BVL: Model Law Commission Report 2022

We review the educational charity’s latest report in which embryonic law students investigate and propose law reform on various topics.

… Continue reading

Should children of 16 be allowed to write a will? Should they learn about NFTs and cryptoassets at school? Should they learn more about cybercrime?

These are just some of the questions asked and answered by the young people from non-fee paying schools who, thanks to the social mobility charity BVL, have immersed themselves in a particular area of the law, researched an issue that needs reform, and suggested what might be done about it. Not all the answers would perhaps survive the scrutiny of the parliamentary lawmaking process, but they should certainly provoke debate.

BVL – ten years on

The Model Law Commission is one of the activities by which BVL aims to inspire sixth formers from less advantaged backgrounds to prepare for a career in the law. Since its inception in 2013, BVL has enabled over 700 students to learn about the law and devise their own ideas about how it should be shaped.

Some of their proposals have turned out to be prescient, anticipating actual legislation later enacted by Parliament. In her foreword, BVL’s chief executive Victoria Anderson cites by way of example the criminalising of revenge porn, recommended by BVL students in 2014, which was enacted the following year in section 33 of the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015.

Many of the students from the scheme have gone on to graduate from excellent universities and qualified as solicitors and barristers. BVL stands for Big Voice London but in recent years, by moving online, the charity has expanded its reach to students across the rest of the country.

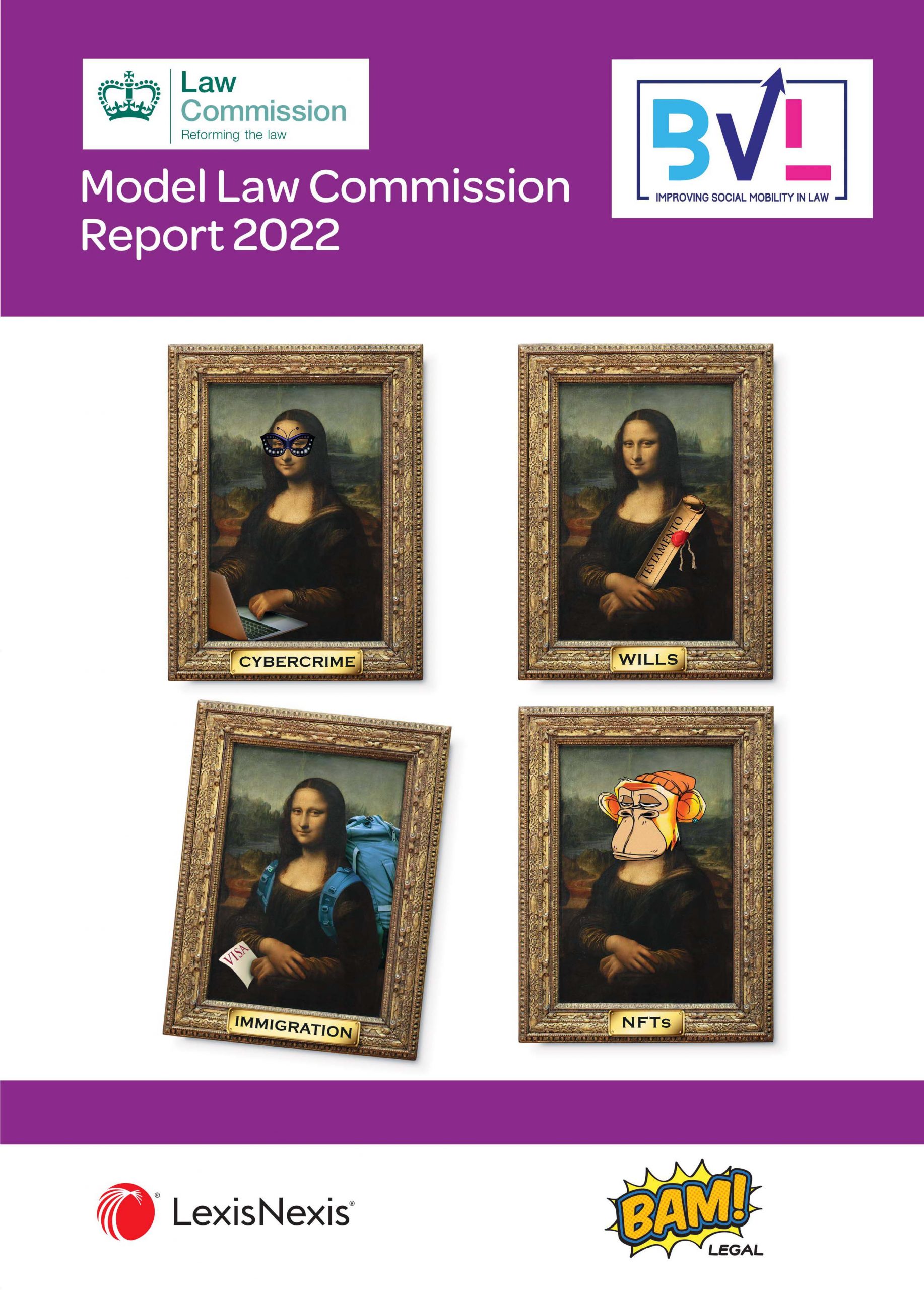

As in previous years, the witty cover artwork has been done by Isobel Williams, working with graphic designer Peter Sloper.

The report

The students are divided into four groups to tackle different areas of the law, and their research findings and proposals are then published under one of four headings.

Under Property, Family and Trusts, the team looked at the law relating to wills and intestacy. One of their proposals was to lower the minimum age at which a person can validly write a will from 18 to 16, subject to their having sufficient mental capacity to do so. As to testamentary capacity, they recommended adopting the test of a person’s ability to make decisions for themselves, under section 2 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, rather than the common law test in Banks v Goodfellow (1870) LR 5 QB 549.

The students also recommended that unmarried and same-sex couples should have greater protection under intestacy rules, to enable cohabiting partners to be provided for in the event that one of them dies without making a will. In particular, it is said, the surviving partner should have a share of any assets acquired during the cohabitation period, regardless of the formal status of ownership, provided they have been together at least five years.

Finally, under this section, and perhaps surprisingly, the team recommend abolishing what they call “the UK’s least fair tax”, IHT or inheritance tax. They point out that the deceased will already have paid taxes on most of what they pass on to their beneficiaries, and that it is a penalty on thrift and a burden on the bereaved, yet easily avoided by those genuinely wealthy enough to afford it.

Under Commercial and Common Law, the team focused on NFTs or non-fungible tokens, which they define as “digital assets that represent real-world objects like art and music, which are unique and cannot be exchanged”. However, they can be bought and sold, and there are risks inherent in the way that happens, and problems around their creation and impact on the environment, that warrant more regulation and better education.

Unlike other crypto-assets, NFTs are not taken seriously by regulators. While the EU has drafted the Markets in Crypto-assets (MICA) Regulation to regulate other crypto-assets, this does not currently cover NFTs. While traders might be subject to money laundering and other regulation, there is no consumer protection for investors in NFTs.

The team suggests there should be more education about NFTs, in particular at school. Really? There must be more important things to focus on, I would have thought, such as basic education about personal finance, tax and pensions, for a start.

Without either regulation or education about NFTs, the public is at greater risk of being scammed and most of those interviewed by the team said they would not feel confident investing in NFTs. Given that “the execution and validation of NFTs require more energy than the entire country of Argentina on an annual basis”, we should perhaps question the assumption that they are either a good thing in themselves or worthy of promotion as a product.

I wonder to what extent the team dealing with NFTs and their supposed benefits to society collaborated or discussed any common ground with the team covering the Criminal Law, whose report covered the law relating to cybercrime. The risk of being scammed, and of hacking more generally, would probably benefit from more educational attention. But perhaps not all children are quite so innocent: according to the National Crime Agency’s cyber crime unit, there were “students as young as nine deploying distributed denial of service attacks from 2019 to 2020”.

The current law, including the Computer Misuse Act 1990, is badly out of date and in need of reform. Moreover, the current punishments are not acting as deterrents, and there is a lack of scope for defences around public interest or ethical hacking where that is an issue.

Finally, on the area of Public Law, the team looked at immigration law, and in particular the treatment of asylum seekers from different parts of the world. This is a hot topic, now, with both the government and the opposition staking their claims to credibility on their ability to solve the small boats crisis which receives so much (generally hostile) coverage in the press.

The team point out that the UK has obligations under international law, notably the Refugee Convention of 1951, but in recent years has adopted a policy of creating a Hostile Environment for would-be immigrants and asylum seekers. While claiming to be concerned about human trafficking, the Home Office fails to provide support for the supposed victims of traffickers, insteaad making it harder to find a safe, legal route to claim asylum and demonising the “invasion” of “illegal” immigrants who arrive unofficially by boat.

The proposed reforms include making information more accessible for asylum seekers and the process of claiming asylum easier, for example by providing translation of the information and the application forms needed. A safe route could be provided using a visa system from France, rather than the current system of detention on arrival plus delay in processing claims thereafter (with the current backlog now topping 166,000 unresolved claims).

They also recommend that asylum seekers should be able to work pending the processing of their claims, thus better enabling them to support themselves than under the current system of minimal living allowances. The current 12-month wait before permission to work can be given should be reduced to six months. Finally the team condemns the “notable differences” in the schemes for Afghan and Ukrainian refugees and proposes that they be treated equally regardless of background.

As in the previous years, not all the recommendations will necessarily find favour, but the process of researching and discussing them will have been hugely beneficial to the students, and will hopefully inspire them in the study and practice of the law in adult life.

Featured image: NFT illustration via Shutterstock.