ICLR in Ottawa (2): Library of Parliament and Supreme Court #CALLACBD2017

We continue our report of ICLR’s trip to Ottawa for the Canadian Association of Law Libraries Conference 2017 with this account of specially organised visits to the Library of Parliament and the Supreme Court of Canada. (Read our earlier post here.) A short stroll from the conference hotel leads us to Parliament Hill, which for a change

We continue our report of ICLR’s trip to Ottawa for the Canadian Association of Law Libraries Conference 2017 with this account of specially organised visits to the Library of Parliament and the Supreme Court of Canada. (Read our earlier post here.)

A short stroll from the conference hotel leads us to Parliament Hill, which for a change is now bathed in sunshine. We are here for a special tour of the historic Library of Parliament, which as I mentioned before is the only surviving part of the original 1860s building, the rest having been destroyed in a fire in 1916. Here is the entire group, assembled on the steps before Parliament:

Here is a side view showing the library behind the main (new) parliament building:

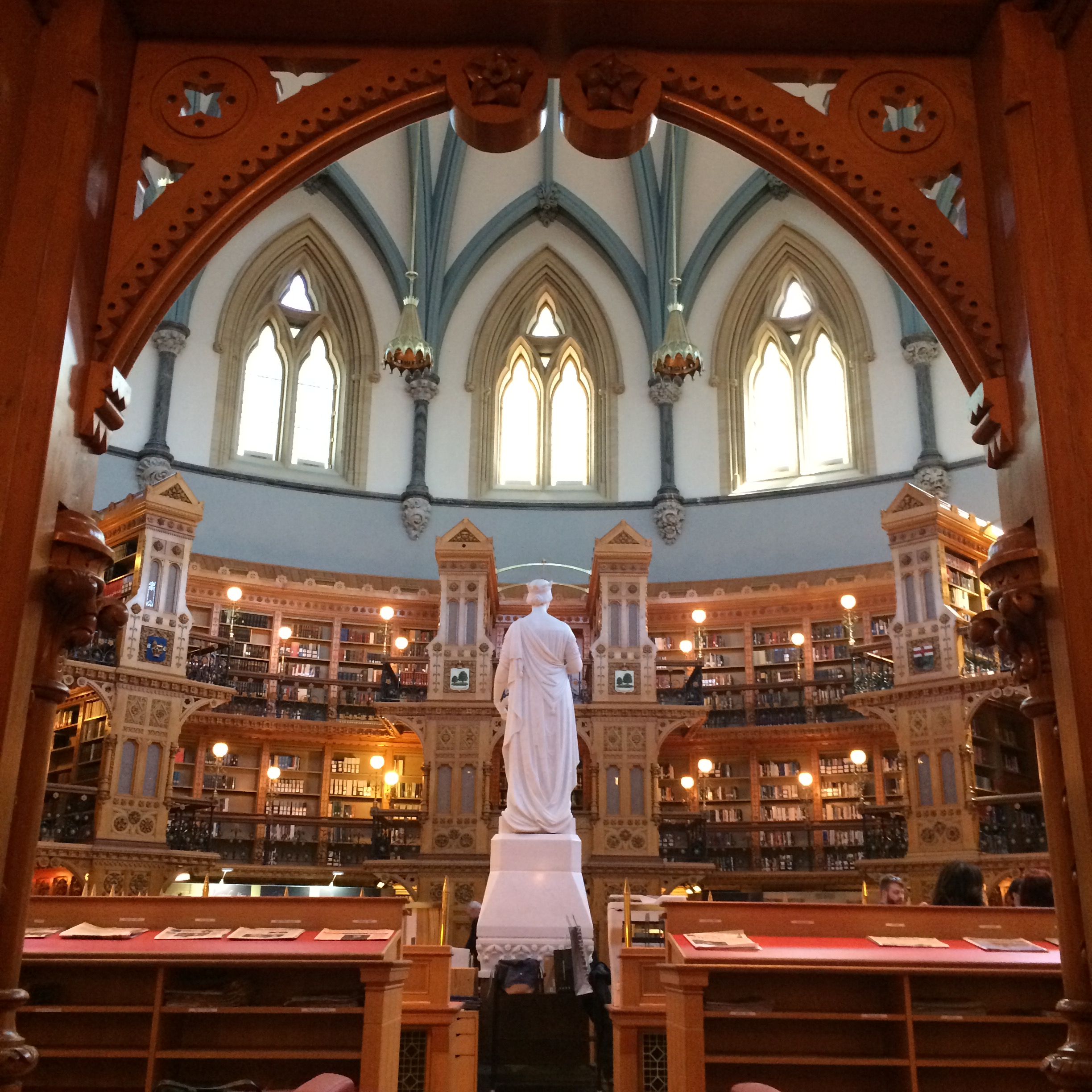

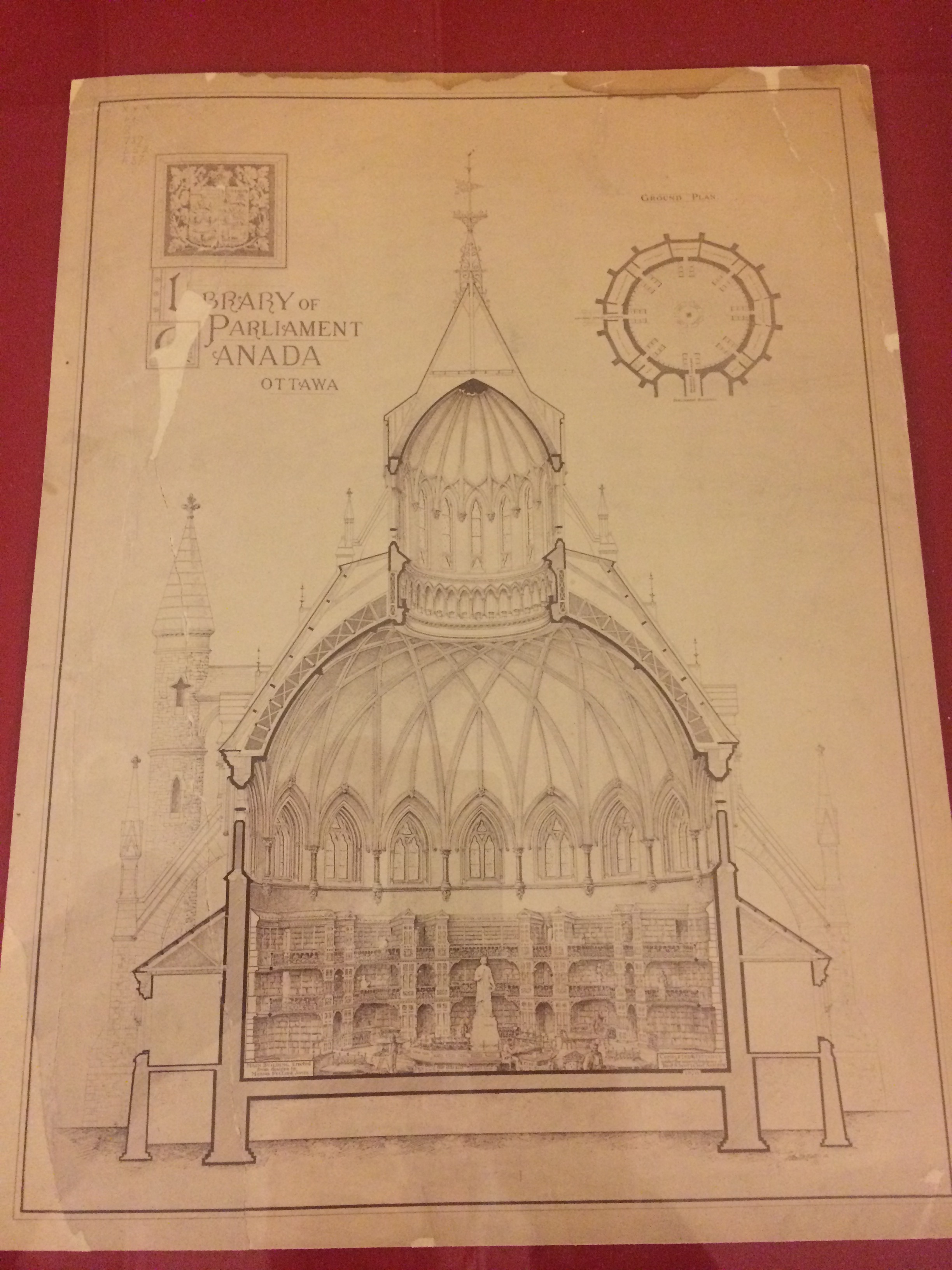

The library is circular, and was apparently inspired by the design of the British Library’s famous reading room at the British Museum. The style is mid-19th gothic revival. In the middle stands a statue of Queen Victoria. I note with interest that there are huge banks of card indexes, though I am told these are no longer used. The library is catalogued and much of its content is now stored on computer.

Library interior; and the plans.

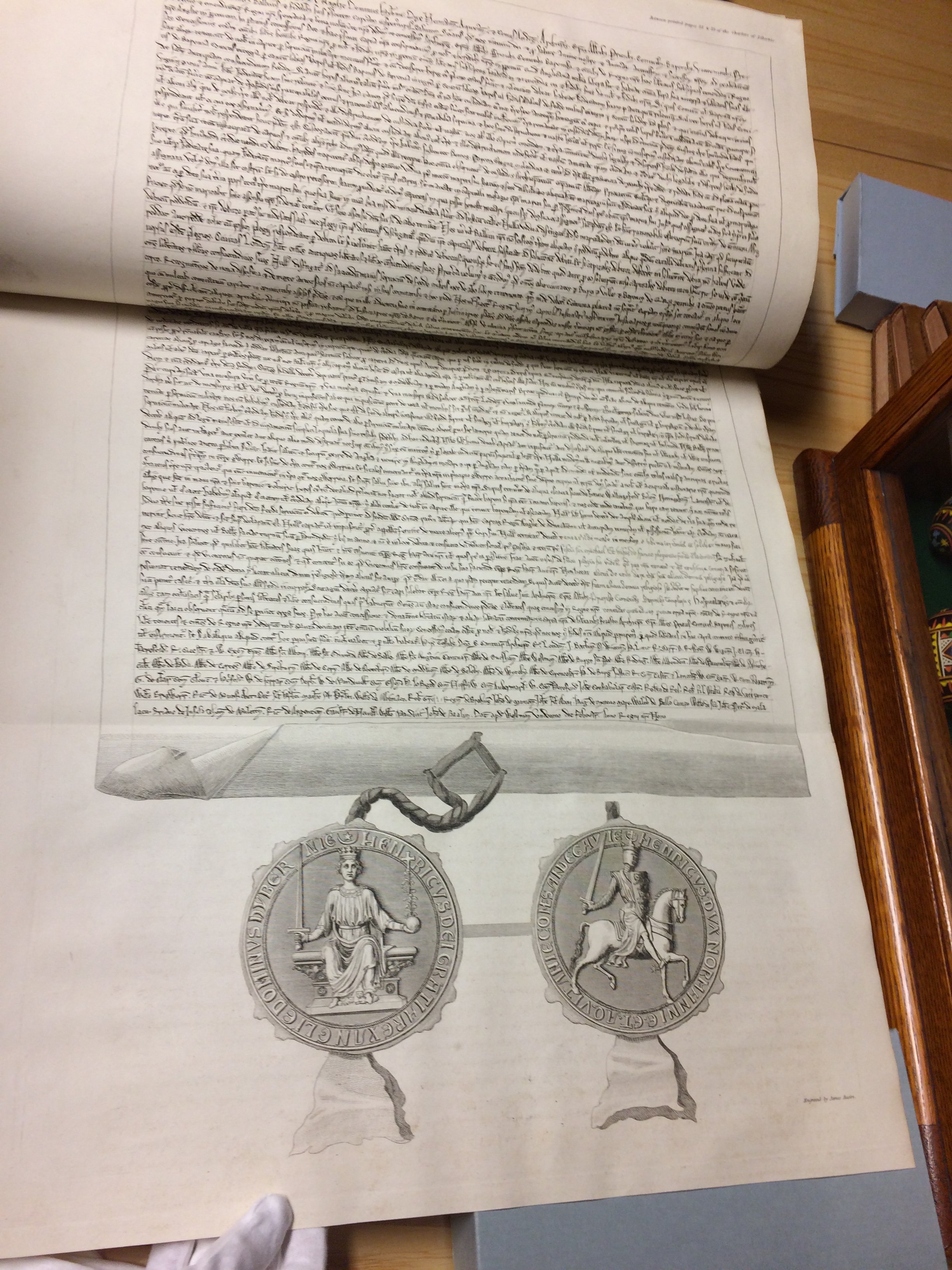

We are given a talk about the library and its work, shown around the gallery and then taken down into the basement stacks for a glimpse at some of the rare books. These include an original printing of Audubon’s Birds of America, and a collection of Prince Albert’s essays and speeches with an affectingly heartfelt handwritten dedication by his widow, Queen Victoria. An early edition of Statutes of the Realm (up to 1377) dating from the reign of George III and complete with engraved copy of Magna Carta, though by no means pocket-sized, was what took my fancy.

The numbers on the tour were strictly limited and had to be booked well in advance. There was a thorough security screening process to be gone through first. It was the same when we got to the Supreme Court of Canada, though for this we were a slightly larger group.

The court building dates from 1939, but the court did not sit here until 1946, the building having been requisitioned during the war years for government use. Before then it sat in another building. The interior of the court shows the bench, which seats nine justices, and counsel’s stand:

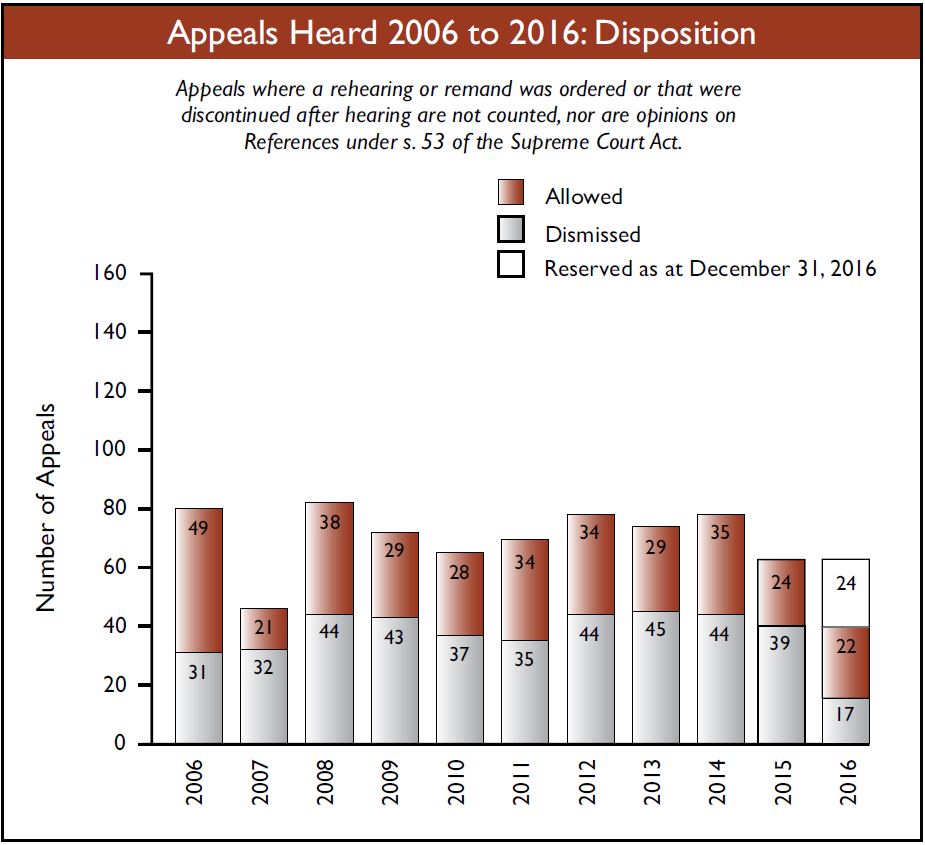

A meeting with the Editor

Afterwards I was privileged to meet, by prior arrangement, with Chantal Demers, Chief Law Editor – Reports Branch, at the Supreme Court. We discussed the process of reporting the decisions of the court (all of which are reported) in both English and French, whatever the language or languages in which the cases were conducted. The parallel French and English text of the SCR is something I am familiar with as a reporter, having frequently cited and referred to cases as a reporter and editor for ICLR and, before that Butterworths. Nearly a quarter (23%) of the cases heard each year in the Supreme Court involve issues arising under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1982, which is coincidentally marking its 35th anniversary in the same year as Canada celebrates her 150th. Another 25% are non-charter criminal law appeals. Most cases require leave to appeal, but a number of appeals are “as of right”, for example where there has been dissent in the Court of Appeal, and leave to appeal is not required. Where leave is required, the case must involve a question of public importance or raise an important issue of law. (This is much the same as for the Supreme Court in the UK.) There are also references from the federal government, requesting an opinion on a point referred by the Governor in Council. Although applications for leave and notices as of right number between 500 and 600 each year, the vast majority of applications for leave are dismissed; and the court actually only hears and disposes of between 50 and 80 cases a year. Of these, slightly more than half are usually dismissed. I know all this because Mme Demers kindly gave me a copy of the annual statistics published for 2006 to 2016, but you can also read it all on the court’s website.

The Chief Justice: Rt Hon Beverley McLachlin PC

The Chief Justice of Canada came to Middle Temple in January 2014 to give a lecture on the subject of: “Is the open court principle sustainable in the 21st century? An examination of the open court principle as a component of the Rule of Law”