Book and launch event: Litigants in Person in the Civil Justice system

Academics discuss important new research revealed in a new book on the experience of self-represented litigants in the civil courts… Continue reading

Last week a panel of academics discussed an important new book which depicts the experience of litigants in person in representing themselves in the civil courts of England & Wales.

The number of LIPs, as they are usually abbreviated, has risen steadily in recent years, against a background of legal aid cuts and economic pressures on many of the free advice centres. Though some choose to go it alone, most LIPs are forced to do so by lack of advice or representation. They face a system that is already struggling with backlogs and under-resourcing, and where they encounter barriers of language and culture, as well as suspicions and resistance from the lawyers for whom the system was primarily designed.

How do they feel about it?

For her new book, Litigants in Person in the Civil Justice system: In their own words, Dr Kate Leader decided to ask them. She conducted 15 oral history life-story interviews with LIPs who had initiated or defended claims in the county courts. The interviews generally took several hours and were not confined to the experience of litigation but also asked respondents about their pre-litigation lives and the effect on their lives after the litigation was over.

There has been a good deal of commentary from lawyers and academics about LIPs and their interaction with lawyers and the legal system in recent years, as well as regulatory and judicial guidance on how lawyers and judges should interact with and accommodate LIPs in a system not primarily designed for non-lawyers to navigate. But this appears to be the first sustained academic inquiry into how LIPs themselves feel about their experience. The author shines a light on how much we don’t know about LiPs, the civil justice system, and LiPs’ place within it, as well as the kinds of things we ought to be doing to improve access to justice for unrepresented parties.

The discussion

Leader is a Senior Lecturer in the Law department at Queen Mary, University of London, and it was there that, last week, that a panel of academics held a discussion about LIPs and their experience, as revealed in the book.

The event was introduced and chaired by Professor Naomi Creutzfeldt, of Kent University law school, and featured contributions from Professor Richard Moorhead, Exeter University; Dr Karen Nokes, UCL; and (appearing remotely) Professor Grainne McKeever, University of Ulster. The discussion was not just about the experience of the LIPs in the book but also about what were the underlying problems and what might be done to improve things. The following is a brief account of what they said.

Karen Nokes began by praising the book’s comprehensive analysis of LIPs and their experience and what stayed with them afterwards. She identified three areas of concern.

- Bad lawyers and lawyering. Access to justice couldn’t be guaranteed just by providing more lawyers, because often it was lawyers, or the way they gave advice and conducted cases, that caused the problem in the first place.

- However competent a person might be in their own or other areas of life, as litigants dealing with the law they often lacked the same confidence.

- Language and behaviour. These imposed barriers to those not versed in the legal system, with its formalities “take for granted” as much as its technicality.

Richard Moorhead said one only had to look at the experience of victims of the Post Office Scandal, such as Lee Castleton, to understand the wholly deserved sense of outrage felt by those dragged through a system which they had trusted to deliver justice. Very often they simply could not understand what they had been through. Falsely accused, suffering damage and loss: no wonder their mental health issues were often off the charts.

What was going to make people listen? The current guidance on how lawyers should deal with LIPs was pathetic and useless. But there might be a solution in providing a different kind of process, more like an ombudsman type procedure; unbundling of legal advice etc, to provide better access to justice.

Grainne McKeever said there were four types of barrier – intellectual, practical, emotional and attitudinal, that led LIPs to feel they were not welcome in the justice system. The disillusionment of those who thought they could trust in the British justice system was well illustrated by Lee Castleton’s hearing in the High Court.

Attitudes to LIPs ranged from the view that LIPs should be treated consistently, the same way as the lawyers; an acknowledgement that they were an inconvenience, but entitled to be there; to the view that their vulnerability should be recognised and accommodated by the system.

Leader responded and both she and the panellists took questions from the floor. From these it emerged that there was a role for public legal education (PLE) particularly to educate people as to what the legal process looked like, and perhaps for artificial intelligence, in the development of an automated procedure for helping litigants with small claims identify what those claims might be, and help them resolve them.

The book

There were, Leader told the meeting, “small pockets of hope”. This echoes what she says in introduction to the book, that “some of the difficulties described in this book administrative or minor and might easily be fixed, so we need to think about how we might do this”. At present, though, “for most LIPs, the experience of going to law if far worse than we have previously understood” leaving them with “a profoundly disillusioning effect on their trust in legal professionals and legal institutions”.

Before getting to their stories, Leader outlines what they are up against. In particular, the attitudes and assumptions of lawyers. That LIPs are risky or vexatious; that they cause problems for other court users; that they are a burden, and must be accommodated. They are DIY lawyers, according to one top KC, whose efforts at litigation are likely to be no more successful than someone performing DIY surgery on themselves.

I remember my pupil master telling me that “the lawyer who represents himself has a fool for a client”. This was obviously not a new observation, even then, since Leader quotes something from the County Courts Chronicle of 1866 wearily noting the “hackneyed observation” that “a man who is his own lawyer has not a Solomon for his client”.

The obvious solution might seem to be to provide more actual lawyers, and the lack of them is blamed mainly on the cuts to legal aid and other austerity measures. But that is because the modern courts have been designed for lawyers, not litigants. Yet this was not always so: I was interested to read about the local courts of request or courts of conscience which preceded the modern county courts, where less formal procedures accommodated small civil claims by unrepresented litigants. These were swept away in a fit of reforming zeal, with the County Courts Act 1846. Thereafter, it seems, lawyers held sway and self-represented litigants were mocked in the County Court Chronicle and other publications (see above).

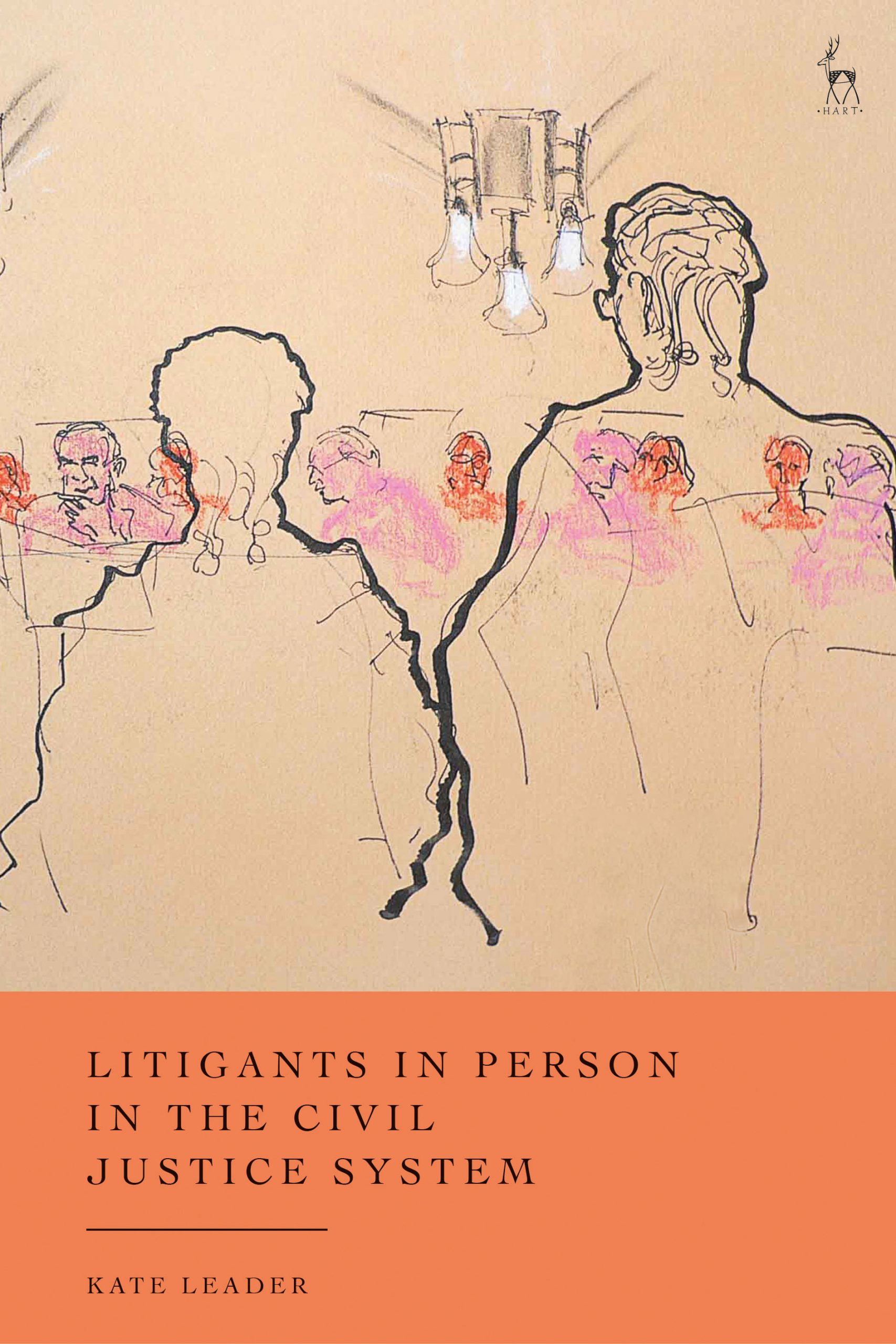

The litigants in person in this book come from a variety of backgrounds and with a variety of problems. In some cases they have had bad experiences with lawyers and become disillusioned or even paranoid about the “system”. Being a LIP only tends to enhance their sense of isolation or persecution. Some of their stories are harrowing. Many LIPs appear to be involved, voluntarily or not, in multiple proceedings. They don’t do so frivolously or vexatiously: they often feel (rightly or wrongly) they have no choice. And in court they struggle, both to understand and adapt to the procedures as expected, as lay people alongside the lawyers, but also because of their knowledge gap. Tied up in knots (see image), they can’t pretend to be the lawyers they are not, and yet that seems to be expected of them.

Nothing exemplifies this expectation better than the judicial rulings, of which there have been a few, to the effect that LIPs are not entitled to any “special treatment” or separate sets of rules when it comes to procedural requirements or deadlines. See, for example, Barton v Wright Hassall LLP [2018] UKSC 12; [2018] 1 WLR 1119, in which civil procedure supremo Lord Briggs said, at para 42:

“Save to the very limited extent to which the CPR now provides otherwise, there cannot fairly be one attitude to compliance with rules for represented parties and another for litigants in person, still less a general dispensation for the latter from the need to observe them”.

Nevertheless, in my experience as a court observer, judges often do make ample allowance for the lack of representation of some litigants. So do other parties’ lawyers, though this is sometimes not fully appreciated by the LIP, who suspects collaboration with the bench or a “fast one” being pulled when in fact helpful advice is being dispensed for their benefit. But one of the biggest problems LIPs face is just being there on their own. Unless they have a McKenzie friend to help them, they have to manage their papers and take notes and argue their case all at the same time. “What the hell just happened?” is a common reaction after the case concludes. One thing that would certainly help would be access to court recordings or, even better, a speedily produced transcript of the hearing, or at the very least the judgment. Given all the fantastic tools that AI is supposed to be providing for the lawyers, you’d think that one simple thing could be provided for the benefit of litigants.

Kate Leader, Litigants in Person in the Civil Justice System: In Their Own Words (Hart Publishing, £59.50 discounted website price).

Featured image: photo by Isobel Williams @otium_Catulle (who also did the illustration used on the cover).