Law in art: the judgement of Solomon

Depictions of the English legal system in art are rather less common than, say, its appearances in legal dramas or novels. This is surprising, given the opportunities it affords for the study of human nature in crisis. But one artist who has done justice to the subject is the 19th century British painter, Abraham Solomon. “Waiting for

Depictions of the English legal system in art are rather less common than, say, its appearances in legal dramas or novels. This is surprising, given the opportunities it affords for the study of human nature in crisis. But one artist who has done justice to the subject is the 19th century British painter, Abraham Solomon.

“Waiting for the Verdict” (1857) shows the family of the unseen accused waiting anxiously outside the courtroom while his barrister stands before the open doorway of the court awaiting news of the jury’s deliberations. You can see through the open doorway into the interior of the court, where a judge in red robes sits in an elevated, God-like position as other barristers confer or perhaps make submissions in the next case.

“Not Guilty (The Acquittal)” (1857) shows the relief and jubilation as the accused, released from the dock, is now reunited with his family, while his father congratulates the brief. One assumes any money passing hands will do so via the attorney (not shown) who instructed the barrister. Through an open doorway on the left you can see the light and air of the world outside. This vision of freedom mirrors the glimpse into the courtroom on the right side in the first painting, where the light appears to emanate from the no doubt distinguished and impartial judge, an idea reinforced by the painter’s surname.

The style is glutinously sentimental but that sort of thing was popular with the Victorians. (We must trust the judgement of Solomon, as it were, in knowing his market.) We know nothing about the offence charged, but the assumption is that Justice has been done and a Moral shown (trust the Law to defend the Truth).

It’s worth remembering that at the time there was no possibility of an appeal in criminal cases. In the absence of procedural complaint or reference on a point of law, the jury’s decision was final.

Now one puzzle remains. This pair of paintings, photographed in the Getty Center in Los Angeles, is said to have been the “Partial and promised gift of Barbara and Norman S Namerow”. Yet the same two paintings appear on the Tate website as part of its collection, “Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund and the Sue Hammerson Charitable Trust 1983”. One can only assume the images proved too popular to remain unique, and that the artist painted more than one copy. Or is one pair not quite as genuine as the other?

POSTSCRIPT

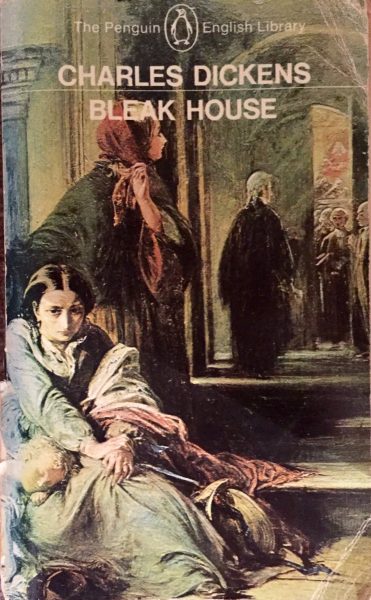

A portion of Waiting for the Verdict was used as a book cover illustration for the 1971 Penguin edition of Dickens, Bleak House (with thanks to Barbara Rich for tweeting it).