A celebration of law reporting in Melbourne

On a recent trip to Australia, ICLR co-hosted an evening with the Council of Law Reporting in Victoria, celebrating the contribution of law reporters to the rule of law. This post sets out the speeches given on that occasion.… Continue reading

The event took the form of a convivial gathering at the Essoign Club in Melbourne on the evening of 29 August 2022. The guests included judges, lawyers, academics and librarians. Following an introduction by Laurie Atkinson, Director of the Law Library of Victoria and Supreme Court Librarian, the main speech was given by Justice Catherine Button, Judge of the Trial Division of the Supreme Court of Victoria, and Chair of the Council of Law Reporting in Victoria.

A Salute to the Law Reporter

by Justice Catherine Button[1]

Acknowledgement and welcome

1. Good evening.

2. I would like to acknowledge the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation as the traditional custodians of the land on which we gather. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. I extend that respect to any Aboriginal people or Torres Strait Islanders here today.

3. I would like to welcome, and thank, everyone for attending this gathering to acknowledge the contribution of law reporters to the rule of law.

4. As Chair of the Council of Law Reporting in Victoria, I particularly want to extend a warm welcome to visiting colleagues from the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting England and Wales (ICLR). We are delighted that you can join us.

5. I would also like to acknowledge the presence here this evening of judicial colleagues from the Federal Court, and the Appeal and Trial Divisions of the Supreme Court, including the former President, Chris Maxwell, and my predecessor as Chair of the Council of Law Reporting in Victoria, Justice Macaulay, who served in the role with great care and vision. I also acknowledge the attendance of the current, and two former, Solicitors-General.

6. The Chief Justice, Anne Ferguson, sends her apologies — she has been called away overseas on a well-earned period of leave.

7. It is gratifying too that so many law reporters have accepted the invitation to attend this evening.

The rule of law and law reports

8. The rule of law depends on a robust common law system, one which has at its core the incremental judicial development of legal principles to meet changing societal needs.[2]

9. Law reports are indispensable to the effective operation of the common law system, and our law reporters are its ‘unsung heroes’.[3]

10. Law report series of high quality enable practitioners to identify and cite cases that establish or usefully elucidate the principles. Without law reports, practitioners would be left to wade among the ever-growing mountain of unreported cases, and courts would be burdened — to a greater extent than is already the case — by the citation of earlier decisions based on patterns of factual similarity, rather than the application of cases of high authority to the facts of the case at hand.

History

11. I have just referred to law reports of ‘high quality’. That was not a mere passing observation, as those of you familiar with the history of the development of law reporting will know.

12. The history of law reporting is almost as old as the common law itself. Some date the practice of law reporting back to the transcriptions from the Plea Rolls in 1189. Modern law reporting is, fortunately, easier to navigate than the handwritten legal manuscripts produced by medieval monks and scribes dating from the 13th to 16th centuries, with red lines linking one case to another.[4]

13. By the around 16th century, the Year Books were followed by the nominate reports, where individual reporters were publishing volumes or series of case reports under their own names.[5] These nominate reports were at times mediocre, and their poor quality was seen to risk leaving broader English society with the mistaken impression that the quality of its judges was equally poor.[6]

14. Sir John Holt, former Lord Chief Justice of England, famously warned in the case of Slater v May, reported in 1704, that the nominate reports, which his Lordship referred to as ‘these scrambling reports’, threatened to make judges appear to posterity as ‘a parcel of blockheads’.[7] Ironically for the Lord Chief Justice, his words are only available to us via, you may have guessed, the nominate reports published by Lord Raymond.

15. In the late 18th century, ‘authorised’ reports began to emerge, as judges often granted select law reporters access to judges’ notes of the cases being reported, with the judges sometimes reviewing and correcting the reports.[8]

16. The rise of early authorised reports, however, did not transform the mass of available law reports into the intelligible corpus of judicial decisions we have come to expect today. Rather, Lord Westbury famously described the mass proliferation of nominate and authorised law reports in the 18th and 19th centuries as ‘a great chaos of judicial legislation’.[9]

Modern law reporting

17. It was not until the founding of the ICLR in 1865 that the situation greatly improved and modern law reporting came of age.

18. Nathan Lindley QC, who was to became Master of the Rolls, was instrumental in founding the ICLR and argued that the only decisions which should be reported are those:

(a) which introduce a new principle or rule of law;

(b) give an authoritative interpretation of a new statute;

(c) concern important matters of practice or procedure; and

(d) to use Lindley’s words, are ‘for any reason … peculiarly instructive’.[10]

19. The ICLR’s influence continues to guide law reporting in Australia. The State of Victoria adopted a system of authorised law reporting in 1875, overseen by the Council of Law Reporting in Victoria.

20. The Victorian Council’s criteria were also influenced by Lindley’s, namely that cases either deal with an aspect of the common law which is novel, involve a departure from a long line of authority, or involve a survey of authorities or a comprehensive restatement of principle.[11]

21. This selectivity is an essential feature of effective and relevant law reporting, particularly where widely accessible, online databases contain, what Professor Emeritus Michael Bryan has called, ‘both gold and dross’.[12]

22. As a generator of much such ‘dross’, I will forgive my former Equity lecturer for the perhaps tactless description of many trial judgments. But it is important not to confuse the value to litigants of a judgment which provides a clear statement of why a case has been decided as it has, on the facts, and a judgment which is of wider utility and importance to the proper and efficient functioning of the common law system.

23. The task of identifying the gold among the dross falls primarily to the editors of law reports, who select cases for reporting. That is no small undertaking.

24. But the task of making the law report useful — and accurate — falls to law reporters.

25. As many of you would know, writing a good headnote is difficult. I well remember delivering my first CLR report to the late (and great) JD Merralls only to have it dissected and eviscerated as I sat across the desk while Merralls went over it with his very active pen.

26. In A Manual on Law Reporting, Naida Haxton, a former editor of the NSW Law Reports, sets down the following three principles for a good headnote and catchwords:

(a) a reporter must have a thorough understanding of the point on which success or failure in the case turned;

(b) a reporter must analyse the case into the legal principles involved and work out the classifications where a lawyer would expect to find a case on the point; and

(c) a reporter must be able to express the essence of the decision accurately, briefly and comprehensively.[13]

27. Haxton also placed great emphasis on brevity, so far as it was consistent with clarity.[14]

28. The virtue of brevity, however, can have its limits. This was demonstrated by one early headnote writer, Lord George Lewin, whose terse summaries tended to confuse rather than elucidate. In his headnote to Clement’s Case, reported in 1830, a case relating to a stolen horse, he boldly stated that the case stood for the proposition that ‘possession in Scotland evidence of stealing in England’.[15]

29. While headnotes accompanying cases in the present day are certainly not as brief, nor are the cases that occupy the pages of the law reports getting simpler, owing to trends such as the increasing amount of legislation requiring interpretation and application, and the increasing need to apply established principles to novel cases in an increasingly fast-paced world.

30. Capturing the essence of a case, taking complexity in both the facts and the reasoning, and distilling it into an intelligible summary of only a few paragraphs, is no small feat. It takes time, intelligence, analysis and rigorous reading, and re-reading, of a case. The reports that we all use in our day-to-day work stand as a testament to the skill and dedication of law reporters.

Conclusion

31. To equate accessibility to the law with access to more cases is misguided. Our notions of accessibility should be more nuanced. Access to the law is best served by making the contents of judgments intellectually accessible and relevant.

32. It is in this light that high-quality law reporting is vital, more now than ever. As sources of information, both legal and non-legal, proliferate, and as legal databases grower ever larger, the preservation of a robust system of law reporting is invaluable. The production of high quality law reports — series which report the right cases, with crisp, clear headnotes — remains a vital cornerstone of the rule of law.

A celebration of law reporting

Response by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content at ICLR

1. First of all I’d like to thank Her Honour Justice Button and the Victorian Council of Law Reporting for co-hosting this evening’s event and say how delighted we are to be able to travel again from London to this and other jurisdictions, after the long confinements of the pandemic and the somewhat mixed joys of virtual conferencing.

A time of change

2. The pandemic has certainly had a profound effect on the administration of justice. We’ve just come from a conference at which all the law librarians recalled the effect it had on their ability to support the needs of their users, and I assume it must have had a similarly drastic effect on the conduct of litigation over here as it has had in our own jurisdiction.

3. In particular, it has boosted both the pace of development of modern technology in the courts and the rate of acceptance by both bench and bar. I won’t go as far as saying they all took to it like ducks to water, but necessity was certainly the mother of invention when it came to doing remote hearings with digital bundles instead of attending physical courts cluttered with lever arch files full of printed out documents.

4. While I’m less sure about the judiciary, many barristers seem now to prefer remote hearings, particularly for shorter matters that don’t involve witnesses or a jury. Our law reporters have also adapted well to working remotely, and the fact that all Supreme Court and most Court of Appeal civil hearings are not only streamed but also available on catchup is a boon to reporters, as well as a welcome boost to open justice.

5. These changes in the conduct of litigation, along with the development of online dispute resolution, have been as profound in their way as the reorganisation of the courts in the 1860s and 1870s, which was the context for the establishment of the Council of Law Reporting.

The reporter’s task

6. Interestingly, there was a proposal at one of the founding committee meetings that the new Council should undertake to report every single judgment. That would have anticipated the advent of the internet and the blanket coverage of the legal information institutes by about 130 years. But it wasn’t economically viable.

7. Instead, the Council adopted the now well established recommendations of Nathaniel Lindley QC, whose well known canons Justice Button has already adumbrated. Lindley, who was later Master of the Rolls, also observed that “collections of rubbish must be carefully avoided”.

8. We are acutely conscious that while the Bar always want cases to be reported, to advertise their brilliance, the Bench tend to want fewer cases reported. Our selective approach to reportability means that we report the cases that matter, and avoid the evils of over-citation and duplication.

9. As Justice Button has pointed out, the added value of the law report chiefly lies in the headnote. This adornment seems to have been a relatively late development in the history of law reporting, if you trace that back to the plea rolls of the 12th and 13th centuries. Though many of the Nominate reports appeared with a brief side-note or standfirst identifying the principle recorded in the case, it was only with the reporter Sir James Burrow in the late 18th century – the reporter who covered Lord Mansfield’s court – that the headnote became anything a modern user would recognise.

10. Burrow prefaced his reports with a succinct statement of the facts and issues and the proposition of law decided. The modern headnote is essentially a refinement of that development. It is also a navigational aid, identifying and cross referencing the relevant passages in the judgment, and classifying its contents according to a standardised taxonomy of subject matter catchwords.

11. It is, therefore, the combination of selection and presentation that give the modern law report a value that cannot be found in the judgment alone.

12. That’s not to say that unreported judgments should not be published. We should show the court’s workings for the purpose of transparency and public legal education. The judgment is part of the public record, and should be archived as such – something belatedly recognised by the Ministry of Justice in England, where earlier this year The National Archives launched its own judgments database, Find Case Law. The public have a right to know what the courts are doing in their name. Litigants need to be able to see how their own case is likely to be treated. Justice must be seen to be done. As Jeremy Bentham famously observed,

“Publicity is the very soul of justice. It is the keenest spur to exertion and the surest of all guards against improbity. It keeps the judge himself while trying under trial.”

13. Law reports are part of open justice but they also have a more specialised role, supporting legal education and the administration of justice. Those were the purposes for which the council was set up and has continued for over 150 years.

Our wider mission

14. As a charity, we feel our mission goes wider. And in recent years the ICLR has begun to find other ways of promoting access to justice and legal education.

15. Our support for legal education now includes an annual pupillage award. Pupil or trainee barristers are paid in England and Wales, but the minimum award is barely enough to live on. And for those in chambers doing publicly funded work (which is now so badly paid that criminal defence barristers are on strike) we offer the winning applicant a substantial top-up award of an additional £13,000. The award is means tested to ensure it goes to someone who really needs it, and is dependent on completing a challenging written assignment.

16. ICLR is supporting access to justice in other common law jurisdictions in collaboration with the Lead Judge for International Relations, Lord Justice Dingemans. This has included, most recently,

- providing training and support for the Botswana Law Reports. We’re hosting a visit by a team of their reporters and editors later this year.

- providing free access to materials for the Law Commission of Somaliland, in conjunction with the Judicial Office; and

- promoting and supporting the International Law Book Facility, which facilitates the donation of law books to organisations and common law jurisdictions in the third world who can’t afford to buy them.

17. Meanwhile, back at home, we’ve kept up with the times by developing tools to help users research and find case law. So our new Case Genie service utilises the power of Artificial Intelligence to locate and recommend cases which are similar or related to the legal issues in written content (such as a skeleton argument) uploaded by the user. We’ve brought a leaflet explaining how this works, in case anyone here would like to know more, and of course we’d be happy to talk about it or set you up with a trial.

18. But in the meantime I suspect you’d like to enjoy a drink. Thank you all again for coming.

Footnotes

[1]Judge of the Trial Division of the Supreme Court of Victoria; Chair, Council of Law Reporting in Victoria. This is an edited version of a speech delivered to a joint event of the Victorian Council and the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting England and Wales on 29 August 2022. I acknowledge, with appreciation, the drafting and research assistance of Daniel Lopez and Cate Read.

[2]Owen Dixon, ‘Concerning Judicial Method’ in Susan Crennan and William Gummow (eds), Jesting Pilate (Federation Press, 3rd ed, 2019) 112, 116-7. See also Stephen Gageler, ‘The Coming of Age of Australian Law’ in Barbara McDonald, Ben Chen and Jeffrey Gordon (eds), Dynamic and Principled: The Influence of Sir Anthony Mason (Federation Press, 2022) 8, 8.

[3]Lord Carnwath of Notting Hill, ‘Judicial Precedent: Taming the Common Law’ (2012) 12(2) Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal 261, 261–72, quoting Lord Neuberger, ‘Law Reporting and the Doctrine of Precedent: The Past, the Present and the Future’ in Halsbury’s Laws of England Centenary Essays (LexisNexis, 2007) 69, 71.

[4] Greg Wurzer, ‘The Legal Headnote and the History of Law Reporting’ (2017) 42(1) Canadian Law Library Review/Revue Canadienne des Bibliothèques de Droit 10, 13-14.

[5] ibid.

[6] Lord Neuberger, ‘No Judgment — No Justice’ (Speech, First Annual BAILII Lecture, 20 November 2012) <https://www.bailii.org/uk/other/speeches/2012/BAILII1.html>

[7] Slater v May (1704) 2 Ld Raym 1071, 1072, cited in Lord Neuberger, ‘No Judgment — No Justice’ (Speech, First Annual BAILII Lecture, 20 November 2012) <https://www.bailii.org/uk/other/speeches/2012/BAILII1.html>

[8] Steven Rares, ‘Authorised Law Reporting’ (Speech, Remarks to welcome to Australia the Incorporated Council for Law Reporting for England and Wales, 9 May 2018) <https://www.fedcourt.gov.au/digital-law-library/judges-speeches/justice-rares/rares-j-20180509>

[9] William Cornish et al, Oxford History of the Laws of England (Oxford University Press, 2011) vol XI, 1215. See also Steven Rares, ‘Authorised Law Reporting’ (Speech, Remarks to welcome to Australia the Incorporated Council for Law Reporting for England and Wales, 9 May 2018) <https://www.fedcourt.gov.au/digital-law-library/judges-speeches/justice-rares/rares-j-20180509>

[10] Nathaniel Lindley, ‘The History of the Law Reports’ (1885) 1 Law Quarterly Report 137, 143. See also Michael Bryan, ‘The Modern History of Law Reporting’ [2012] (December) (11) University of Melbourne Collections 32, 35.

[11] Steven Rares, ‘Authorised Law Reporting’ (Speech, Remarks to welcome to Australia the Incorporated Council for Law Reporting for England and Wales, 9 May 2018) <https://www.fedcourt.gov.au/digital-law-library/judges-speeches/justice-rares/rares-j-20180509>

[12] Michael Bryan, ‘The Modern History of Law Reporting’ [2012] (December) (11) University of Melbourne Collections 32, 32

[13] Haxton J Naida, A Manual on Law Reporting (Law Foundation of New South Wales, 1991) 20.

[14] ibid.

[15] Clement’s Case (1830) 1 Lewin CC 113, quoted in TF Bathurst, ‘Remarks on 50th Anniversary’ (Speech, Council of Law Reporting for New South Wales, 29 October 2019) <https://www.supremecourt.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/Publications/Speeches/2019%20Speec hes/Chief%20Justice/Bathurst_20191029-2.pdf

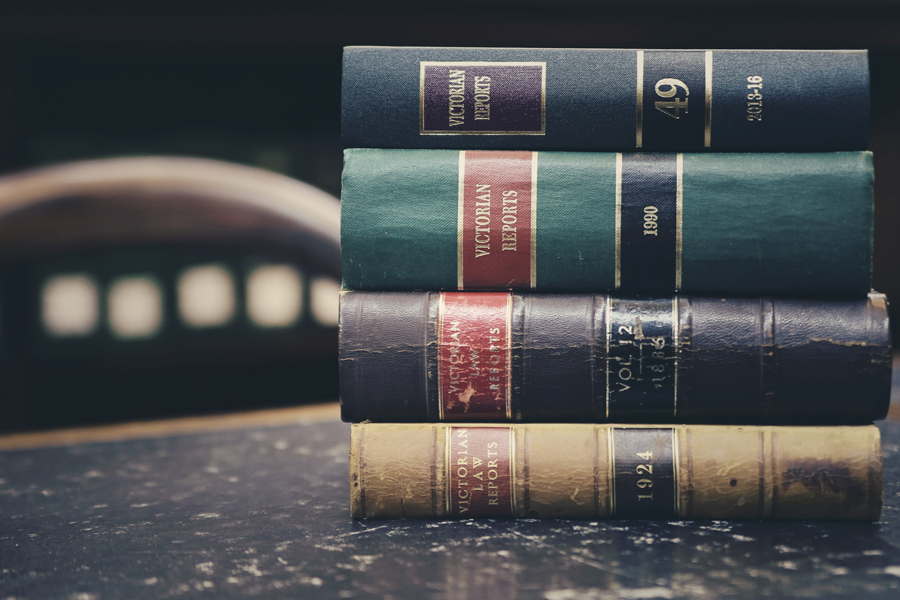

Featured images: The Law Library of Victoria, in the Supreme Court in Melbourne; and the Victorian Law Reports. We are grateful to the Law Library for allowing us to use these images.