Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR – 19 June 2015

This week’s collection of legal news and events includes more on Magna Carta, a legal triumph for Lego, a despatch on dubious dealings, and a survey of sickness and stress in the Civil Service. Plus more horrors from Abroad. And some nice pictures. You’re welcome. Magna Carta redux Universal law that anyone can cite Celebrating the

This week’s collection of legal news and events includes more on Magna Carta, a legal triumph for Lego, a despatch on dubious dealings, and a survey of sickness and stress in the Civil Service. Plus more horrors from Abroad. And some nice pictures. You’re welcome.

Magna Carta redux

Universal law that anyone can cite

Celebrating the 800th anniversary (or octocentenary) of the original sealing of Magna Carta by King John on 15 June 1215, by the banks of the Thames at Runnymede on Monday, the prime minister David Cameron, addressing the Great and the Good in this land, who had assembled in all their finery, wasted no time in citing the historic charter in support of his plans to sweep away the Human Rights Act 1998 and replace it with a British Bill of Rights saying much the same thing but in slightly different words (we expect). Some sense of what he planned to say could be gleaned from his editorial in The Sun the previous day:

I’m absolutely clear: we will scrap the Human Rights Act, and, with a new British Bill of Rights, we’ll restore common sense to our legal system. […] After all, it was this country that invented the whole idea of rights. 800 years ago, on this day, something extraordinary happened on the banks of the Thames… ” (Emphasis added, in surprise.)

Despite his shaky grasp on historical fact, Cameron was no doubt listened to with rapt politeness by Her Majesty the Queen, and the various bishops, dignitaries and politicians in attendance. But he knew he could get away with it. You see, Magna Carta is like that. Anyone can cite it anywhere and at any time in support of whatever they want to claim.

Court reporters have long been accustomed to hearing litigants in person claiming to be “free men” entitled (often uniquely entitled) to rely on the provisions of Magna Carta which you probably never knew about, which say they are not bound by the laws that govern ordinary mortals, but may roam free about the countryside, enjoying their birthright to graze their sheep on common land, water their ponies at the town pump, park their motorised conveyance on someone else’s forecourt, and prevent any obstruction to the sunlight adorning their Englishman’s home which is his castle. And so forth.

A good recent example was in 2012 when members of the Occupy movement were being evicted from St Paul’s churchyard, where they’d set up a “tent city” in a futile attempt to shame the commercial institutions based in the area for their part in the financial crisis, and a rather more successful (unintended perhaps) effect on the careers of two prominent churchmen (one canon, one dean) at the Cathedral.

According to a politely puzzled Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury MR, in City of London v Samede and others [2012] EWCA Civ 160, [2012] PTSR 1624, at para 30:

First, he [ie Paul Randle-Jolliffe, one of the protesters] challenged the judgment on the ground that it did not apply to him, as a ‘Magna Carta heir’. But that is a concept unknown to the law. He also says that his ‘Magna Carta rights’ would be breached by execution of the orders. But only chapters 1, 9 and 29 of Magna Carta (1297 version) survive. Chapter 29, with its requirement that the state proceeds according to the law, and its prohibition on the selling or delaying of justice, is seen by many as the historical foundation for the rule of law in England, but it has no bearing on the arguments in this case. Somewhat ironically, the other two chapters concern the rights of the Church and the City of London, and cannot help the defendants. Mr Randle-Jolliffe also invokes ‘constitutional and superior law issues’ which, he alleges, prevail over statutory, common law, and human rights law. Again that is simply wrong – at least in a court of law.

HT to David Allen Green, who cited this case in his piece in Foreign Policy, The Destructive Myth of Magna Carta.

Yet for all its dubious worth as a source of rights, Magna Carta’s future seems assured for now. The statute that confers genuine and enforceable rights which David Cameron sneeringly refers to as “Labour’s Human Rights Act” has a rather less certain future.The Labour party criticised Cameron for using the 800th anniversary of signing of Magna Carta to reignite row over Human Rights Act, according to the Telegraph. A tweet by Jack of Kent, highlighting the irony of the situation, was eventually retweeted 1215 times, a pleasing coincidence, though it’s probably been retweeted a few more times since Monday.

The government wants you to celebrate Magna Carta, which you cannot enforce in court, whilst it repeals the Human Rights Act, which you can.

— David Allen Green (@davidallengreen) June 14, 2015

Lego law

Brick court triumph

Lego, the well known construction toy maker, have successfully fended off the objections of a rival, the Lancashire-based toy maker Best-Lock, to the trade mark registration of their characteristic mini-figures as a protected shape. According to the Guardian, the Danish company registered its figures as a three-dimensional trademark in 2000 after protection under a technical patent registered in the 1970s came to an end. Best-Lock argued that the shape of Lego’s tiny men and women is determined by “the possibility of joining them to other interlocking building blocks for play purposes”.

Lego, the well known construction toy maker, have successfully fended off the objections of a rival, the Lancashire-based toy maker Best-Lock, to the trade mark registration of their characteristic mini-figures as a protected shape. According to the Guardian, the Danish company registered its figures as a three-dimensional trademark in 2000 after protection under a technical patent registered in the 1970s came to an end. Best-Lock argued that the shape of Lego’s tiny men and women is determined by “the possibility of joining them to other interlocking building blocks for play purposes”.

The case of Best-Lock (Europe) Ltd v Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) (Lego Juris A/S intervening) (Case T- 396/14) was decided by the first-instance General Court of the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg on 16 June.

If the court had agreed that the figures were mere building blocks, Lego’s trademark would have been invalid. But the court upheld Lego’s argument that its mini-figures are sufficiently distinctive in character to be more than just building bricks. It ruled that the toys’ characteristics, such as holes in the feet and a protrusion on their heads, did not obviously have a technical function. Accordingly they were entitled to claim protection.

Given this legal triumph, it is perhaps hardly surprising that Cambridge University has decided in its wisdom, or in response to a fat packet of funding, to appoint a chair of Lego studies. The Lego Professorship of Play in Education, Development and Learning will come with a research centre and £4m in donations from the Lego Foundation, reported ITV News.

To mark the company’s success in the European Court, I wonder if Lego should now produce a set of ECJ justices to match those apparently prepared (but never marketed) to celebrate the women justices in the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS), as depicted below. It may seem extravagant not only to insist on praising these unelected judges, as some critics like to call them, but also to pass them off as a parcel of blockheads. But you never know, they might make a very appropriate judicial toy.

Ad hominem

When is an ad not an ad?

When it’s posing as a blog or vlog, “reviewing” a commercial product which it is actually puffing for an (undisclosed) fee. Given the trust some people place in the apparently unmediated, unmoderated world of personal blogging to speak truth to commerce, it is worrying that there is no proper regulation of what might amount to advertising. This compares unfavourably to print media where rules about declaring “advertorial” content are more transparent. While the Advertising Standards Authority’s rules are clear that adverts must be clearly identified as such, many bloggers and brands are confused about what exactly counts as an advert.

The practice is now to be investigated by the Competition & Markets Authority, referred to as the UK’s “antitrust watchdog”, according to an article by Lindsay Fortado in the FT (Antitrust authority to investigate paid-for editorials, 19 June 2015).

* Incidentally, we have in the past republished “sponsored” posts from another blog, mentioning ICLR in a favourable light. I don’t think anyone was in any doubt that they were intended to perform a marketing function, despite being entertaining in themselves.

Flashy business

High Frequency Algorithmic Trading

The use of HFAT, alternatively HFT, seems to be growing and can be regarded as a legitimate way of turning a (very) fast buck on the stock markets. But it is notoriously prone to abuse, leading to “flash crashes” temporarily wiping billions off aggregate share values. Some institutions have exploited it to make undisclosed profits from deals at the expense of their OWN CLIENTS, which is frankly unethical, and lone traders can fraudulently manipulate the market to their own lucrative advantage.

Regulation of the markets is almost always at a disadvantage in that it struggles to catch up with the techniques developed for outwitting it, and is hampered by the powerful narcotic effect on politicians of business lobbying, especially by the financial services industry.

Discussing the regulation of HFAT sufficient detail to give it justice would take all day and almost certainly expose regrettable gaps in this writer’s knowledge; suffice it to say that the subject has been rather more comprehensively dealt with by two articles by Alex Hitchcock on Keep Calm Talk Law, here:

- Regulating High-Frequency Trading: The UK

- Regulating High-Frequency Trading: New EU Rules

- See also: Speed dealing: Flash Boys and the world of high frequency trading (review on this blog of Michael Lewis’s book on the subject)

Hey, hey, MOJ…

Unjoined up thinking rules (rues?) the day

The previous Lord Chancellor, Chris Grayling, was famous for wanting to achieve a “rehabilitation revolution”. He was also keen to make crime pay – not the criminals, nor the lawyers, but the justice system. Or at any rate for it not to cost anything. Ever. So he introduced a Criminal Courts Charge, according to which anyone convicted of an offence or pleading guilty in the Crown Court or before magistrates was obliged to pay to the court its costs for the privilege. The fees chargeable are listed according to a scale, from £150 to £1200.

In the Crown Court at Exeter this week, a judge questioned the wisdom of this approach, as he sentenced a shoplifter of no fixed abode to 15 weeks’ imprisonment and imposed, as he was obliged to do, a criminal courts charge of £900. According to the Express and Echo,

Judge Alan Large told [the defendant]: “I must impose the criminal courts charge in this case.” As he was led away he added: “He cannot afford to feed himself, so what are the prospects of him paying £900?”

When the prisoner was released, he would be subject to a debt which he had no obvious means of paying. The likelihood of his going straight and being able to repay the debt seems, if you think about it, slender at best. The only revolution likely to occur in his rehabilitation might be his turning around and going straight back into prison. But we can hope for a better outcome. After all, not even the MOJ has found a way to monetise hope.

This kind of contradiction seems to lie at the heart of much current government policy on crime and justice. The twin roles of Lord Chancellor (champion of the judiciary and the legal professions) and Secretary of State for Justice (unswerving implementer of government cuts and restructurings) already generate conflict. Then there are things like celebrating and endorsing Magna Carta with an exclusively high-priced event promoting commercial litigation while whilst pursuing policies in direct contravention to its spirit and intendment, such as imposing ever more stringent limitations, by cost and otherwise, on ordinary mortals resorting to the justice system to defend their rights. Or for that matter, how about cutting all legal aid fees to lawyers to the bone, calling them “fat cats” for daring to claim fees that might with a pinch exceed the minimum wage (but many do not), and then giving the civil servant in charge of legal aid a fat cat salary of nearly a quarter of a millions pounds? (see Guardian, Head of legal aid’s pay rise an ‘insult’ to solicitors after fees fall 17.5% in last year)

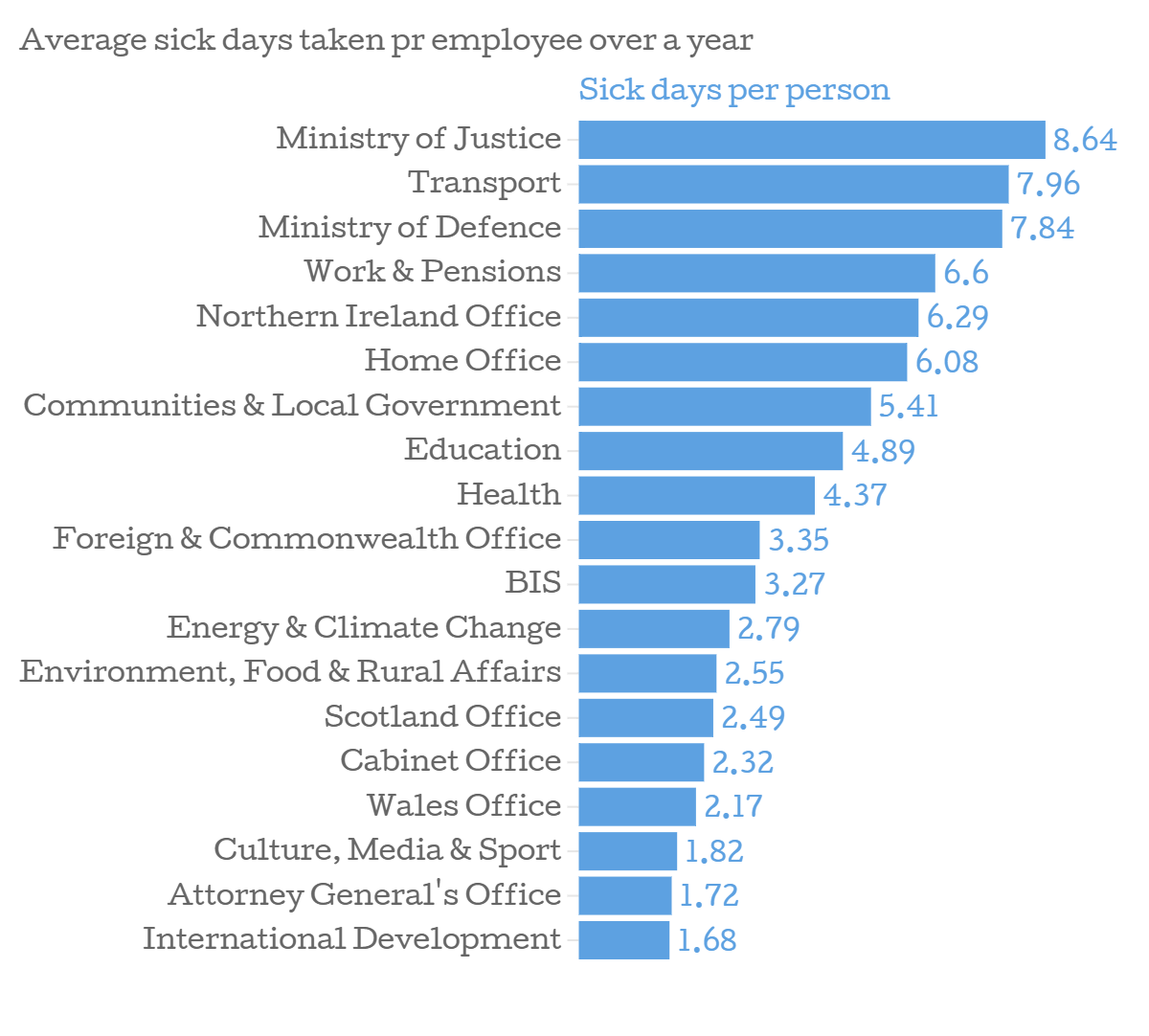

Stress bunnies

In the circumstances, it may not seem that surprising to learn that of all the government departments included in a survey of sick days taken on grounds including stress-related illness, the MOJ came top of the league table. (See City AM: Ministry of Justice is the sickest government department – and stress is the number one cause of time off among government employees)

At the MoJ, the total number of sick days taken over the 2013/2014 financial year was 601,237, spread between 69,575 staff at its central divisions. This amounted to an average of 8.6 days taken off per person. In its response, the MoJ said it was “working to bring down” days lost to sickness across the department.

Law (and injustice) around the world

Estonia

Website liable for comments

Unusually, the European Court of Human Rights (Grand Chamber) has held that an internet news portal website was liable for anonymous and allegedly defamatory comments from readers on its pages: Delfi AS v Estonia (Application no. 64569/09) judgment 16 June 2015. According to Ars Technica UK, citing Access, this goes against the European Union’s e-commerce directive, which supposedly guarantees liability protection for intermediaries that implement notice-and-takedown mechanisms on third-party comments (Directive 2000/31/EC).

In justifying its decision that the Estonian law did not infringe the applicants’ rights under article 10 (free speech), the ECtHR cited “the ‘extreme’ nature of the comments, which the court considered to amount to hate speech; the fact that they were published on a professionally-run and commercial news website,” as well as the “insufficient measures taken by Delfi to weed out the comments in question and the low likelihood of a prosecution of the users who posted the comments”; and the moderate sanction imposed on Delfi (paras 140 ff).

You can see some of the comments (translated into vigorous anglo saxon) in para 18 of the judgment. Suffice it to say the Nordic tradition of trollery is in rude health over there.

Iran

Lawyer arrested for shaking client’s hand

Last week (Weekly Notes – 12 June) we reported on the trial and sentence of Iranian cartoonist Atena Farghadani for her criticism of the government. Not content with sentencing her to nearly 13 years in prison for a few posts of Facebook and associating with families of political prisoners, the regime has now arrested her lawyer, Mohammad Moghimi, after he had shaken her hand in the course of a visit to his client in prison. You read that correctly: he has been charged with something or other for shaking her hand. He is now languishing in jail awaiting trial for an offence for which his client will now probably also face fresh charges.

Source: Global Voices

One wonders whether Iran is a signatory to the UN Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers. And if so, whether that would really deter them anyway. Article 16, among others, would seem to be relevant:

Governments shall ensure that lawyers (a) are able to perform all of their professional functions without intimidation, hindrance, harassment or improper interference; (b) are able to travel and to consult with their clients freely both within their own country and abroad; and (c) shall not suffer, or be threatened with, prosecution or administrative, economic or other sanctions for any action taken in accordance with recognized professional duties, standards and ethics.

Thanks to @Dragonblaze for referring me to this.

For more information on the application of these principles, see Lawyers for Lawyers

Kuwait

Six-year sentence for critical tweets

Kuwait’s Court of Cassation has upheld the six-year prison term imposed on Saleh al-Saeed, a blogger, for a series of tweets he posted criticising Saudi Arabia. According to Human Rights Watch, Hani Hussain, al-Saeed’s lawyer, said that Kuwaiti authorities charged al-Saeed after the Saudi embassy in Kuwait City had complained to the Foreign Affairs Ministry and demanded his prosecution. On December 30, a court of first instance convicted al-Saeed under article 4 of the country’s 1970 National Security Law, which makes it a criminal offence to commit a hostile act against a foreign country that disrupts Kuwait’s political relations with that country or exposes Kuwait to a risk of war. Since December 2014, Kuwaiti authorities have charged at least five other people with insulting Saudi Arabia or its ruling family.

That’s it for now. (Check for updates in the next day or two.) Enjoy the week ahead, and don’t forget to vote in our 150 Years of Case Law on Trial poll, now on its final stretch, 1996 to 2014.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content at ICLR. It does not necessarily represent any views of ICLR as an organisation.