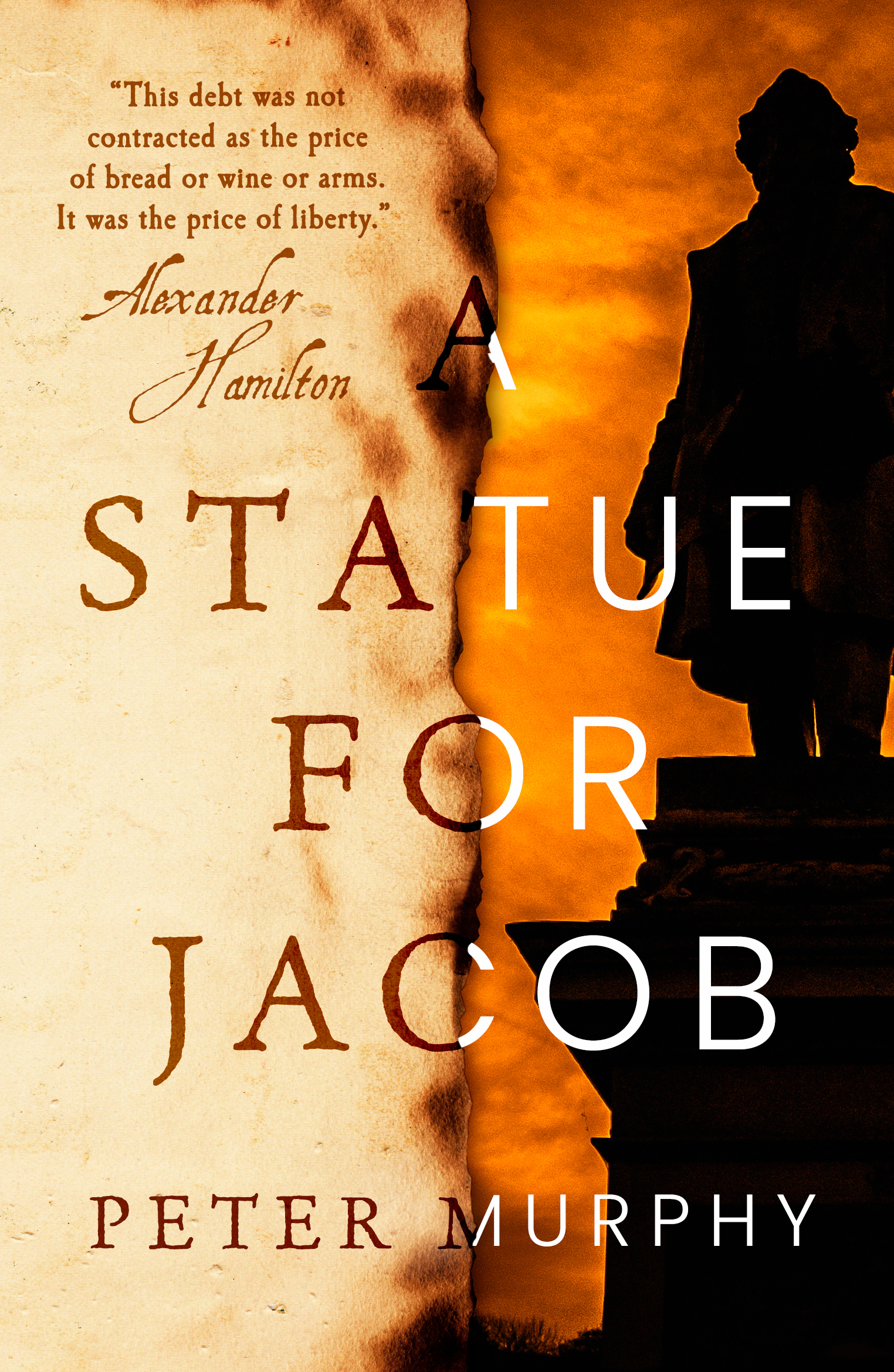

Book review: A Statue for Jacob by Peter Murphy

Paul Magrath reviews the latest novel from Peter Murphy, in which present day lawyers battle over a historical injustice dating from the American War of Independence.

Admirers of Peter Murphy’s thrillers about an English barrister and comedies about an English judge may be surprised by the change of direction in his latest book. Though still firmly based in the legal world and with many dramatic courtroom scenes, the whole story is set in the United States and stretches back in time to the War of American Independence.

The narrative style and tone also represents something of a departure from Murphy’s earlier work. It is much more emotional, romantic even, than the taut thrillers of the English courtroom and the sly wit of the judge’s memoirs. Nor is the story entirely fictional. In an author’s postscript Murphy reveals that the book is based on a real case that he was involved in, earlier in his career, when he lived and worked in America (teaching at South Texas College of Law).

The true basis of the story does not make it any less extraordinary or dramatic, though, for it involves nothing less than a family suing the Federal Government for billions of dollars in unrepaid war loans dating back more than two centuries to a time when the American states were fighting not just for independence but for their very survival.

To support their struggle to free themselves from the colonial yoke, the American troops needed money, which was raised by taking loans off patriotic wealthy supporters. Though the loans carried high risk, the intention was that they would be repaid after the war. And many of them were. But the loans made by one such patriot, Jacob van Eyck, during the winter of 1777-78, to help Washington’s army at Valley Forge, were never repaid and the loan notes presented for payment appear to have been lost or destroyed.

Without such documentary proof, the claims face a number of apparently insuperable challenges. The most obvious, to any lawyer reading this, is the statute of limitations. The claim is simply too old and long-delayed to pursue now.

There may be technical arguments to get round that obstacle (yes, even after two centuries), one of which is that a court having jurisdiction to deal with the case did not exist until nearly a century after the claims first arose. Even so, that would have allowed more than another century to make the claim. Another is the question whether evidence was deliberately concealed or destroyed by the government (as the intended defendant), which is naturally resistant to the idea of paying out billions of dollars in compound interest on the debt as well as the principal, and perhaps setting a precedent for other such historic claims.

There are also personal and emotional difficulties hindering the lawyer who takes on the claim, through whose eyes we see much of the story. Kiah Harmon is from an immigrant Indian family, and has her own battles to fight, after being dumped by her boyfriend, and her own solutions, in mystic healing and astrology. Other chapters are narrated from the point of view of the government lawyer handling the case against her. He’s a decent man working for officials higher up the chain of command who are not quite so decent and honorable.

When I say the story is told in a more emotional and romantic way than Murphy’s earlier work, I mean that there’s a lot of hugging and weeping and touchy-feely stuff which may be intended to offset the dry technicalities of the legal twists and turns. There’s even a strand of magic realism, in the early chapters, where Kia dreams certain scenes from the past, which may simply be a device to get those scenes into the book without having to present them in a more conventional split-time narrative.

Something that will certainly chime with many readers is the role played in the story by the historical figure of Alexander Hamilton, the subject of a contemporary hit musical. His writings and speeches dating from 1790, when he was Secretary of the Treasury, form part of the evidence and underpin an argument based on Article Six of the US Constitution. Hamilton is quoted as having declared, in relation to the repayment of the war debts, “This debt was not contracted as the price of bread or wine or arms. It was the price of liberty.”

If the debt cannot or will not be repaid, should the nation not at least recognise the role played by those, like Jacob, who supported that struggle for liberty? Hence the book’s title. The plaintiffs may be pursuing a claim in respect of a debt, but the remedy sought is one of recognition and acknowledgement, in the form of a statue of the hero whose debt cannot otherwise be repaid.

So will the government do the decent thing, and honour the people’s moral if not their financial debt? Or will they battle the claim as bitterly as they fought the Brits in that long cold winter of the battle of Valley Forge? As in history, the result seems perhaps less dramatic in retrospect than it must have felt at the time.

A Statue for Jacob, by Peter Murphy (Oldcastle Books, £9.99)

Featured image (top): Generals Washington and Lafayette at the battle of Valley Forge, in the winter of 1777-78, painted by John Ward Dunsmore (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)