Book review: Jeremy Hutchinson’s Case Histories

Jeremy Hutchinson, who later became Lord Hutchinson of Lullington QC, was a leading criminal defence advocate, involved in many of the most important cases of the 1960s and 70s, particularly those involving espionage, official secrecy and various forms of censorship. Paul Magrath reviews a celebration of Hutchinson’s most interesting cases, written up by fellow barrister

Jeremy Hutchinson, who later became Lord Hutchinson of Lullington QC, was a leading criminal defence advocate, involved in many of the most important cases of the 1960s and 70s, particularly those involving espionage, official secrecy and various forms of censorship. Paul Magrath reviews a celebration of Hutchinson’s most interesting cases, written up by fellow barrister Thomas Grant.

Let’s begin with ABC

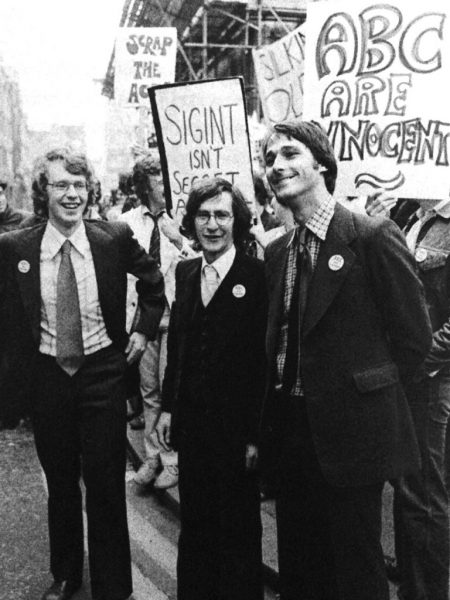

I first came across Jeremy Hutchinson when researching, as a student, an article on the Official Secrets Acts for the Bracton Law Journal [1]. My interest had been aroused by the then recent “ABC trial”, so called in part because the three defendants’ names began with A (Aubrey), B (Berry) and C (Campbell). Lord Hutchinson QC, as he had by then become, represented the biggest of these three hooked fish, Duncan Campbell, an investigative journalist who had managed to compile, from information in the public domain, a picture of Britain’s secret surveillance operations which ought to have been (and which the government ardently wished to remain) secret. Hutchinson’s junior was Geoffrey Robertson.

The case was something of a cause célèbre at the time. The government, through the agency of the Attorney General, Sam Silkin, had thrown the book at the defendants, particularly Hutchinson’s client, Duncan Campbell. All three defendants had been charged under section 2 of the Official Secrets Act 1911, the infamous “catch-all” provision outlawing the unauthorised disclosure of very broadly defined official information (basically covering anything the government didn’t want the public to know).

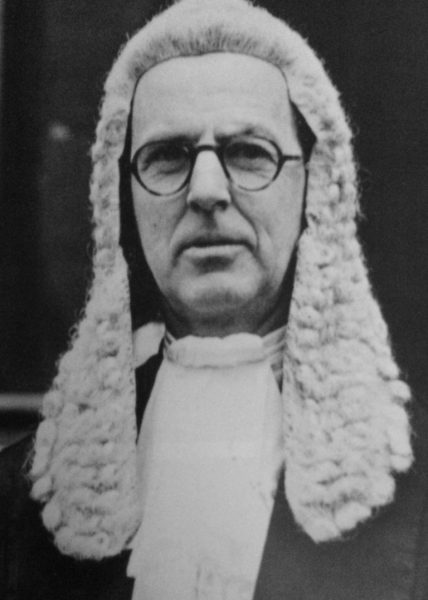

But charges has also been brought, far more seriously, under section 1, which was really aimed at espionage, rather than unauthorised disclosure. The 1911 Act had been passed at a time of rising panic over the risk of foreign agents snooping and gathering information which might be of use in enemy action. It had been a period of official paranoia, not unakin to that which now fosters enactments such as DRIP and the Investigatory Powers Bill. To charge two journalists and an ex-army officer on the basis of such draconian charges was excessive to say the least, and the trial judge, Sir William Mars-Jones, quite rightly insisted on the Crown providing proper justification for what he described as an “oppressive prosecution”. An additional charge under section 1 had been laid against Campbell, regarding his “collecting” of information which turned out to have been culled entirely from material already in the public domain. These charges were later abandoned.

Hutchinson’s conduct of the defence was fearless and robust, and his cross-examination of prosecution witnesses made a collective ass of the paranoid culture of official secrecy. He discovered, early on, that the jury had been vetted (by the Crown) and complained about this to the court. The fact that jury-vetting had been going on, routinely for certain types of trial, then became public. There were even supposedly guidelines about it (which were then grudgingly published). However, it later transpired that three of the jurors had signed the OSA (having worked for the government or in the armed forces) and the foreman of the jury was an ex-SAS man, which the Crown had somehow failed to disclose to the defence. The revelation of this rather significant fact led eventually (thanks to Christopher Hitchens blurting it out on TV) to the jury being discharged and the trial having to start again. Evidently the Crown when vetting the jury had not been concerned about possible bias against the defendants, only for their possible risk to national security.

Much of the fun of the case was derived from ludicrous circumstances such as the attempt by the Crown to conceal the location of well known defence establishments by assigning them numbers instead of using their real names, and to conceal the identity of some prosecution witnesses behind letters of the alphabet. The plan backfired spectacularly in the case of a mysterious “Colonel B”, whose identity (Col. HA Johnstone MBE, a former Signals commander) was soon discovered and revealed in various radical journals and also by several MPs in the House under cover of parliamentary privilege.

Although in the end neither Hutchinson nor the judge was able to prevent the charges under section 2 going before the jury or, given the circumstances, being found proven, the defendants walked out of court free men. Berry was given a short suspended sentence and the two journalists, Aubrey and Campbell, received conditional discharges. The whole case had been an expensive farce leaving the tight-lipped security establishment amply decorated with egg all over its face.

Secrets, spies, art and obscenity

The ABC trial was one of a number in the area of espionage and national security in which Hutchinson was involved in the course of a long and successful, in fact stellar, career at the Bar. He had earlier that decade defended Jonathan Aitken and the Sunday Telegraph in another case brought under the OSA, over a leaked report which demonstrated that the Labour government had misled the public over its covert support and arms shipments to Nigeria during the Biafran conflict. In the early 1960s he had defended six members of the Committee of 100 in another OSA case, in which the pacifist demonstrators were charged with “entering a prohibited place” namely an air base, for purposes (but this was the issue) “prejudicial to the safety or interests of the state”. In the same period he also represented the notorious genuine spies George Blake and John Vassall.

But it was not just in cases about spies and secrets that Jeremy Hutchinson excelled. There’s hardly a prominent trial over the three decades from the mid-1950s that he was not somehow involved in, as what Thomas Grant calls the “most sought-after criminal defence barrister at the English Bar”. Among his other clients, he appeared for Charlie Wilson, one of the Great Train Robbers; for the prolific art forger, Tom Keating; and for the society drug smuggler Howard Marks.

A particular area of expertise seems to have been cases under the Obscene Publications Act 1959, with Hutchinson appearing as defence counsel for Penguin Books over their publication of a cheap paperback edition of DH Lawrence’s novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover; for bookseller Ralph Gold over a cheap reissue by Mayflower Books of John Cleland’s bawdy confessional novel, Fanny Hill; for Christopher Kypreos, over his publication of Paul Ableman’s less than wholly scientific treatise, The Mouth and Oral Sex; for United Artists over the sexually explicit film Last Tango in Paris; and for the National Theatre over a scene of simulated sodomy in Howard Brenton’s play, The Romans in Britain.

It was not always for the avoidance of conviction that Hutchinson’s powers of persuasion were engaged: he would also be called upon, in cases where a guilty plea was inevitable, for the provision of a plea in mitigation. In such cases, his speech would be addressed not just to the judge, from whom leniency was pleaded, but also the court of public opinion, to help redress the blighted and one-sided perception of an individual like Christine Keeler (charged with perjury and conspiracy to pervert the course of justice in relation to the Profumo affair) or George Blake, who had already confessed to spying for the Soviets.

Background and legacy

Jeremy’s father, Jack Hutchinson had also been a barrister. Indeed, he had appeared for the first author to be charged under the Official Secrets Act 1911, Compton McKenzie, whose war memoirs had attracted a charge under section 2 (essentially for revealing material embarrassing to the intelligence services, for whom he’d worked during the Greek campaign in World War I). Jack had also appeared in an obscenity case involving DH Lawrence, over his depiction of pubic hairs in a painting for which an art gallery had been prosecuted. So in a sense Jeremy was born into the profession; and also, after Stowe School, Oxford and the Royal Navy, with connections to the Bloomsbury group, membership of the Labour party (for whom he once stood as a candidate) and marriage to a leading actress, Peggy Ashcroft, you could look on him as a member, albeit a very liberal and reforming one, of the Establishment (in its most amorphous sense).

Thomas Grant’s book is not a biography, though it contains a biographical sketch. As indicated by the title, Jeremy Hutchinson’ Case Histories, it is really a celebration of Hutchinson’s career, timed to coincide with his subject’s 100th birthday in 2015, which takes the form of a discussion, in satisfying but not obsessive detail, of 14 of his most interesting cases (chosen out of hundreds). You can read about most of them elsewhere, of course; but the story is told from Hutchinson’s perspective and while not centre-staging him in such a way as to skew the narrative, it aims to show how his conduct of the cases may have influenced the course of history. There is a danger of overstating this, however. The Profumo Affair may have fatally wounded the Macmillan government, but it was the affair itself rather than Christine Keeler’s case that hastened its demise. The acquittal of Penguin books may have ushered in the so-called sexual revolution of the 1960s, but it would probably have happened anyway. The Official Secrets Act, badly wounded as it was, continued to limp along after the ABC trial, securing the conviction of Sarah Tisdall in 1983, but failing to secure that of another civil servant, Clive Ponting, two years later; and after the Spycatcher fiasco in 1987 the security establishment decided to give it up as a bad deal and concentrate on confidentiality and other, more pliable remedies to protect itself from embarrassment and public scrutiny (though these, too, spectacularly failed in that case).

After retiring from work as an advocate, Hutchinson continued stoutly to defend the idea of being an advocate, for example in a House of Lords debate (cited by Grant) on the Courts and Legal Services Bill in 1990:

At the very basis of our freedom lies the knowledge that in the criminal courts, however unpopular your cause, however hopeless, however unlikely, however seemingly overwhelming the pressure of the state upon you is as an individual, you can obtain an independent, professionally dedicated advocate to undertake and argue your case and to argue it before a tribunal which is presided over by an equivalently independent judge. From then on the advocate must fearlessly promote by all proper and lawful means that person’s interest without regard to his own.”

At the time, he feared the legislation under discussion might have the effect of limiting access to justice. One wonders how he feels now about some of the more recent legislation that has gone far farther in that retrograde direction than anyone then could have imagined. As Grant observes in his preface:

The principle that a person charged with a crime is entitled to representation by an independent person of their choice, whose skills as an advocate and lawyer are of the highest order, is in jeopardy.”

This absorbing book is, among other things, a demonstration of the value and virtue of that principle.

[1] “Official Secrecy and the ABC Case” (1980) 13 Bracton Law Journal 88.

*The images used in this post were taken from the book.