Book review: Judge Walden – Call the Next Case by Peter Murphy

Open and shut cases: Paul Magrath reviews the latest collection of entertaining curiosities from the Resident Judge of Bermondsey Crown Court

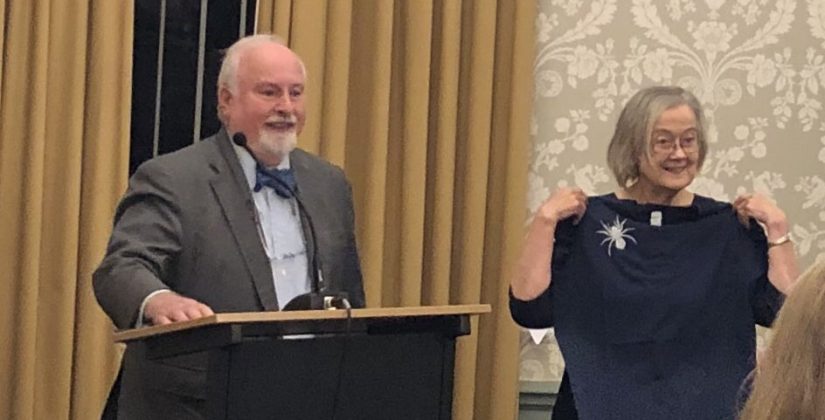

At a book launch held at the Law Society earlier this week, Peter Murphy, author of the Judge Walden series of Rumpolesque legal stories, gave Lady Hale the T-shirt her now famous spider brooch inspired.

Speaking at the launch, Lady Hale, who wrote the foreword in the latest volume of Walden stories, reminisced about the time she and Murphy spent studying law together at Cambridge. Though they have ended their careers in quite different judicial roles, the third speaker of the evening has perhaps had an even more unusual judicial career, though Strictly speaking Judge Rinder (who wrote the prologue in the new book) is not actually a member of the judiciary.

Call the next case

Charlie Walden, the resident judge of Bermondsey Crown Court, returns with another collection of curious cases, legal eccentrics, and bureaucratic battles with the Grey Smoothies from the Ministry of Justice, as recounted by author (himself a retired judge) Peter Murphy.

The cases are never quite as straightforward as counsel for the prosecution would like you to think they are. They recall that famous dictum of Megarry J, in John v Rees [1970] Ch 345, 402, on the subject of supposedly obvious cases:

“As everybody who has anything to do with the law well knows, the path of the law is strewn with examples of open and shut cases which, somehow, were not; of unanswerable charges which, in the event, were completely answered; of inexplicable conduct which was fully explained; of fixed and unalterable determinations that, by discussion, suffered a change.”

In one story, banished from his comfort zone, Judge Walden finds himself in the professionally anxious situation of trying a civil case about a property dispute in the High Court, while his own branch of the Crown Court, left in the charge of one of the other judges, is alarmingly besieged by rioting protesters.

In another, he consults his reverend wife, who happens to be the local vicar, on the theological niceties of polygamy, the subject of a criminal prosecution in his court. It makes for an awkward exchange in the marital kitchen:

“I’m interested in polygamy,” I begin.

She looks at me strangely and puts down her glass – though not the knife.

“What, after all these years, Charlie?” she asks plaintively. “I can’t believe it. After all this time I’m suddenly not enough for you? Who is she? Someone younger and prettier, I suppose…”

That case is also, in relation to a point of law, subjected to what Walden calls the “wanker test”. Without going into too much detail, it is in essence an objective standard of reasonableness which even the Man on the Clapham Omnibus might grasp. Other cases feature plausible fraudsters, a carve-up in a restaurant, and criminal responsibility for astrological predictions.

Although he is “beginning to feel like a relic of the past, a dinosaur in a post-meteor world”, Walden (or his creator) still has a finger firmly on the pulse of the criminal justice system of today – with all its current problems caused by spending cuts, CPS disclosure failures and the ominous prospects of court modernisation. As to the latter,

“Like Wilde’s cynics, the Grey Smoothies know the price of everything and the value of nothing: and sadly, I fear, by the time they have finished with us, there may be little left of a court system that was once the envy of the world.”

As fans of Walden’s earlier collections will recall, the rhythm of his day is marked out by the visit to the coffee shop where he picks up his morning latte, the break for lunch – “an oasis of calm in a desert of chaos” – and the agreeable evening meal consumed at home or in the equally homely local Indian or Italian restaurant, with his wife.

In the prologue, “Judge” Rinder describes Walden as defying description: “It’s like Rumpole meets Agatha Christie, with a bit of Judge John Deed thrown in – only with none of the absurdity.” The Rumpole comparison is also made in the foreword by Lady Hale, President of the Supreme Court, who was at Cambridge with Murphy in their undergraduate days. Rumpole is a natural comparator, and though the Old Bailey Hack himself would have categorised Walden as a “circus judge”, he would surely have respected him for the honest, unpretentious, and stubbornly conscientious avatar of justice that he is. We need more like Walden, and perhaps fewer of those devious Grey Smoothies.

Judge Walden: Call the Next Case (Walden of Bermondsey Book 3) by Peter Murphy (No Exit Press, £9.99).

See also Mr Justice Dingemans’s review of this book here.