Constance Briscoe brought to book: a sad end to a promising legal career

The news that an experienced criminal barrister and part-time judge, Constance Briscoe, has been sentenced to 16 months in prison for three offences of perverting the course of justice has prompted widespread comment and, in some quarters, indignation. It brings a promising career to an abrupt end and, for a once inspiring role model, it is also a sad fall from grace.

Given the circumstances of the offences, and their connection to those of Chris Huhne and his ex-wife (Briscoe’s friend) Vicky Pryce, some comments have been directed to the apparent disparity in the very different sentences meted out to the three people for the same offence arising, initially, out of the same circumstances.

Briefly, back in 2003 Chris Huhne, one-time contender for the leadership of the Liberal Democrat party, persuaded his then wife, Vicky Pryce, to pretend she had been driving his car when it was detected to be illegally speeding. He did this because the points attracted by the offence would have lost him his driving licence, whereas if she “took the points” it would not have the same effect. When, subsequently, Huhne had an affair with his PR aide, Carina Trimmingham, he left Pryce and the family home. Hell having no fury, etc, Huhne paid the price for his duplicity when Vicky decided to confess her own in taking his speeding points. She went public (to a newspaper) and the story was picked up by the CPS who decided to prosecute the two of them. They were tried last year.

The case was subject of discussion over Pryce’s attempts to plead a defence of marital coercion (she was acting under her husband’s orders). The court ruled this out. See: Marital coercion: the ruling in R v Pryce.

Huhne, having failed to get the prosecution against him kicked out as an abuse of process, pleaded guilty. Pryce was convicted (eventually). Each was sentenced to 8 months in prison for the offence of perverting the course of justice.

This was the same offence that Briscoe was charged with. She faced three such charges. They related to witness statements taken by the police when investigating the Huhne/Pryce offences, in which Briscoe was alleged to have lied; and to her subsequent falsification of one of the statements. Briscoe told the police she had not had any contact with the press but in fact she had acted as an intermediary between Pryce, her friend, and the Mail on Sundy, to help spill the anti-Huhne beans.

She was convicted on 1 May 2014 on all three counts and the following day was sentenced to 16 months in prison. (See sentencing remarks of Mr Justice Jeremy Baker here.) This is twice what Huhne and Pryce got. But there were three counts; it involved lying to police and court and fabricating evidence; and moreover, she is a barrister and what the newspapers like to call a “top” judge (ie judge at any greater seniority than road traffic adjudicator). She is also black, and although this should make absolutely no difference, it has triggered what might be termed the “role model” factor: her triumph in making a success of her career so far is then turned into an aggravating factor in condemning her disgrace.

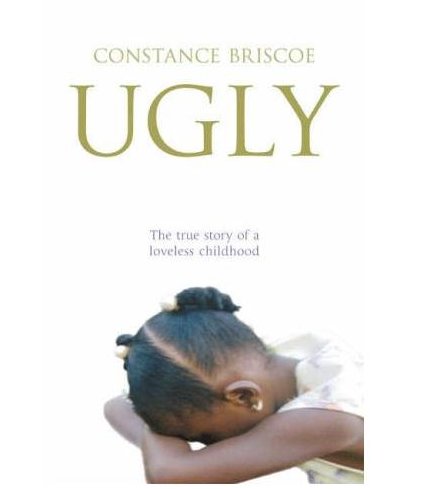

It is, at any rate, a spectacular fall from grace. I do not know whether Briscoe will appeal. (Her remark to the judge, after he had sentenced her, “I am grateful, my Lord” suggests a humble contrition, not the defiance of someone who thinks herself wronged.) She cannot rewrite history, although that is now what she is accused of having done already, in her memoir, Ugly, published in 2006, and reviewed by me in the printed predecessor to this blog. (I reproduce it below.) It was the subject of a libel action by her mother, who is blamed in the book for cruelty in her treatment of Constance (then called Clare). Her mother lost, but it is now being alleged that documents relied upon by Briscoe were obtained fraudulently.

Whichever way you look at it, her story, though triumphant in parts, is ultimately a sad one, even tragic. I found her sympathetic in my interview, and although much of the book follows the “misery memoir” formula, she has undoubtedly overcome significant obstacles and prejudice to get where she was, a successful barrister and judge, before her fall from grace. As a barrister, she cites Michael Mansfield as an early mentor. But as a writer, she was inspired by John Grisham. And it will be as a writer, I suspect, or possibly in TV, that she makes her inevitable comeback.

(I am indebted to Dan Bunting’s UK Criminal Law Blog for background facts used above.)

NB. The following article first appeared in 2006:

Ugly, by Constance Briscoe

Review and interview by Paul Magrath

Constance Briscoe is now a successful barrister and part-time judge. But for much of her schooldays Clare, as she was then known, was beaten, abused and bullied. Her chief tormentor was her own mother, a first generation Jamaican immigrant called Carmen, who when not pinching and twisting her daughter’s nipples, grabbing and squeezing what the author quaintly calls her “minnie”, belabouring her with a broken-off stair plank or kicking her in the stomach, was busy adding insults to all her injuries by calling her “ugly”, “scarface” and (for reasons that will become clear) “pissabed”.

The problem was that Clare, even in her early teens, was a chronic sufferer of nocturnal incontinence. She wet the bed. Her mother thought she did so deliberately, and would make her put her wet sheets back on the bed and sleep in them. Her GP recommended a special alarm, whose imperious clamour only exacerbated the problem. No effort seems to have been made to investigate the (fairly obvious) psychological cause. Yet as soon as Clare slept away from home, the problem stopped. And when she returned, it resumed.

The real problem, then, was her mother. But what was her mother’s problem? Perhaps it was her (ex) husband, another Jamaican immigrant, who after winning the pools had abandoned his wife and their growing brood of children, only turning up at Christmas time with food and presents. He was too busy landlording it over the little property empire he’d built up with his pools winnings to offer Clare more than occasional refuge from her mother and the equally violent stepfather, Eastman, who now occupied his place in the home.

You do not have to read too many newspapers, let alone law reports, to find plentiful instances of man’s or woman’s inhumanity even to their own offspring. But what distinguishes the author of this harrowing but somehow uplifting memoir is her indomitable spirit and her determination, from an early age, not only to surmount the various obstacles in her way, but to succeed in spite of them.

When attacked by her stepfather Eastman, for example, she goes to the local Magistrates’ Court and takes out a summons, as a result of which he is bound over to keep the peace, on pain of imprisonment. He keeps his own peace after that, but signally fails to keep that of Carmen, who later beats Clare so severely that she collapses at school and refuses to go home. A teacher, Miss Korchinskye, herself a refugee (from the concentration camps), offers to take her in. Fate punishes “Miss K” abysmally for this act of humanity: she is horrifically injured in an accident. But her kindness offers Clare a lifeline out of the hell of her domestic environment.

Another turning point comes with a school trip to the Crown Court. One of the barristers involved is Michael Mansfield, now a leading crime practitioner and campaigning, media-savvy silk. On hearing that Clare, a schoolgirl in her early teens, wants to be a barrister, he not only pays her the compliment of taking her seriously but even promises her a pupillage.

Despite every discouragement from home and school, Clare passes her A-levels and gets into Newcastle University. Her mother makes one last attempt to bar her way to the Bar: asked to countersign her daughter’s university grant application form, she simply tears it up. Clare has to postpone her entry for a year and work as a nurse to make her own way. In 1982 she graduates in law and in 1983 is called to the Bar. She writes to Mansfield asking when she can start her pupillage. He writes back: “Dear Constance, Come as soon as you like.”

Mansfield thus emerges as a sort of fairy godfather who, with a wave of his wand, transforms the fortunes of this Cinderella heroine. Meeting him when she did was certainly a lucky break, but Constance Briscoe, tracked down to her chambers in Bell Yard, in the shadow of the vast and labyrinthine Royal Courts of Justice, is less sanguine about the chances of today’s young recruits to the Bar.

“The problem at the moment,” she says, “is that you can’t get pupillage. When I came to the Bar everyone who was qualified would find pupillage. Now you have to have a First or 2:1. For me it was an achievement to get a degree in the first place.”

I point out that things have got better in that at least pupils are now paid. Perhaps surprisingly, she disagrees: “I don’t think pupils should be paid. I do think if students come to the Bar they should show some sort of determination. It’s not a continuation of university.”

So, no moaning at the Bar, and no mollycoddling either. “I think there should be a level playing field. I would not expect any special favours because I was black or had had a hard time. The opportunity should be available to everyone.”

Her own children are now approaching university age. Her son, 18, is on his gap year, her daughter is 16. What had they made of the book? She explains that it was one the reasons why she decided, in her mid-40s, to return to the trauma of her childhood. “I felt the time was right to write about my life so they would understand my past and the reasons why they have never met my mother.”

Writing it was “not an enjoyable occasion” but now, she says, “I have not a single regret”. Her children are proud of her. Colleagues from both Bar and Bench have been first astonished at the revelations in the book (“Mine is not a background shared by many at the Bar”) and then supportive, as has been the reading public. The book flew to the top of the bestseller lists, and has hovered there for several months.

It has obviously struck a chord with many readers. Though calmly written, it is an angry book. It’s a book that makes you angry just to read it. A pretty damning indictment, as they say.

But to the legal mind, of course, an indictment is not a verdict. It’s an accusation, not a judgment. The rules of natural justice demand that the other party be heard.

And so, perhaps, she shall. For Carmen has instructed lawyers of her own and is now threatening to sue. Constance Briscoe stands by her account and has the scars to prove it. “I am quite looking forward to the court case,” she says. “I might finally hear what it was that motivated my mother all those years.”

In the meantime, she has been writing more books. She was inspired to take up writing by meeting the legal thriller writer John Grisham (at Middle Temple Hall for the launch of his book The King of Torts), so it’s no surprise to learn that she has now written a crime novel of her own. A children’s story and further instalments of her autobiography are also waiting in the wings.

But she is not abandoning the law: she is keen to take silk and would welcome the offer of full time judging. Asked in which division she would like to sit, she is unhesitating in her reply: “Family”. Well, no one could say she had not the experience for it.