Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR — 28 January 2019

This week’s roundup of legal news and comment includes mental capacity law, domestic abuse legislation, cohabitation and the myth of the common law marriage, and developments in legal information and ethics. But first, the work-life balance for lawyers and how it can be improved.

Legal Professions

Work-life balance — can law tech promote diversity?

A couple of things here. A report, Back to the Bar, by the Western Circuit Women’s Forum, reveals that

- Almost two thirds of those who left the Bar on the Western Circuit over a six year period were women. Almost all of the men who left became judges or retired. The vast majority of the women who left did not become judges or retire, but apparently left mid-career.

- Most of the women who left cited the difficulty of balancing work and family commitments as a factor in their decision.

- A significant proportion of women who leave the Bar could be retained with changes to working patterns and culture.

- Inflexibility in working patterns necessitates expensive flexible or full-time childcare. Inflexibility in working patterns is seen as primarily due to traditional clerking practices and court listing procedures.

- Many working mothers seek part-time work, shorter trials or not to stay away from home which is seen to limit career development opportunities.

The WCWF report was compiled to examine what could be done to reduce the number of women professionals leaving and to increase the opportunities for those returning after taking breaks from work to care for children. It makes a number of recommendations, both for the way chambers manage working patterns for women members, but also in terms of “raising awareness amongst regulatory bodies, the wider profession and the judiciary” and advocating for greater flexibility in court listing.

The problem it addresses is part of a wider issue, which is not only a problem in itself but also has knock-on effects in terms of diversity in the appointment of silks and, in turn, the judiciary.

“The overall pattern across the Bar for the last decade has been that men and women join the Bar in equal proportions, but more women than men leave mid-career, with the result that the senior ranks of the Bar remain overwhelmingly male.”

That accords with Bar Council figures cited by Sir Geoffrey Vos, Chancellor of the High Court, in a recent speech entitled ‘Judicial diversity and LawTech: Do we need to change the way we litigate business and property disputes?’ Speaking to the Chancery Bar Association’s annual conference on 18 January 2019, he said that

“It is pretty obvious that the diversity gap in the senior judiciary is, at least partly, because the pool of solicitors and barristers from which senior judges are selected is itself inadequately diverse.”

He notes that while only a third of barristers with 15 or more years’ practice are women, the number in the chancery and commercial Bar dops to a fifth, with only 11% for QCs. “In my view,” he says, “the way we actually resolve Business and Property litigation has a lot to answer for.” The problem, he explains, is that:

“To achieve real success in a litigation practice, we seem to require our lawyers at all levels to dedicate so much of their time to their professional activities, that there is inadequate time for a proper life.

Many people are simply not willing to countenance the levels of commitment required to sustain a successful practice. I am talking about the sheer number of hours worked, and the requirement often to be available 24/7 and at weekends.”

To secure appointment as QC, candidates are required to “demonstrate achievements that can only be attained by working absurdly long hours.” As a result, women lawyers are put off applying and

“We are missing out on a whole cohort of talented women, and some men too, with caring responsibilities, or who cannot or do not wish to devote all their time to their work.”

There are similar but subtly different reasons why the pressures of litigation practice act as a disincentive to black and minority ethnic lawyers, who represent only 13% of barristers and only 8% of QCs. In consequence, he says, the most talented BAME candidates are not coming through in sufficient numbers to the senior judiciary.

The solution, he thinks, may lie in technology and the digital court development.

“What if we were able to devise a litigation system that did not make so many of the demands that the present system imposes on its lawyer participants?

I can imagine a system where, with much of the preparation taking place asynchronously, lawyers can log on and work at times of day that suit them; and where the judge would make orders online, and the lawyers and parties would fulfil their obligations to the same, perhaps shorter, strict deadlines, but outside the confines of a formal hearing.”

Sceptics may detect yet another full-colour promo for Flexible Operating Hours. But, to be fair, this was always one of the supposed benefits of that much-maligned initiative. Although there is shortly to be a pilot in some family and civil courts, plans were dropped for any equivalent testing in the criminal courts after “listening carefully” to (vociferous and apparently convincing) representations by the criminal bar. If Vos C’s enthusiasm is sufficient for the idea, perhaps there should be a pilot on the Business and Property Courts, aka the Rolls Building.

But his vision of FOH is not that of the traditional physical court sitting out of hours to accommodate litigants who lead busy lives or have caring commitments, at the expense of lawyers and other court workers having to fit their own busy and caring lives around those other demands. Instead, it is of a bright-sunlit-uplandish sort of court system in which everyone logs on and participates whenever it’s convenient for them, asynchronously, like a Whatsapp convo or Slack channel chat. And why not? It would certainly avoid all the hassle of surge priced transport and long HM Court Security & Confiscation Service queues. Plus the diversity bonus:

“These technologically empowered dispute resolution approaches would allow lawyers to fulfil their family commitments and also litigate at the highest level. They would be potentially less dependent on the social environment of the courtroom, which might make it easier for the talented less-privileged entrant to the legal profession to get to the top.” …

“I have little doubt that, if we were to reform the way we litigate Business and Property disputes, we would have a good chance of attracting and retaining a more diverse cross-section of talented young people to the legal profession in general, and to become specialist barristers in particular.”

Meanwhile, the way we litigate family law disputes in the face of the current crisis (or “workload challenge”) in public law children cases is the subject of some rather vague words of encouragement in the First View from the President’s Chambers of Sir Andrew McFarlane, President of the Family Division, which was published last week, and given a fairly critical reading by family barrister Lucy Reed on her Pink Tape blog, in A view from the Coalface.

As to work-life balance, she notes that: “some judges consider it the norm … to sit up to and even after 6pm and advocates are simply expected to have childcare in place.” She points out that:

“whatever the President says about how it cannot be right that we go the extra mile as a matter of routine, advocates in some areas ARE expected to go the extra mile ALL THE TIME. And roundly criticised when they can’t keep it up.”

She ends with a plea to the President and the higher judiciary to take the necessary responsibility for managing down the pressures on the professionals in their courts:

“Please don’t leave it to those of us at the coalface to sort out amongst ourselves by asking the impossible of those higher up the chain who hold far greater power than we. Please don’t leave it to DFJs to sort out this impossible task — it’s like feeding the five thousand. Please don’t allow a situation to develop where professionals in one area feel unable to speak up and burnout or leave as a result.”

Family law

Common law marriage: myth-busted

“Almost half of people in England and Wales mistakenly believe that unmarried couples who live together have a common law marriage and enjoy the same rights as couples that are legally married.”

That’s according to this year’s British Social Attitudes Survey — carried out by The National Centre for Social Research in response to a question commissioned by the University of Exeter and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. The responses show that 47% are under the wrong impression that cohabiting couples form a common law marriage — a figure that remains largely unchanged over the last 14 years (47% in 2005) despite a significant increase in the number of cohabiting couples. It appears that people are significantly more likely to believe in common law marriage when children are involved. Commenting on the findings, Anne Barlow, Professor of Family Law and Policy at the University of Exeter said:

“it’s absolutely crucial that we raise awareness of the difference between cohabitation, civil partnership and marriage and any differences in rights that come with each.”

Nothing could be more timely, and better calculated to raise such awareness, than the publication on 22 January of the Transparency Project’s latest myth-busting guidance note, Common Law Marriage: the rights of unmarried couples and the myth of common law marriage. It explains where the mistaken belief may have come from, why it is wrong, and what the main differences are between the rights (mainly to do with property) of those couples (with or without children) who are cohabiting and those who are in a marriage or civil partnership.

Mental Capacity

Call for evidence on revision of MCA Code

The Ministry of Justice are inviting interested parties to provide feedback on how best to refine and improve the Code of Practice under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 to reflect current needs. The Code of Practice is a key document supporting the MCA with practical guidance.

The questions in the Online Survey have been split by each chapter of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 Code of Practice document. Respondents have the option to provide comments on as many of the sections as they wish. The deadline is 7 March 2019.

The Act itself is not under review, but in a 2017 report the Law Commission recommended that “deprivation of liberty safeguards” (DoLS) should be reformed, naming the new system the Liberty Protection Safeguards (LPS). The new LPS Code of Practice will complement and be an integral part of the revised part the MCA Code of Practice. The changes will be introduced by the Mental Capacity (Amendment) Bill.

NB. We have avoided using the abbreviation COP for the Code of Practice as that is also widely used for the Court of Protection, which was established under the 2005 Act in order to deal with cases concerning the welfare, treatment, and management of financial and other affairs of persons lacking capacity to do so.

Domestic abuse

Bill addresses various concerns

Last week the government finally unveiled its new Domestic Abuse Bill, alongside a response to its consultation on the matter. The consultation was launched by the Home Office and the Bill is being managed by them rather than, say, the Ministry of Justice. But in many ways it is a cross-departmental effort, which deals with a number of different aspects of domestic violence and abuse. (Read the full consultation response and draft bill.)

Of particular importance to family law proceedings is the long-awaited prohibition, in clause 50, against complainants of domestic abuse being cross-examined by the alleged perpetrators in court. Instead, the court will be able to appoint an advocate to do the cross-examination, ie to ask the complainant questions about their allegations in order to challenge their version of events and put questions that the alleged perpetrator would have asked had they been allowed to do so.

In the criminal courts, where cross-examination by a non-represented defendant is already prohibited (under the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999), certain vulnerable witnesses also receive automatic eligibility for “special measures” to protect them against the fear and distress of giving evidence. This is currently only available to complainants on a discretionary basis; the Bill proposes that automatic protection is introduced.

The Bill is important in other respects. It lays down a standard legal definition of domestic abuse. It sets up a new office of Domestic Abuse Commissioner and provides for the funding and staff to enable them and their advisory board to perform their various functions. There are new powers to deal with domestic abuse through the issuing of domestic abuse protection notices and orders (DAPN and DAPO), breach of which can be dealt with by criminal sanctions. There are a number of other matters dealt with, including the use of polygraph (lie-detector) tests for offenders, who have committed domestic abuse offences, before being released licence, to help assess the risks; provisions for housing of victims of domestic abuse; and an extension of the extra-territorial jurisdiction of UK courts to deal with offences of violence against women overseas.

The Bill is part of a wider agenda under which the government hopes to tackle the problem of domestic violence and abuse through raising public awareness and by encouraging a concerted effort by police, local government, health and education authorities, and other agencies. Legislation alone is not enough.

The Lord Chancellor, David Gauke MP commented on the Bill and the government’s policy on domestic abuse at the Women’s Aid Public Policy Conference on Domestic Abuse on 23 January.

Further reading:

Transparency Project: Government publishes draft Domestic Abuse Bill and The New Domestic Abuse Bill: Enough Change for Victims in the Family Court?

DB Family law: A draft domestic abuse bill and Open justice and domestic abuse court hearings: now and under the bill

Law and Technology

Ethics and Algorithms

The Law Society Technology and the Law Policy Commission is holding four public sessions to take oral evidence from experts on the topic of algorithms in the justice system. The next session will be held at the Law Society in Cardiff on 7 February and the one after that will be held at the Law Society in London on 14 February. Both sessions will examine the use of algorithms in the justice system in England and Wales and consider what controls, if any, are needed to protect human rights and instil trust in the justice system.

The chair of the Law Society’s commission is Law Society president Christina Blacklaws, who also addressed some of these issues when chairing a panel on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the administration of justice at last month’s first International Online Courts Forum: see Online Justice: a global perspective.

See also, Law Society: Can algorithms ever be fair?

The Law Society’s investigation is being supported by the overall regulator, the Legal Services Board (LSB), which as part of its current business plan has launched a Technology Project to support the front line regulators in developing their own approaches to technology regulation. According to the LSB announcement:

“New technological innovations, including artificial intelligence applications like algorithmic decision-making, automated document assembly, chatbots as well as other developments like blockchain, have the potential to transform how legal services are provided, including making them more accessible and cheaper for consumers, but they also create risks for consumers and providers.”

The ethics of automated decision-making in a more general sense have been considered for the first time in a Europe-wide context by Algorithm Watch, who published a report on 25 January: Automating society – Taking stock of automated decision-making in the EU. Introducing the report, they say:

“Systems for automated decision-making or decision support (ADM) are on the rise in EU countries: Profiling job applicants based on their personal emails in Finland, allocating treatment for patients in the public health system in Italy, sorting the unemployed in Poland, automatically identifying children vulnerable to neglect in Denmark, detecting welfare fraud in the Netherlands, credit scoring systems in many EU countries – the range of applications has broadened to almost all aspects of daily life.

This begs a lot of questions: Do we need new laws? Do we need new oversight institutions? Who do we fund to develop answers to the challenges ahead? Where should we invest? How do we enable citizens – patients, employees, consumers – to deal with this?

For the report “Automating Society – Taking Stock of Automated Decision-Making in the EU”, our experts have looked at the situation at the EU level but also in 12 Member States: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands Poland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the UK. We assessed not only the political discussions and initiatives in these countries but also present a section “ADM in Action” for all states, listing examples of automated decision-making already in use.”

Legal information

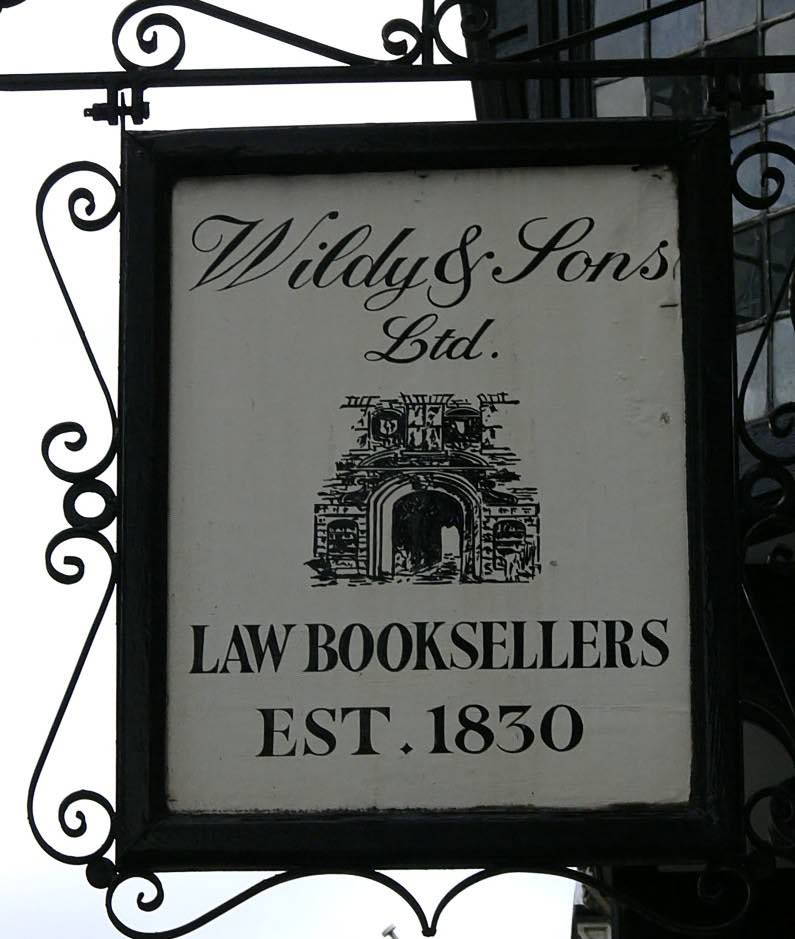

Wildy’s acquire Hammicks

Wildy’s acquire Hammicks

Wildy & Sons, the famous London law bookshop established in 1830, announced today that they have acquired Hammicks Legal Information Services, their main rival in the supply of law books, law reports (such as those published by ICLR), journals and other subscription services, to customers around the world. One of Hammicks’ main customers is the Ministry of Justice, who supply the judiciary and the courts.

Wildy’s have consistently scored highly in the annual British and Irish Association of Law Librarians customer satisfaction surveys. Their representatives often attend the same conferences as ICLR, with adjacent or even a shared stand in the exhibitors’ hall. We know them well and love them dearly, so our congratulations on their success is warm and heartfelt.

ICLR News

We continue the development of the Knowledge section on our website, with new content being added each week. The latest items added to our growing glossary of legal terms is an entry on Acronyms and initialisms in legal writing and another debunking the myth of Common law marriage (citing the Transparency Project’s latest guidance — see above).

And finally…

Tweet of the Week

A reminder of what pupillage is really all about, perhaps?

I try to offer colleagues coffee when I slip out of Chambers, @pret, and you have plenty of nearby branches, but I didn’t know you were hiring members of our profession to make the drinks. Can you or @CityWestminster shed any light on this? #membersofthecoffeebar pic.twitter.com/hNyprgqfM9

— Julien Foster (@childrenlawyer) January 25, 2019

That’s it for this week! Thanks for reading. Watch this space for updates.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content. It does not necessarily represent the opinions of ICLR as an organisation.