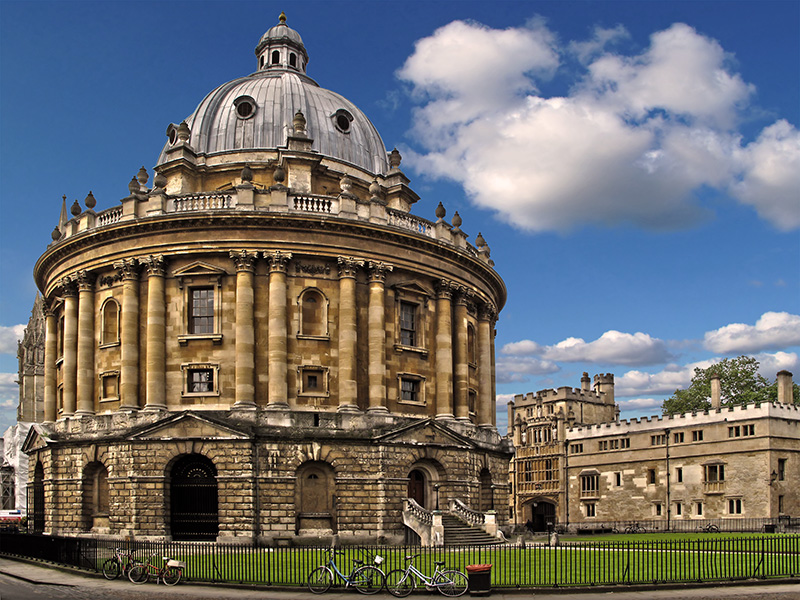

#IALL2016 – Oxford, here we come! (Updated)

Team ICLR is in Oxford for the 35th Annual Course of the International Association of Law Librararies. The theme is “Common Law Perspectives in an International Context”. This is our conference diary, which we’ll top up daily (older entries below). The ICLR team in Oxford is a pair of Pauls – Paul Hastings, Account Manager, and

Team ICLR is in Oxford for the 35th Annual Course of the International Association of Law Librararies. The theme is “Common Law Perspectives in an International Context”. This is our conference diary, which we’ll top up daily (older entries below).

The ICLR team in Oxford is a pair of Pauls – Paul Hastings, Account Manager, and Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content. This diary will be updated regularly, with new content going in at the top.

Wednesday 3 August

In her talk Comparing UK and International Data Protection Law, Dr Judith Townend (pictured speaking) begins by pointing out that until recently media lawyers were far more concerned about the law of libel than that of data protection. But recent developments, including the enactment of the Defamation Act 2013, the growth of privacy claims, and an increasing reliance on it by claimants have made data protection a far more pressing issue. Risks for media organisations include not only civil litigation but also regulatory fines.

The Data Protection Act 1998 was introduced to implement the EU Data Protection Directive 1995, but this is just one of a number of European instruments affecting privacy and data protection, such as arts 7 and 8 of the EU Charter, art 8 of the ECHR and art 108 of the Council of Europe Convention. Following the EU referendum, it remains to be seen what “Brexit” will look like. Having initially suggested that an independent Britain trading with the Single Market would need equivalent standards to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation framework starting in 2018, the Information Commissioner’s Office is now making a rather less specific commitment. (Meanwhile the existing laws continue to apply.)

Dr Townend goes on to discuss two key cases on data protection. First, the somewhat unsatisfactorily named “Right to be forgotten” – effectively a right to erasure, on which the European Court of Justice gave its now famous ruling in Google Spain v AEPD and Gonzalez (Case C-131/12). The requirement to remove links on search engine results to content that is inaccurate, inadequate, irrelevant or excessive has been criticised as a form of censorship or rewriting of history, but of course the original content remains even if the links to it are removed. Google instituted a procedure for complainants to ask for links to be removed but there are concerns over how transparent that process is, how fair, and how easy to circumvent (the “whack-a-mole” scenario, in which new versions of a story keep popping up).

By confining its effect to Europe, it raises the possibility – demonstrated in the recent PJS (anonymous celebrity threesome) case – of “geo-blocking”, ie preventing access to certain content from within specified geographical areas (in PJS it was England and Wales – but not Scotland, though it appeared from a question after the talk that Google had blocked Scotland as well, an example of excessive enforcement of the court’s injunction, whether through ignorance or inflexibility is not clear).

A recent Belgian case (Olivier G v Le Soir) has gone further than Google Spain, in that it has required actual erasure of details (anonymisation) in an historic newspaper article. English courts have not dealt with this issue, though in general the principle of open justice requires media reports of judicial proceedings to be allowed to name the parties.

In the second major case on data protection, the ECJ upheld the challenge of Max Schrems against the Irish data protection commissioner’s failure to consider the adequacy of the “Safe Harbor” agreement in protecting data passed from Facebook in Ireland to the USA (see Schrems v Data Protection Commissioner (Case C-362/14) [2015] WLR (D) 403). The court’s decision that Safe Harbor was inadequate has led to the new Privacy Shield agreement, adopted on 12 July 2016.

Dr Townend concludes that:

- There are bound to be more cases concerning source material and RTBF rights, raising interesting conundrums for media orgs, online archivists/librarians etc.

- Expansion of media litigation to data protection is very significant – provides a more flexible option for claimants than defamation

- Legal records, particularly those relating to criminal data, could prove particularly difficult to navigate in the developing data protection context

This talk, combined with the yesterday’s on Big Data (see below), convinces me that the legal implications of data protection and the regulation of data commerce are at the thin end of a very long, very big wedge of future development. Our data is our digital blood. The vampires are out there, coaxing us with honeyed seduction; but so are the angels of the blood transfusion service. The law needs to catch up… and I probably need to work on some better metaphors.

Later, on my colleague’s recommendation, I visited the chapel of Keble College, which I would guess to date from the late 19th century (Victorian Gothic). The narrative mosaics on the walls have a softness of texture that makes them appear almost like stitchwork (very gros point), illuminated in the stained glass light of the windows. Only after absorbing these competing wonders (it is all rather vibrantly colourful) do I notice the brilliantly painted tubes of the organ pipes, like a giant child’s multi-hued crayons. Here they are:

Tuesday 2 August

Speaking on the topic of Big Data, Algorithmic Regulation and its Implications, Professor Karen Yeung, of the Dickson Poon School of Law at King’s College London, confesses that it was Ruth Bird, now the Bodleian Law Librarian at Oxford (and primary organiser of the present conference), who gave her her first glimpse of the Internet. That was more than 20 years ago, at the law firm in Australia where she then worked.

The internet has turned out to be extraordinarily powerful, heralding a second industrial revolution, which will be powered by the engine of big data. Mining for value in big data has been described as “bio-prospecting”. The critical feature of big data analysis is that the useful patterns and correlations are not capable of analysis by human or ordinary computing techniques, because the volumes of data are simply too vast. It relies instead on machine learning routines to convert recognisable patterns into useful knowledge.

There are differing views as to whether the harnessing of big data analysis is a good thing or not. Prof Yeung’s view is not optimistic. In discussing her concerns, she introduces us to some interesting new terms. “Algorithmic regulation” is one of them. Another (or possibly a synonym) is “Algocracy” – a new form of social ordering, based on the logic of mathematics and statistics. (Already I feel as though we have entered the world of a dystopian sci fi novel by Philip K Dick…) By the time Prof Yeung has finished I have also been introduced to the word “Algorigation” – apparently a shipping or mashup of algorithm and aggregation. (So presumably you can “algorigate” useful or at any rate useable data, using algorithms.) To combat the possible harm from algorithmic systems, there are now increasing calls for mechanisms to secure “algorithmic accountability”.

If this isn’t scary enough, Prof Yeung proceeds to show some slides based on a vision of the future in which, essentially, Google is God. The future is nearer than you think, for this was the year 2018 as viewed from the quaintly historic perspective of five years ago, by the World Economic Forum in its 2011 report Personal Data: The Emergence of a New Asset Class (PDF) – see from p 20 onwards.

The vision depicts Dianne (see image above), who has two teenage daughters and an elderly father. She wears sports shoes that send exercise data to her health insurer, earning her credits against the cost of cover, discounts on food and medicine etc. Her daughters get credits too, so all the family compete to exercise the most. The girls’ use of the internet is safely monitored and Dianne gets a report that shows they’ve not looked at anything inappropriate. But their activity data earns them coupons and credits against fun stuff in the holidays. Cool!

With her dad, Dianne no longer needs to worry if he’s taken his meds for early-onset Alzheimer’s, as the health insurer is monitoring it all with compliance tracking tool that feeds into medical research. (Earlier, Prof Yeung showed us a picture of the mini-bar “smart tray” in her hotel room that automatically bills you when a snack or drink is removed – presumably the same could be used to dispense pills and monitor med-compliance.) And when she goes to visit her dad, she doesn’t need to ask him how he is or whether he’s remembered to take his meds – she already knows, so instead she can devote her visit to “quality time”.

Prof Yeung is not quite so sanguine as this upbeat report about the benefits of the brave new world, described as an “arid wasteland” ruled over by a “Big Other”. It’s all very well if all the data about you are correct and the decisions based on beneficial, but the consequences of an adverse decision or profiling can be profound and almost impossible to reverse. There is a risk of “discrimination by design”. And it is clear from the ease with which people sign away rights by accepting terms and conditions when purchasing apps and the like, that informed consent is rarely genuinely obtained, or indeed genuinely “informed”. The lack of transparency in the way mass collections of data like NHS patient records are provided to organisations like Google without individual consent is also frightening.

So more, much more, needs to be done. She concludes that

The law (and legal scholars) have a vital role in responding to the challenges of securing algorithmic accountability, which is likely to require innovation in conventional understandings of the mechanisms through which legal, constitutional, democratic and moral values are protected.”

[Incidentally, if you think the world of Big Other or indeed Big Brother isn’t already here, read this from the Irish Times last week: Berlin Letter: Draconian public order looms via smartphone.]

I said earlier that Professor Yeung was based at the Dickson Poon School of Law but in her honour I’m beginning to wonder if we shouldn’t be calling it the Philip K Dickson Poon School of Law. (Objection! All right, strike that from the record.)

Here’s a picture of that lovely Oxford “bridge of sighs” (Hertford Bridge) that I took on the way home from the pub tonight.

Monday 1 August

One of today’s sessions is about Law Reporting in England 1550-1650. Emeritus Professor Sir John Baker told us about what might be called the dawn of proper law reporting, when the Year Books (which largely covered the procedure, but not the decision, in cases) gave way to the Nominate Reports, in which the determination of a point of law was recorded as a precedent. [I hope I have captured the gist of what Prof Baker said, in this inevitably inadequate interim note: full proceedings of these sessions will be published by the IALL in the International Journal of Legal Information.]

The first of these nominate reporters, Edmund Plowden, was conscious of the new departure he represented, and apologized in his preface in 1571 for putting his own name to the volume. His reports contained most of the essentials of a modern law report, though he presented the pleadings and argument in law French – there was some doubt at the time as to whether English law could really be expressed in the English language! Following the judgment, he added his own comments in a different typeface, clearly separating them from the record of the decision – something later reporters and editors were less scrupulous about (in some cases marring the accuracy of their record in their attempts to improve the expression of the court’s decision). That was one of the complaints leveled against Sir Edward Coke, whose eventual dismissal from office in 1616 marks the other great 400th anniversary this year.

Coke’s eight notebooks contained cases he had been involved in or had heard about. What he viewed as “perfecting” for publication might involve considerable rewriting. His annotations and commentary were woven into the report itself, making it hard to separate out the ratio decidendi (the decided point of law). In 1616 a dossier was sent to the king setting out the many criticisms of Coke’s conduct as a judge and as a reporter, in consequence of which he was dismissed from office. (The real complaint, however, was his tiresome insistence on standing up for the rule of law. )

Plowden and Coke published reports in their own lifetime, but other reporters, such as Sir James Dyer, were published posthumously. So although the cases he covered in the 1530s pre-dated Plowden, it was not until 1586 that an edition prepared by his nephews, two law students, appeared in response to pressure to make their useful contents more widely available. Dyer’s reports, including over a thousand cases, were barely edited. But many of the entries in his notebooks were left out of the original edition, including (surprisingly) those on the subject of habeas corpus. Another 400 entries would be added in an edition by Baker for the Selden Society.

It seems the practice of barristers and judges keeping manuscript notebooks of useful cases may have been widespread, but few of them ended up being published and of those that did, none bear comparison with Plowden or Dyer. Great judges were not always good reporters.

In 1617 an absurdly ambitious scheme of official law reporters was introduced by the Lord Chancellor, Sir Francis Bacon, with conspicuous lack of success. Only two reporters were appointed, and only 23 cases were published, none of which was from Bacon’s own court. No new law reports appeared until 1641. In the meantime, such reports as there were of what passed in court were to be found in manuscript only – and still await their sympathetic modern editor.

Prof Baker’s talk was followed by one from Professor David Ibbetson on Precedent and Authority: the Continental Dimension. This discussed and partly dismantled the traditional view of the distinction between common law and continental civil law systems, in which precedent is only viewed as playing a significant role in the development of the law in common law systems.

Prof Ibbetson traced the development of the concept of binding precedent as something that depended upon the appearance of reliable and comprehensive law reporting, so that it was not really until the beginning of the 19th century that both were in place. But the practice of following previous cases was not a new one. What changed was the idea of authority.

In medieval systems, according to the dialectic theory of argument, authority could be either “necessary” (based on something then considered unquestionably true, such as the Bible) or “probable” (an assertion or statement which could be relied upon at least as a starting point, unless the contrary were shown: for example, it was assumed a learned man could be trusted “in his own art”). Early works of legal dialectic would argue from authority in this fashion.

Judicial precedents were regarded as probable authority, so a later court could depart from them if convinced by alternative argument. England had a notion of precedent from the early 17th century, when the printing of reports enabled the courts to rely on earlier cases.

On the continent, the argument from authority took the Roman jurists as necessary authorities, while treating medieval lawyers writing in the Roman tradition as merely probable authorities. The continental approach developed as one in which it was the law that was to be followed, not the cases that were merely illustrations of the law, though these could still be consulted on that basis. Continental case reports differed from English law reports in that while they recorded the decision reached by the court, the reasons for that decision were constructed and explained by the reporter or editor of the volume, and so were more like a commentary or text book. They were concerned with deriving principles from the cases, not recording the arguments made in them.

In the 16th century there was a vast amount of legal literature on the continent, in which you could find authority for almost anything and its opposite. The more flexible English model enabled judges to build on and develop the law without the rigidity which bound the continental approach.

[As with Professor Baker’s talk, I hope my necessarily sketchy notes are not inaccurate in substance. Do please let me know if I have got anything wrong.]

In the evening, there was to have been a barbecue on the lawn outside, but the English weather being what it likes to be, the event was held in glorious hall of Keble College instead. There were still burgers and grilled chicken, salad and strawberries and cream to follow (or profiteroles), but the atmosphere was more that of a Hogwarts end of term shindig, sponsored by Hein Online, whose boss Shannon Hein accepted the thanks and tribute of the company attired in a Harry Potter scarf (House of Gryffindor). Here he is:

Sunday 31 July

The conference is being held at Keble College, but the opening reception is at the offices of the Oxford University Press. We are welcomed by IALL President, Jeroen Vervliet, who flags up an important change in the scheduled talks. To mark the uncertainty of the times we live in, the talk on Indian insolvency law due to take place tomorrow will now be replaced with one on the Legal Consequences of Brexit!

On that topic, the Registrar of the University of Oxford, Professor Ewan McKendrick, speaking next, says that while democracy must be recognised, Oxford voted overwhelmingly to stay, and the university would be lobbying to ensure that Britain can “stay to the full extent possible consistently with being out”. Scholarship, he says, neither needs nor recognises national borders. Even a subject like law, which does have national or jurisdictional boundaries, remains international as a subject.

Then Andy Redman, editorial director of law, OUP, gives us a Brief History of Law Publishing at Oxford University Press. Their mission, as a university and as a publisher, is excellence in research, in scholarship, and in education. They are proud to host the opening of the 2016 conference.

As a publisher, Oxford likes to keep the author front and central: even online, the voice and identity of the expert should not be subsumed into the mass of legal information. (This emphasis on provenance and authority certainly chimes with us, since, as with the most authoritative textbooks and commentaries, we the need to preserve the provenance and identity of our law reports.)

After all that talking, what we need now is some music. Step forward, suitably attired in 17th century garb, the Oxford Waits, with lute, fiddle, hurdy-gurdy and a sort of turbo-recorder thing, called a shawm. After a brief explanation, they regale the company with assorted ballads and stomps of the 17th century. Afterwards, Paul M (as an amateur classical guitarist) takes the opportunity of a lute masterclass from lutenist Edward Fitzgibbon.

Team ICLR at IALL2016 are Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content, and Paul Hastings, Account Manager – the two Pauls. Our stand is on the left back as you walk into the exhibition hall for coffee, tea or lunch. This is what it looks like:

This post was written by Paul Magrath, who also tweets as @maggotlaw. It does not necessarily represent the opinions of ICLR as an organisation.

Comments welcome on Twitter @TheICLR.