Book review: The Assault on Truth, by Peter Oborne

Paul Magrath gets ready to gasp and stretch his eyes as the veteran political commentator takes him on a guided tour of contemporary political mendacity.

… Continue reading

“His election as prime minister suggests that British people no longer care about the difference between fact and fiction, or truth and falsehood. What kind of a society have we become?”

This is quite an angry book. As a political commentator Peter Oborne has often expressed himself in trenchant terms, and this is not the first time he’s had to take leading politicians to task over their repeated and calculated mendacity. His earlier book, The Rise of Political Lying, was published back in 2005, when New Labour were still in power. One of its chapters was headed “The Lies, Falsehood, Deceits, Evasions and Artfulness of Tony Blair”. And before that he wrote a book about Alastair Campbell, New Labour’s notorious communications czar. So the fact that he’s devoted The Assault on Truth to the lies of Boris Johnson and Donald Trump, two populist demagogues on the right (who happened to be in the ascendant at the time of writing) merely emphasizes his objectivity.

If Oborne has a bias, it is towards what he sees as the traditional values of integrity in public office demonstrated in the past and largely absent, it would seem, today. He cites by way of example the ministerial resignation of John Profumo in a famous political sex scandal that shocked Britain in the early 1960s. (It wasn’t the sex that prompted his resignation, it was the fact that he lied to Parliament about the affair.) Profumo went on to redeem himself and earned the respect of his former colleagues. By ugly contrast, Oborne says he has “never encountered a British politician who lies and fabricates so regularly, so shamelessly and so systematically as Boris Johnson.”

This might not matter if Johnson were still a backbencher with a posh braying voice and a couple of day jobs in journalism (though even in that calling he often refused to allow the facts to spoil a good story). But he’s now running the country, with disastrous effects both on the rest of the cabinet (some of whom have adopted an equally elastic approach to truth-telling) and on the nation as a whole and its standing in the world.

Oborne quotes the Ministerial Code which insists: “It is of paramount importance that Ministers give accurate and truthful information to Parliament, correcting any inadvertent error at the earliest opportunity.” This is a matter of constitutional importance. The ability of Parliament to debate policy and for the government to be held accountable to the nation depends on ministers providing accurate information. The standard reference work on parliamentary conduct, Erskine May, warns members not to mislead the House: “Commons may treat the making of a deliberately misleading statement as a contempt.” But, says Oborne,

“Erskine May and the Ministerial Code are now ignored. Ministers (including the prime minister) lie and cheat with impunity. Their falsehoods remain contemptuously uncorrected on the official Hansard record. That is why I felt compelled to write this book: to attempt to explain the destruction and collapse of the twentieth century code of public integrity.”

Johnson and Trump v the truth

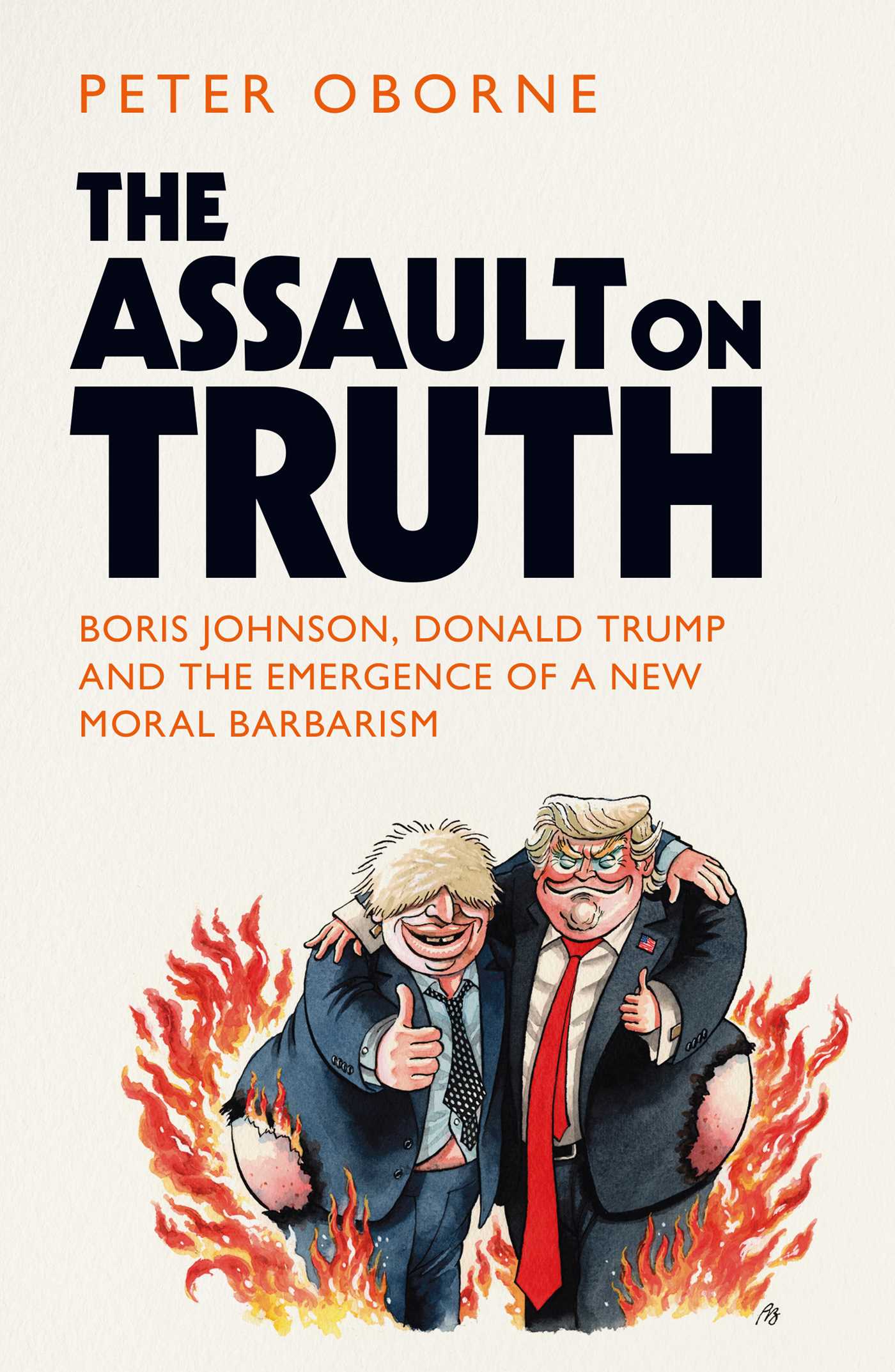

Superficially, the old Etonian Boris Johnson and the brash property tycoon Donald Trump, the other main subject of this book, could not be more different. But as attention-seeking populist leaders they lie in much the same way. While leaders on the left like Bill Clinton and Tony Blair “thought their lies were justified because they were in a good cause”, says Oborne, in the case of Johnson and Trump “they lie with humour and relish”, making up “outlandish claims which have little or no connection with reality”. They invent damaging falsehoods about their opponents and make promises they have no intention of keeping. As Trump’s “genteel country cousin”, Johnson is also Britain’s first “gonzo prime minister”. Both men are narcissists who put themselves at the heart of the story when campaigning and governing, and create a narrative of heroic competence around their own actions which rarely matches and often bluntly contradicts the facts.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in their response to the Coronavirus pandemic. Although never called the virus a hoax or promoted dangerously unsuitable treatments like Trump, Johnson and his ministers have systematically misled voters, repeatedly boasted about imaginary achievements and attempted to shift the blame to others when things went wrong.

Oborne sees this conduct as part of a wider pattern to dominate the narrative of government and discredit opposition, including the opposition or resistance of senior civil servants and the scrutiny of parliament and the press. The mainstream news media, in particular, have failed to check or challenge the lies of government, preferring to maintain their privileged access to undisclosed sources and No 10 briefings. In some respects, enthusiastically disseminating lies from the No 10 machine, they have behaved like “cheerleaders to the government”. Likewise, in the US, Trump has “routinely been able to call on media allies, above all Fox News, to twist the political agenda away from his own lies and against his political enemies.”

A wider decline

In Johnson’s case, Oborne’s criticism is laced with bitter disappointment in someone he has known and worked with for years. As editor of The Spectator, Johnson had hired Oborne as political commentator. In his day Johnson was “by some margin the most brilliant political journalist of his generation, with a talent that at times crossed over the line to genius”. But Johnson was sacked both by The Times (for making up a quote) and by the then leader of the Conservative Party, Michael Howard (for lying about an affair).

In his political career Johnson abandoned the traditional qualities of the Tory party for “a narcissism that mocked the style of straightforward, sober, self-effacing politics of the post-war era. He turned his back on the public domain and the ideas of duty, honour and obligation that defined it.” His conduct has mirrored a decline in politics more generally, says Oborne. “This means the fact that Boris Johnson made it into 10 Downing Street ultimately tells us much more about the rest of us than about him.” His lying is symptomatic of a more general malaise with British politics, and that is why we should be more concerned about it than the press and public seem to be.

Compared to a serious political leader like Angela Merkel, a scientist raised in what was then “a hardline communist state where words and actions had to be measured with intense care”, Johnson comes across as an entitled but dangerous buffoon, which Oborne describes as “playing Bertie Wooster while others pursue on his behalf the agenda of Roderick Spode”. (For those unfamiliar with PG Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster stories, the character of Spode was a satirical portrait of the British fascist leader, Sir Oswald Mosley. I assume the comparison is intended to be a comic exaggeration, though perhaps not a very big one.)

In common with other populist leaders, both Johnson and Trump misrepresent themselves as anti-establishment outsiders:

“Johnson often conducts himself as if he believes the Brexit referendum of June 2016 has given him a political legitimacy to trash British institutions like Parliament, the Supreme Court and the BBC. For both the prime minister and the president, truth has become a weapon which can be reshaped, cancelled or deployed according to the needs of the moment.”

They thrive in an atmosphere of polarised opinions, made worse by social media, in which “their supporters assume whatever they say is true, and whatever their opponents say is false”.

Fighting back

Oborne has a number of suggestions as to how readers can help turn back the tide. Parliament, he says, “must take lying seriously”. Copies of this book have been sent to the speakers of both Houses, in the hope of encouraging them to insist on corrections by ministers of any misleading statements. MPs and public servants are exhorted to do their bit as well, and not accept or condone ministerial mendacity. And among the other suggestions, constituents are asked to put pressure on their MPs to support the rule of law and oppose attacks on the judiciary. “It is time”, says Oborne, “to stand and fight for decency, tolerance, truth, and the freedom which comes with it.”

Whether people will respond to this rallying cry remains to be seen. The book is a bestseller but the only explicit attempt to call Johnson out for lying in Parliament itself has come from a Labour MP, Dawn Butler, whom the deputy speaker somewhat mildly reproached by suspending her for the rest of the day. Outside of Parliament his lying is widely attested to, and commented on, but nothing seems to change. He is almost transparently Machiavellian in his bending of the truth to his will, yet in spite of this it is the will of the people that supports him.

The Assault on Truth: Boris Johnson, Donald Trump and the Emergence of a New Moral Barbarism By Peter Oborne (Simon & Schuster, £12.99)

Main image: Pinocchio wooden toys, via Shutterstock.