Life at the Bar: A North-South Divide?

Barristers’ Working Lives: a second biennial survey of the Bar (2013) was jointly published by the Bar Council and Bar Standards Board on 18 June. In this post, we look at some of the results and implications of this snapshot of life at the Bar. In particular, we look at the effect of cuts in… Continue reading about Life at the Bar: A North-South Divide?

Barristers’ Working Lives: a second biennial survey of the Bar (2013) was jointly published by the Bar Council and Bar Standards Board on 18 June. In this post, we look at some of the results and implications of this snapshot of life at the Bar. In particular, we look at the effect of cuts in legal aid and publicly funded work on the prospects and attitudes of those working in both the employed and independent Bars.

You can read the full report here (PDF).

A tale of two Bars

The “North-South” divide of the title of this post is not a geographical one, it’s just recyling a media cliché for economic inequality. It refers to a theme than runs through almost every section of the report, which is the very different experiences of those sections of the Bar relying wholly or mainly on publicly funded crime and family or small claims civil work (the North) and those working for private clients in commercial and chancery work (the South).

Another divide is between the Regulatory (BSB) and Representative (Bar Council) roles of the bodies responsible for the report. According to the “Regulatory Foreword” of Baroness Deech QC (Hon), Chair of the Bar Standards Board,

The Bar Council’s representative role requires quite a different focus to the Bar Standards Board’s statutory and regulatory one. Given these competing demands the Bar Standards Board considers that a jointly-commissioned and published document of this nature is unlikely to meet our future needs for information so this will be the last biennial survey in this joint format.

This signals an intention – probably at the behest of the “regulators’ regulator”, the Legal Standards Board (LSB) – that the regulatory bodies distance themselves still further from those representing the interests of the various legal professions (barristers, solicitors, legal executives et al). Regulation, it would appear, is now more focused on protecting consumers, rather than maintaining the quality and reputation of the profession (although these are essentially different sides of the same coin). Baroness Deech calls for an “outcomes-driven approach” which provides the “correct incentives for ethical behaviour” based on “the ability to profile the regulated community according to the level of risk” to consumers. That sounds like a true regulator speaking.

By contrast, the Bar Council chairman, Nicholas Lavender QC focuses on the risks to the profession with so many at the Bar feeling dissatisfied with their falling earnings and increasing workload, with the prevalence of bullying and discrimination (especially of those in the employed sector) and with the number expressing an intention to leave and work elsewhere. But as he notes, there are “marked differences between different sectors of the Bar”, which brings us back to that North-South divide.

Key findings

The survey was completed by 3,300 barristers from all sectors of the profession. Over three-quarters (78%) of barristers still work as independent practitioners in chambers, but the majority of these are male (65%). The fact that fewer women stay at the independent Bar (the number decreases as the time since call increases) has serious consequences for diversity on the Bench, unless we are to contemplate the idea of a career judiciary (perhaps based on a minimum of seven years’ call or practice). But that is a debate for another day.

By contrast, of the 16% who worked at the employed Bar, the proportion of women remained about 50:50. Of those working in the employed Bar, just over half work in the public sector, mainly for the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) or the Government Legal Service (GLS). However, the numbers have fallen, particularly among criminal practitioners, 90% of whom worked in the public sector at the time of the previous report, in 2011, but only 73% did so in 2013. Over the same period, the number working in solicitors’ firms has increased, from 13% to 22% of the employed Bar.

Levels of satisfaction

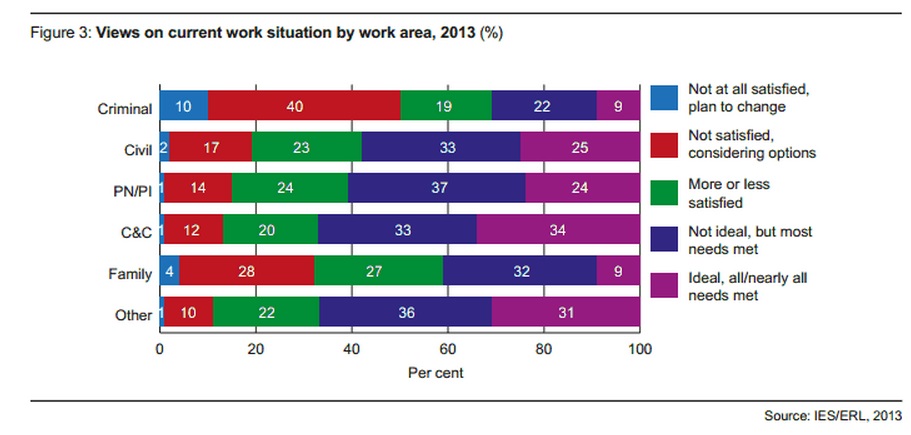

Crime is still the biggest practice area, with 31% of all barristers (43% of the employed Bar). And it is in crime that dissatisfaction is highest, with 57% reporting decreased earnings (29% substantially) and 75% considered that they were not fairly paid for their work. It’s also the hardest working area, with 20% doing more than 60 hours per week, and another 34% doing 51–60 hours.

Another area with high levels of dissatisfaction is family law, with 39% reporting a decrease in earnings (12% substantially), and 49% considered themselves not fairly paid for the work they did. As in crime, at least 20% were doing more than 60 hours per week, with a further 29% doing 51–60 hours.

At the other end of the scale, as the above table shows, those working in the commercial and chancery area (predominantly Oxbridge educated, as it happens) reported higher levels of satisfaction with their lot, with 50% reporting increased earnings (19% substantially), and 34% viewing their current situation as “ideal, all/nearly all needs met” (compared to only 9% of the criminal bar).

Bullying and discrimination

Again, when it comes to bullying and discrimination, it seems the criminal and family practice areas come out worse, with 29% of those working in crime at the employed Bar reporting incidents, and 35% within the CPS, and at the independent Bar the highest level being in the family practice area. Bullying, harassment and discrimination related mostly to gender (48%), with pregnancy/maternity featuring highly (12%), and came mostly from other barristers in chambers or from a manager of employed barristers. In general, women felt the Bar was not a family-friendly area in which to work, despite the widely welcomed (but under-used) provision of a nursery by the Bar Council.

Other factors engaged by bullying or discrimination were disability (some 4% of the Bar being disabled), ethnicity (about 10% of the Bar being from Black or Minority Ethnic (BME) backgrounds), and sexuality (3% of barristers said they were gay male, two per cent bisexual, one per cent gay woman/lesbian, and one per cent “other” – whatever that means).

Pride and prospects

Despite the downsides, most were proud to be barristers and found their work interesting and varied. A high proportion (39%) said they did pro bono work, which demonstrated a commitment to law as a public good, and 28% said “making a difference to society” was important to them. Nearly 70% thought the Cab Rank Rule was an important principle to maintain. Awareness of what the Bar Council did for the profession was generally high, with most of its services being regarded as useful; but less than one in five thought the BSB was an effective regulator.

What they didn’t like was the unpredictability of their workload and their earnings. Among those planning to leave the profession altogether, the two main reasons given were legal aid cuts (78%) and workload/stress (48%).

Significantly, only 51% of barristers would opt for the Bar if they could go back and start their careers again, and only 40% would positively recommend the Bar to others as a career. Even allowing for the fact that the grass is often greener elsewhere, that still seems a pretty gloomy outlook.