Rillington Place — Psycho-Pathé News meets Dr Stranglelove

The BBC’s three-part dramatisation of the tale of one of Britain’s most notorious serial killers was creepily authentic in its characterisation and atmosphere, but the mini-series left more questions than answers, says Paul Magrath in this review. Here’s something a bit spooky. Some years ago, a friend of mine who lives in Notting Hill attempted to

The BBC’s three-part dramatisation of the tale of one of Britain’s most notorious serial killers was creepily authentic in its characterisation and atmosphere, but the mini-series left more questions than answers, says Paul Magrath in this review.

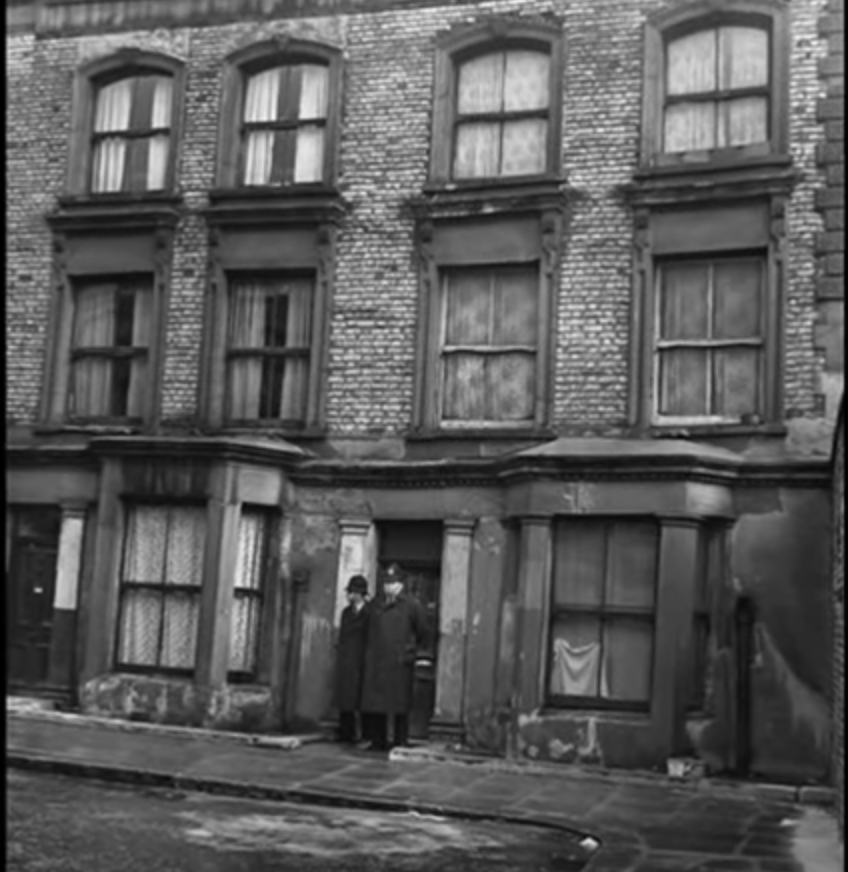

Here’s something a bit spooky. Some years ago, a friend of mine who lives in Notting Hill attempted to get a taxi home to her flat. The driver took her to the entrance to the road, but refused to go farther. “I’m not going in there, sorry love, I can drop you here and that’s it” was more or less how it went. She was not particularly happy about this, because it was late at night and the lighting was poor. But I now think the driver, for all his lack of chivalry (and breach of contract), might have had a reason. Or at any rate a superstition. For the road he refused to go down (Bartle Road) passes what was once one of London’s most infamous addresses: 10 Rillington Place.

The house, and indeed the whole of the short street of which it once formed part, was demolished in the early 1970s. The place where No 10 once stood is now a memorial garden, surrounded by a new development of houses and flats, Wesley Square, in one of which my friend lived. In other parts of Notting Hill the old Victorian houses have been restored and gentrified; but round here the buildings are all modern.

Rillington Place, in the BBC’s three-part drama series of that title, looked dismal and creepy. This is partly because your first sight of it comes during the Blitz, with fog and gloom to add to the wartime blackout and 1940s austerity. Even by day, everything seems washed out and faded to brown, as though the whole thing was shot in Sepiachrome, like an ancient Pathé newsreel. In the first of the three parts we are introduced to Christie, the villain of the piece, as seen from the perspective of his wife, Ethel.

Christie’s full name was John Reginald Halliday Christie, but he was known, via his second name, as “Reg” (so the only thing needed, when his case was listed for trial, would be the dividing “v” in “Reg v Christie”). At the time we meet him, he’s just being released from a short spell inside for an unspecified offence, which seems not to have precluded him from serving, in wartime, as a reserve policeman (complete with uniform). He and Ethel appear to have parted some years previously, but now he seeks her out again and they move to London. Their rooms in 10 Rillington Place are on the ground floor. The upstairs rooms are occupied by other tenants. As the longest serving tenant, Christie foists on all new inhabitants of the other rooms what he calls his “house rules” — relating in part to the use of the shared toilet and other common parts.

Christie is quietly spoken, though his quietness carries a menace, and he moves about with awkward deliberation. His part is played with a calculated creepiness by Tim Roth, in a role burdened by comparison with its earlier, legendary portrayal by Richard Attenborough in the 1971 film version. But the script is a new one and, as I have not seen the earlier film (only extracts), I shall say no more about it. What follows contains spoilers, but the story is historical so I see no reason not to tell it.

Before long Ethel starts to notice, or chooses not to notice, some odd goings on, such as Christie hammering away at something in the other room during the night, or gravely digging up the vegetable patch. She also chooses not to inquire too closely about unexplained stains on the bed mattress or the mysterious absence of an acquaintance whose coat has been left on the hook in the hall. On one occasion she sneaks out and follows Christie to a pub where she spots him consorting with a couple of tarts, but her complaint about it afterwards lacks conviction in the face of his brazen denials. And although she runs away to her family in Wales after a violent incident in the home — a salutary warning one would have thought — she eventually goes back to him meekly. After that you know she is lost.

A fatal injustice

In the next episode we learn the story of a young couple, Timothy Evans and his wife Beryl, who move into the rooms upstairs. Still struggling to cope with their first child, a daughter named Geraldine, they now have another on the way. Christie discreetly offers to help them solve the problem, stressing the attendant risks. (Posing as a reluctant backstreet abortionist seems to have been part of his modus operandi.) When Evans returns home, Beryl is dead and, convinced that it has all been a terrible accident of the illegal procedure, Evans assists Christie in disposing of the body and assents to him giving Geraldine to a childless couple to look after. Evans had a peculiarly low IQ, it seems, and went along with a plan that was to lead — after Christie and Ethel gave evidence against him at his trial for murder — to his being hanged. He was later pardoned, once the truth about Christie came out.

In the final episode, we find Christie finally letting go and abandoning himself to his perversions. He throttles Ethel with the air of one performing a long neglected chore and parks her corpse under the floorboards in the living room. He tells the neighbours she’s gone away, and in her absence they invite him to join them for Christmas dinner. He seems to do the normal-man-about-the-neighbourhood bit quite happily, and even jokes to a policeman, inquiring about the odd smell in his living room, that it must be on account of the funny cooking of the darkies who’ve moved into the upstairs rooms.

Later we see him bringing a succession of nervous looking women back to the kitchen, where he administers gas as though by way of anaesthetic, before throttling and sexually abusing them, and then hiding their corpses in and around the house. He keeps little tufts of their pubic hair in a secret box, and counts them like a miser. Though obviously a menace to society, he also seems no longer quite all there, frankly a bit dotty. When finally found and arrested, he comes quietly, almost relieved that the whole thing is over.

But why?

Christie murdered eight victims between 1943 and 1953. He may have murdered more, but these are the ones known about. This dramatisation of the last decade of his life suggests things without making them crystal clear. It shows his actions and something of his character, but does not really offer any explanation.

The way he kept the decaying bodies around him in his house finds a later echo in the serial killer Dennis Nilsen, who was a bit of a loner and would sit the corpses of his male victims in his living room, apparently for a bit of a chat of an evening, before popping them back under the floorboards. (See, for example, Killing for Company, by Brian Masters.) So I wondered if Christie did this too, or if he just muttered to himself about having Ethel right where he wanted her, firmly underfoot, or something. There is some suggestion he may have raped his victims after, rather than before, they were dead. But there’s nothing in the dramatisation to suggested he kept their corpses for this purpose.

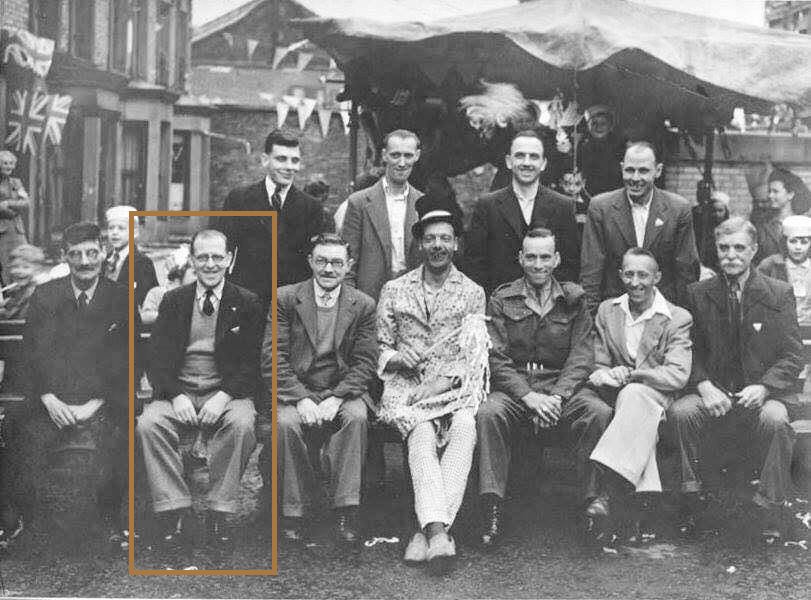

A different parallel may be found in the actions of the serial killer Fred West. Like Christie, he was considered a helpful, neighbourly sort of chap, with no one suspecting the darkness of his deeds till, all of a sudden, they were discovered. There’s a photograph of Christie at the VE Day street party in Rillington Place, looking like a respectable member of the community, just the sort of chap you might have running the local Neighbourhood Watch. It’s this dissembling look of normality that gives his murderous perversity an added depth of menace.

Reading around a bit, one can discover a certain amount to fill in the psychological background. It seems he had a problem with normal sexual relations owing to humiliation in an early (perhaps initial) sexual encounter and he seems to have had a problem with women and power ever after. He served in World War I and was gassed, a trauma to which his permanently quiet voice was later attributed. He was cunning and devious, planning his occasional acts of evil with premeditative care, assessing the risks of discovery and tidying up carefully after them, in a way that suggested he knew perfectly well what he was doing. At his trial, the defence attempted to rely on insanity (under the M‘Naghten rules then applying) but the jury were unimpressed, and he was convicted of murder.

Nevertheless, questions remain

Was he, if not insane, suffering some kind of psychosis or schizophrenia? There seems, surely, something of the Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in his respectable chap / killing machine dualism.

What happened in the early years of his marriage to Ethel, before they separated? Was it sexually satisfactory? Did simulated strangulation or playing dead form part of their coital kitty?

Why did they part and what was she doing during that interregnum? What was her motivation for supporting him, covering up for him? How much really did she know or suspect?

Were there ghosts at Rillington place? Are there still? (My friend never reported any, but one of these foggy midwinter nights might well be the best time to check!)

Legal subsequence

Two statutory landmarks of the 1960s may be said to have been prompted, at least in part, by events depicted in Rillington Place.

First, the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act 1965. The hanging of Timothy Evans was later exposed as a tragic miscarriage of justice. Such miscarriages were irreversible when the death penalty applied, though Evans was later officially pardoned, and his case was one of those cited by campaigners for final abolition.

Secondly, the Abortion Act 1967. The legalisation of abortion was prompted in great part by the dreadful risks faced by women desperately seeking a backstreet solution. Obviously Christie was only pretending to be such a practitioner, but many deaths ensued from complications attendant on even genuine attempts to bring it off. The age of shame gave way, in the 1960s, to a more permissive and forgiving age, and one of the dividends was the availability of safe, medically sanctioned and performed abortions.

Further reading / viewing:

BBC1: Rillington Place (Clips and series episodes on iPlayer).

Documentaries:

- Serial Killer John Christie: 10 Rillington Place (Crime Documentary)

- Murders That Shocked The Nation: Serial Killer John Reginald Christie Murdered Six Women

The original 1971 film was based on a book by Ludovic Kennedy, 10 Rillington Place (1961), which argued powerfully that Evans had suffered a miscarriage of justice. It is out of print.

There is also a novel by Ruth Rendell, Thirteen Steps Down, about a man obsessed by Christie and his crimes. (It was also made into a TV series on ITV.)

Paul Magrath is Head of Product Development and Online Content at ICLR.