the Enigma enigma during World War II – only to be hounded and prosecuted for homosexual offences after the war he’d help to win was over. His suicide not long after is thought to have been prompted by his treatment. He was officially pardoned in 2013.

Making the announcement, the minister said that supporting Lord Sharkey’s amendment to the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 through the Policing and Crime Bill would be the quickest way to deliver this commitment, and rejected a rival proposal by way of a private members bill brought forward by John Nicolson MP which would not have involved a “disregard process” to check that the relevant offences would not still be offences today (because involving minors, say, or sexual acts in public lavatories, which are still illegal). Said Gyimah:

It is hugely important that we pardon people convicted of historical sexual offences who would be innocent of any crime today.

But is it? Carl Gardner, writing in response to the “pardoning” of Alan Turing, had this to say:

Peers and the government just want to do something symbolic. But who benefits from the symbolism? Not Alan Turing. This pardon, well-intentioned though it undoubtedly is, is not only pointless but self-indulgent. It would make only us only feel that we’re relieved of the burden of the past.

See also Gardner’s later post,Alan Turing: a strain’d quality of irrational and arbitrary mercy.

And now, in response to this later batch-process pardon for people not called Alan Turing but suffering the same institutional odium (the newsworthy example being Oscar Wilde), comes a similar objection from law blogger Spinning Hugo:

“To pardon someone is to forgive a wrong. […]

The laws in place in the United Kingdom criminalising homosexual acts were wrong and barbaric. Such consensual acts between people of the same sex wronged nobody. There were no good public policy reasons for criminalising their actions. Those who were convicted were themselves the victims of a wrong. There is nothing for the state to forgive or pardon, indeed to say that there is is to (literally) add insult to injury.

What the gov should do, he says, is retrospectively decriminalise these offences. But perhaps they fear the compensatory claims that might ensue (though they could be subject to reasonable limitation, he argues).

The only people who have the capacity to forgive are the victims of this injustice: the men wrongfully convicted.”

Another attempt to rewrite history

Interestingly, the move came in the same week as a vote by the Commons to strip Sir Philip Green, the asset-stripping business tycoon who sold BHS for a pound and left its pension short of funds, of his knighthood. Once again, the urge to look as if something is being done to put things right has got the better of people, but it may well have the undesirable consequence of excusing them from any more difficult but worthwhile restitutionary measures.

Moreover, entertaining as the debate probably was, not least for the MPs given a licence to let off steam about the “unacceptable face of capitalism” etc, the vote was particularly futile since it didn’t even have the benefit of actually having any effect (see The Week: Will Sir Philip Green lose his gong? with video). It will be for the Honours Forfeiture Committee to decide whether Sir Philip should lose his knighthood, itself a purely symbolic title left over from feudal times.

Press regulation

Is freedom of the press doomed or merely abused?

In a speech at the annual Society of Editors dinner in Carlisle, Sir Alan Moses, chair of IPSO said the free press in the UK would be “doomed” if the big powerful companies were forced to join a regulator that complied with the Leveson Inquiry recommendations, on pain (if they didn’t) of having to pay the costs of those forced to take their complaint to the courts instead, even if the complaint failed.

That is the effect of section 40 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013. Either you sign up to a proper regulator and take advantage of a low costs complaints mechanism approved under the Royal Charter, or, if you refuse to do so, you pay for the complaints to be heard in court. Judges would have a discretion not to allow such costs to a vexatious or speculative complainant, or one whose complaint was wholly unmeritorious. Judges exercise such powers all the time and if the press fear justice, they have only to sign up to a proper regulator.

Sir Alan, as a former barrister, is obviously putting his employers’ case in as strong and forceful terms as possible. But it’s quite hard to distinguish it from that of those litigants in person who, faced with a parking ticket in the mags’ court, assert that they are “freemen of the land” and that, by virtue of Magna Carta, and possibly some Lord of the Manor certificate purchased off the internet, they are NOT SUBJECT TO ORDINARY LAWS. He made this clear when, in another speech given recently (at the 5RB media chambers conference last month) he described media regulation as “that most oxymoronic of pursuits”. So the minute you regulate it, you stop it being a free press. Tinkerbell will die and we’ll all be the poorer. And his own job, as chair of a press regulator, is axiomatically oxymoronic.

But he is not alone. Leaders and columnists in all the major newspapers have been wailing and gnashing their teeth about the dreadful risks to the free world if the UK press isn’t allowed to go on running wild. Even someone as supposedly rational as Matthew Parris was at in the Times (£) on Saturday; in the shadow of a trenchant leader. (I mean leader as in content, not person.) Perhaps they should listen to something else Sir Alan Moses told the 5RB conference: “ shouty repetitive advocacy is unlikely to persuade anyone”.

It’s worth setting all their spoilt wailing against a couple of other egregious news items this week.

First, Mazher Mahmood, the so-called “Fake Sheikh”, darling of the News International story-generating sting machine, having been found guilty of conspiring to pervert the course of justice, was sentenced to 15 months imprisonment. Has also been sacked by News International, for whom he’s worked for a quarter of a century. (This presumably will not prevent him working “freelance” after he serves his sentence and repays his debt to society.) Many of the cases in which his undercover evidence has contributed towards criminal convictions are now to be re-examined. Victims of his stings are likely to bring civil claims for damages. (see BBC news report.)

Hacked Off, perhaps rather optimistically, regard the case as yet one more nail in IPSO’s coffin – with a lovely cartoon by Steve Bell.

Secondly, in the case of Manji v The Sun, IPSO has arguably demonstrated its own flagrant inadequacy as a regulator by deciding that the paper could legitimately publish something which was “deeply offensive” to the victim (Channel 4 news reporter Fatima Manji) and “caused widespread concern and distress to others” (about 1700 complaints were made to IPSO), after rejecting (in my view wrongly) allegations of religious discrimination and (perhaps less obviously wrongly) an imputation, against the observant Muslim reporter, of terror sympathy when presenting the news about a terror incident in Nice earlier this year.

In the Guardian (not a member of IPSO) one commentator suggested the IPSO ruling was “worse than the original column” complained about, because it legitimised “crude and blatantly Islamophobic thinking”. Manji herself responded (in a BBC interview) that the ruling meant it was “open season on Muslims”.

However, before we get too smugly censorious about all this, it’s worth asking whether IMPRESS — the only fully Leveson-compliant regulator, whose (imminently expected) approval by the Press Regulation Panel would trigger the implementation of section 40 — would have come to a different conclusion in this case. When I put this to Twitter, the response from Prof Brian Cathcart (a founding member of Hacked Off) was “Can’t say, but whichever way it found it would be more credible, because independent.” And that, surely, is the point. Self-regulation is, ultimately, self-serving.

See also:

- Inforrm’s blog, Ruling on Fatima Manji is further proof that IPSO fails as a press regulator – Alexander Brown

- Also on Inforrm’s blog, but earlier (and oddly prescient), ITN’s complaint to IPSO over hijab article is a waste of time – Brian Cathcart

Magistracy

Report of parliamentary Justice Committee

Commenting on the The role of the magistracy, the report published this month by the House of Commons Justice Committee, Penelope Gibbs of Transform Justice said on its blog (A Magistracy in Crisis):

The Justice Committee does not use the word crisis in its new report on the magistracy, but they are definitely alarmed. They say morale is low, training is under-funded and inadequate, and magistrates have not been consulted on major changes effecting them. They point out that magistrates are insufficiently diverse, and that the recruitment process is poor.

Gibbs notes, among other things, that the report recommends increasing magistrates’ sentencing powers – from the current maximum of six months’ imprisonment to 12 months, under legislation passed but never implemented (see section 154 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003). It seems part of the justification for this would be to signal greater trust in the lay justices’ decision-making powers and thus boost morale. Numbers of lay justices have fallen dramatically in recent years, for a variety of reasons, though one of them is certainly low morale: see the Guardian report, by Owen Bowcott, MPs recommend extension of magistrates’ powers.

Gibbs, herself a former magistrate, was one of those consulted by the Justice Committee. Evidence was also taken from the Standing Committee on Youth Justice and the Magistrates Association, as well as the Prison Reform Trust, and various representative members of the magistracy itself. The MOJ and CPS gave evidence. But one of the surprising things about the list in the back of the committee’s report is the absence of the representative bodies of practitioners. No sign of the Bar Council or Law Society, let alone the Criminal Bar Association or the Criminal Law Solicitors Association.Given that one of the purposes of the report was to “consider whether the role of magistrates should be expanded”, surely those who routinely practice in their courts should have been consulted?

European Union

Tusk talk

Tusk talk

Former PM of Poland, now President of the European Council, Donald Tusk gave a speech to mark the 20th anniversary of the European Policy Centre, on 13 October. He warned against those forces aiming to destroy the liberal, tolerant and fair values of European democracy on which the EU was founded, with their appeal to “national egoisms” and the right of the stronger to dictate conditions for the weaker. Europe needed to be stronger in defending its values in the face of recent crises over migration and the Eurozone, and not fall into a fatalistic inertia. He cited Brexit as an example of the destructive trend, and said no one would ultimately benefit from it.

In fact, the words uttered by one of the leading campaigners for Brexit and proponents of the “cake philosophy” was pure illusion: that one can have the EU cake and eat it too. To all who believe in it, I propose a simple experiment. Buy a cake, eat it, and see if it is still there on the plate.

The brutal truth is that Brexit will be a loss for all of us. There will be no cakes on the table. For anyone. There will be only salt and vinegar.

Meanwhile, in court…

the Brexitigation hearing continued in the High Court. You can read the transcripts of argument here.

For commentary on this, and in particular on the question whether the case may have to be referred to the European Court of Justice, see:

Faisal Islam (Sky news), Brexit court case in the balance for Government who says:

What was thought of at first as a marginal case is now looking rather in the balance for the Government, with potentially huge significance for Brexit. […]

It is not impossible that the Supreme Court could refer the case to the European Court of Justice. This is one of the very same powers Gina Miller argues is being destroyed by Article 50.

This would appear to be the constitutional equivalent of breaking the space-time continuum.”

Jolyon Maugham QC (Waiting for Godot blog), Brexit: the important role of the Court of Justice, who points out that the previously (perhaps deliberately) hidden

question whether an Article 50 notification is reversible is a question of European law. And that has a striking consequence. Our courts may need to refer the matter to the Court of Justice of the European Union.”

Spinning Hugo Reversing Article 50, disagrees, suggesting that the claimant’s argument, that the government cannot without Parliamentary approval remove rights granted by Parliament, cannot depend on whether or not the notice under article 50 can be reversed.

If the claimant’s argument is correct then we would still require statutory authorisation even if the government could reverse itself. Reversibility cannot alter the answer. So, reversibility cannot be determinative, and so no referral to the Court of Justice is required.

See also:

- Mark Elliott, on Public Law for Everyone, On whether the Article 50 decision has already been taken

- David Allen Green blogging as Jack of Kent, Why the Article 50 case may be the most important constitutional case for a generation

- Adam Payne, on Business Insider, The legal case against enacting Brexit without parliament’s permission is much stronger than we thought

And finally, further impressions of the hearing from artists Isobel Williams, A remoaner at the RCJ Brexit hearing, day two, in which, attending the case on its second day (Monday this week, it eventually closed on Tuesday with judgment reserved), she vents her frustrations about the awkward view from the public gallery:

Below, you can see the bench, a confetti of highlighters in front of the Master of the Rolls, and a row of court staff, but in this classic piece of Victorian court design you – the public – can’t see anyone else, and that’s deliberate.

Then the Attorney General is on his feet, opening for the government.

The Master of the Rolls removes his wig for a couple of seconds and scratches his head. Don’t we all. He asks the AG a question. The AG answers. The Lord Chief Justice asks the AG the same question, rephrased.

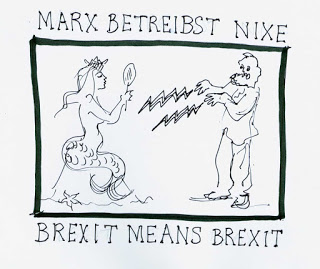

Her image is one of a series of teasing anagrams of “Brexit means Brexit”.

Great Repeal Bill

Could it be blocked in the Lords? That is the tantalising prospect offered by Lord (Norman) Fowler, whom some older readers may recall once served in a Conservative government. (He was the Minister for Transport who made seat belts compulsory.) He is currently the Lord Speaker. According to Politics Home:

Lord Fowler said the Great Repeal Bill, which did not form part of the Conservative manifesto, could be subject to the whim of the Lords.

“It will be just like any other piece of legislation,” he told the BBC’s Daily Politics.

“We’ll go through it and there will be proposals and then the Lords and the Commons can look at it and make amendments if amendments are necessary.

He refused to be drawn on whether the Lords could block Brexit legislation, but added: “As a general principle certainly I think the Lords at times can vote down something that has come from the Commons.”

And finally…

Legal publishing

At nearly 200 years old, Archbold must be one of the oldest continually updated legal textbook in England and Wales. The fictitious “Old Bailey hack” Horace Rumpole was fond of using it, albeit less for looking up points of law and practice, than for the sheer weight of its authority when dropped, noisily, to distract jurors from an awkward point emerging during his opponent’s cross-examination.

Archbold’s Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice (£475.00 at Wildy’s) is published by Sweet & Maxwell, which is part of Thomson Reuters, so you can read it online via Westlaw. However, Archbold’s longevity is no guarantee of its supremacy, and a recent survey of judges found a majority in favour of the rival publication, Blackstones Criminal Practice (£375.00). Which is published by the Oxford University Press, and is available online from Westlaw’s arch rival, LexisNexis.

Following the survey, the Judiciary Executive Board announced that Blackstones would be the standard text on the bench of Crown Court Judges from the end of this year. (See our earlier blog.) The editors of Archbold have responded in a manner described by one Judiciary insider as a case of “someone throwing their toys out of the pram”, with a preface to the 2017 edition that begins by expressing the editors’ “disappointment” at the JEB’s decision, and reminding readers that:

Archbold is a serious work for practitioners who are serious about the actual practice of criminal law. It is not a work that is aimed at students or beginners with little or no knowledge of criminal law and practice.”

The clear implication is that Blackstones is little better than a Criminal Practice for Dummies guide for amateurs. Oh dear. But of course there are other reasons for preferring the junior work. Many practitioners prefer it because it’s easier to use; and clearly the judges preferred it in that survey. On the other hand, the advantage of Archbold is that it routinely cites and links to the Criminal Appeal Reports, which the Lord Chief Justice has said in a practice direction ([2015] EWCA Crim 1567) should be cited in preference to any rival series apart from the Law Reports from ICLR.

Of course, from Rumpole’s point of view, none of this matters as much as how much the books weigh. And on that score, I think Archbold still comes out top.

That’s it for now. Our thanks to all who flagged up stories, via their blogs (which we always try to acknowledge) and via Twitter (where useful tweets are retweeted).

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content at ICLR, who also tweets as @maggotlaw. It does not necessarily represent the opinions of ICLR as an organisation. Comments welcome on Twitter @TheICLR.

Sign up now for weekly email alerts from this blog. Just put your email address into the box on the left.