Annual Notes 2014: ICLR’s review of the year’s legal news (part 1)

Court procedure may be getting less adversarial but the relationship between lawyers and the executive has become more so, as the number of defeats suffered by the government in judicial review proceedings grows steadily greater. No wonder the government wants to cut back on the scope for bringing judicial review, yet even in this endeavour… Continue reading about Annual Notes 2014: ICLR’s review of the year’s legal news (part 1)

Court procedure may be getting less adversarial but the relationship between lawyers and the executive has become more so, as the number of defeats suffered by the government in judicial review proceedings grows steadily greater. No wonder the government wants to cut back on the scope for bringing judicial review, yet even in this endeavour it has suffered several setbacks.

Other trends discernible in the legal world of 2014 included

- a push for open justice and transparency, particularly in the family courts, which saw a major reorganisation during the year, all under the energetic presidency of Sir James Munby;

- regulatory woes, with further setbacks in the controversial QASA scheme for criminal advocacy and a rocky ride for ABS firms, among other acronyms.

- Legal aid protests and walk-outs, and yet more judicial review, with the criminal Bar and solicitors refusing to accept fee cuts and contract reductions.

- Frustration and uncertainty over the setting up of a comprehensive inquiry into historic child abuse, and the choosing of a suitable chairperson.

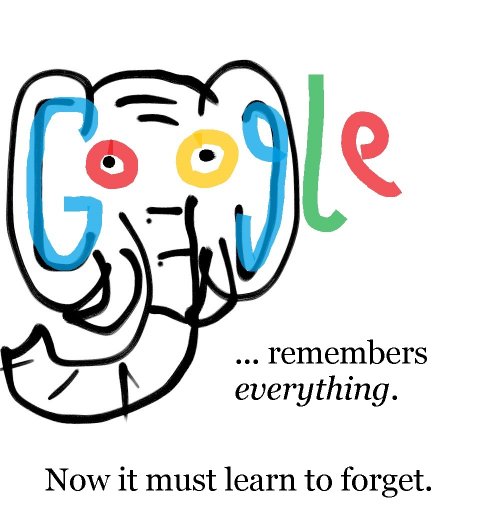

- In Europe, the Court of Justice opened a can of worms with its championing of the so-called Right to be Forgotten (ie the removal of out of date, irrelevant or excessive data about individuals in search engine indexes) in its judgment in Google Spain LS v AEPD (Case Cp-131/12).

- In South Africa, the televising of the Oscar Pistorius trial caused a worldwide sensation, putting a spotlight on the country’s criminal legal system and making armchair advocates of everyone.

- Almost as fiercely followed was the “phonehacking” trial in which various employees and former employees of the News of the World faced charges of conspiracy to intercept communications and other crimes.

Meanwhile, even closer to home, the year also saw a major upgrade to ICLR Online, with its cleaner, simpler, faster “Unified Search” for caselaw, its new Dashboard feature, and an overhaul of its user interface optimized for the growing number of smartphone and tablet users. (Stand by for further major improvements in 2015.)

In two linked posts we survey the key developments in legal news and events from 2014. This is part 1. Part 2 will follow shortly.

January: Transparency and Open Justice

On 8 January the Chief Justice of Canada, the Rt Hon Beverley McLachlin PC, gave a ringing endorsement to the ideas of open justice and public access to the legal system in a speech to a packed Middle Temple Hall hosted by the Bar Council as part of its International Rule of Law series.

The transparency theme kicked off in a big way on the ICLR Blog with our discussion of a case that had gestated the previous summer and autumn, and continued to generate judgments and commentary well into 2014, about an Italian woman whose baby had been removed, first by caesarean section and later (for adoption) by social services, at the behest of the courts: The Curious Case of The Court, The Commentators, The Woman, and Her Baby.

The storm of controversy whipped up by Christopher Booker’s initial reporting in the Saturday Telegraph duly abated when, prompted by the President of the Family Division, Sir James Munby, the courts and the various authorities started putting more accurate information into the public domain. It was a good demonstration of how sunlight really is the best disinfectant, and also of how well-informed bloggers were able to correct the misapprehensions and exaggerations of the axe-grinding end of the news media.

Later the same month, the President (left) issued Practice Guidance (Family Courts: Transparency) [2014] 1 WLR 230 and Practice Guidance (Court of Protection: Transparency) [2014] 1 WLR 235 which require courts in the Family Division and the Court of Protection respectively to give judgment in open court by default, and only suppress names or documents, or entire judgments, if the circumstances genuinely warrant it. In the guidance he states:

Later the same month, the President (left) issued Practice Guidance (Family Courts: Transparency) [2014] 1 WLR 230 and Practice Guidance (Court of Protection: Transparency) [2014] 1 WLR 235 which require courts in the Family Division and the Court of Protection respectively to give judgment in open court by default, and only suppress names or documents, or entire judgments, if the circumstances genuinely warrant it. In the guidance he states:

“In both courts there is a need for greater transparency in order to improve public understanding of the court process and confidence in the court system.”

Later in the year, in August, Sir James embarked on a consultation process to ascertain the views of all interested parties in proposals for further transparency.

Also in August, a group of legal bloggers led by Lucy Reed (aka Pink Tape) set up The Transparency Project, with a new website and blog, specifically aimed at dispelling misunderstanding and misreporting of family cases. It is now also becoming an independent voice as one of the bodies responding collectively to the President’s consultation process.

Not all of those responding to the President’s consultation were entirely positive about increasing transparency, particularly in relation to proceedings involving children, and the year ended with a report by Frances Gibb, legal editor of The Times, suggesting he might have to rein in his plans after hitting a “wall of opposition”. She reports that:

Resolution, the association of 6,000 family lawyers in England and Wales, has questioned whether there is “genuine demand” for more openness. It said: “We believe that any benefit to the public would be far outweighed by the disadvantage to children and the court user in relation to their privacy and ability to give their best evidence.”

Well, there is certainly genuine demand, but whether it is justified or ought to override other considerations is a different matter, and one which the President must now consider. (See further, Transparency Project, Is there a “wall of opposition” to greater transparency in family courts?)

Also coming out strongly in favour of open justice, later in the year, was Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury, giving a speech to the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents’ Club in August on Judges, Journalists and Open Justice.

February: ICLR Online v 2

The biggest event in the year’s shortest month was the launch of ICLR Online version 2 (above), which involved a complete redesign of our dedicated case law platform. Features include:

- A new user interface optimized for tablet and smartphone touchscreens, as well as desktop and laptop computers

- A new Dashboard page, offering a clean, clear view of updated and readily available content

- Single search form combining case search and Citator+ (index) searches

- Advanced search tools providing faster, more comprehensive searches across both ICLR and external content

- Consolidated results making navigation to reports, index cards and BAILII transcripts quick and logical.

For a free trial (if you have not already tried it) click here.

March: Grayling Day

According to impeccable sources (a stub on Wikipedia) a Grayling is a kind of fish (probably a slippery customer), and a “Grayling day” is an angler’s holiday in the autumn, when fishing gives way to drinking (like a fish). But the nationwide protests that took place on 7 April took the name Grayling Day from Chris Grayling, the current Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice, in recognition of his role in driving forward and implementing the cuts to legal aid about which the protesters were complaining. Far from being a celebration it was characterised by one speaker as Grayling’s “day of shame”.

The protest march and walkout was organized by the Justice Alliance and supported by the Criminal Bar Association (CBA), the London Criminal Courts Solicitors Association and Criminal Law Solicitors Association. You can read about it on Legal Voice, and also in Counsel magazine online.

On this blog, we covered it somewhat tangentially, by virtue of the appearance on the march of the actress, Maxine Peake (right), who plays Martha Costello QC in the TV courtroom drama Silk. That series came to an end this month and was widely missed, as much by those who enjoyed complaining about its inaccuracies, as by those who enjoyed watching its somewhat extravagant view of the criminal law. (An extravagance Chris Grayling would surely say we can no longer afford.)

On this blog, we covered it somewhat tangentially, by virtue of the appearance on the march of the actress, Maxine Peake (right), who plays Martha Costello QC in the TV courtroom drama Silk. That series came to an end this month and was widely missed, as much by those who enjoyed complaining about its inaccuracies, as by those who enjoyed watching its somewhat extravagant view of the criminal law. (An extravagance Chris Grayling would surely say we can no longer afford.)

Grayling was the target of complaints about other policies during the year, especially his privatisation of the probation service and his so-called Prisoner Book Ban, a campaign against which also emerged this month. The ban was actually just on receiving books in parcels, but it still seemed contradictory to the stated rationale for imposing it, which was to improve prisoner rehabilitation, a point made eloquently by the judge (Collins J) who, on one of Mr Grayling’s several judicial review setbacks, ruled the policy unlawful: see Regina (Gordon-Jones) v Secretary of State for Justice [2014] EWHC 3997 (Admin) at [46]:

In the light of the statement made about the importance of books and the absence of any intention to prevent or interfere unreasonably with prisoners being able to have access to books, to refer to them as a privilege is strange.

April: Fools…

Writing a good April Fools spoof is difficult these days, when so many genuine proposals for transforming civil or criminal justice have the air of calculated idiocy about them, but ours this year had the benefit of being inspired by a judge, over a couple of pints in the pub behind the law courts (the so-called Seven Stars Symposium). The images below (“artist’s impressions) give some idea of what’s proposed. The blog was entitled: Privatised civil justice – how it might look.

… and Fears

… and Fears

The risk to the “living instrument” of the common law from more genuine recent developments, including the erosion of adversarial process and the lack of open justice, particularly in relation to their effect on the role and value of law reports, was the subject of a more serious discussion in The end of the road for the Common Law?

May: Operation Cotton

One aspect of the latest round of cuts in criminal legal aid was to reduce, drastically (ie by 30%), the fees payable to those counsel accredited to work on Very High Cost Cases, usually complex fraud trials. In one such trial, R v Crawley and others, the five defendants were all deprived of counsel, who had resigned over the paucity of their payment, or rather refused to sign up to a revised version of their contracts under which they would have been paid less than originally stipulated.Instead, the defendants were temporarily represented pro bono (ie without payment) by the Prime Minister’s brother, Alex Cameron QC, on an application to stay the prosecution on the ground that to proceed would amount to a violation of their right to a fair trial. (Weekly Notes, 9 May 2014).

In a judgment given on 1 May, the trial judge, HHJ Leonard, granted the application. This sent shockwaves through the corridors of Petty France, where the Ministry of Justice is housed, and in due course they appealed. The Court of Appeal [2014] EWCA Crim 1028 reversed the judge’s decision, apparently on the basis that the MoJ had a joker up its sleeve all along: to compensate for the lack of VHCC accredited counsel, it would beef up (essentially resuscitate) a dormant Public Defender Service, which soon afterwards signed up a few senior barristers to give it a show of credibility (apparently at rather higher cost to the treasury than maintaining the original VHCC scheme): see PDS, PDQ! Operation Cotton and Operation (saving the MOJ’s) Bacon.

(Also, for the sequel: Weekly Notes, 30 May 2014.)

It was only after a protracted and somewhat contentious negotiation between the Criminal Bar Association and the MoJ that a new deal was forged in which concessions were made on both sides, leaving neither truly satisfied, but ensuring that VHCC barristers would now be available. (The PDS scheme seems to have relapsed into dormancy again.)

But there was another major development in May. Remember this?

Yes, this was also the month when the Court of Justice of the European Union gave its now unforgettable (though densely worded) judgment in Google Spain SL v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) (Case C-131/12); [2014] WLR (D) 202; (£) [2014] QB 1022.

Yes, this was also the month when the Court of Justice of the European Union gave its now unforgettable (though densely worded) judgment in Google Spain SL v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) (Case C-131/12); [2014] WLR (D) 202; (£) [2014] QB 1022.

It sparked a row between those who supported the court’s defence of privacy and those who thought it should be overridden by the right of the public to know. There were accusations from the latter camp that the erasure of links would amount to censorship, that it was a charter for criminals, paedophiles and politicians to clean up their pasts, and so forth. Google set up an advisory council to determine how to comply with the ruling, and embarked on a roadshow to discuss the matter with the public.

In all the fuss, what was overlooked by most was that the number of links suppressed by reason of the Right to be Forgotten was massively dwarfed by the numbers routinely taken down for, eg, copyright infringement, or government secrecy, etc. – as became clear when google published its own Transparency Report.

(See, variously, Weekly Notes, 16 May 2014; Weekly Notes, 17 October 2014; and Weekly Notes, 3 October 2014.)

June: Phonehacking…

The trial of the century, as it was called by some, drew to a close with the jury finding Andy Coulson, former editor of the News of the World, guilty of conspiracy to intercept communications, but returned a verdict of not guilty against his co-defendant, and former lover, Rebekah Brooks, and Stuart Kuttner, former managing editor of NoW.

The prime minister David Cameron put his foot in it by commenting on the verdicts just given, when the jury were still deliberating on other counts. (Weekly Notes, 26 June 2014.)

Sentencing was postponed till 4 July (Weekly Notes, 4 July 2014).

… and BIALL

June was also when the British and Irish Association of Law Librarians held their annual conference, in Harrogate this year. One of the key speakers at the plenary sessions was ICLR’s own Daniel Hoadley, who gave a popular and much quoted talk on The Curious Case of the Judgment Enhancers. Reproduced in full on this blog, it has proved one of the year’s most popular and oft linked-to posts. As he explains:

Law reporting is almost as ancient as the common law itself and has been absolutely central to its development. Without law reporters and their reports, English common law would never have developed.

He goes on to cover the history and purpose of law reports and explain their current importance in a wired-up world which is often tempted to prefer the immediacy of raw content over more refined and reliable (and citable) versions.

For our review of the remainder of 2014, see Part 2, coming soon.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content at ICLR. It does not necessarily represent any views of ICLR as an organisation.