Judges on strike: could it happen here?

Judges in Egypt have threatened to go on strike in protest against a decree, issued by new president Mohammed Mursi, the terms of which place the president above any law and declare that his decisions cannot be challenged. According to reports from the International Business Times, the decree purports to give the president immunity from

Judges in Egypt have threatened to go on strike in protest against a decree, issued by new president Mohammed Mursi, the terms of which place the president above any law and declare that his decisions cannot be challenged.

According to reports from the International Business Times, the decree purports to give the president immunity from his country’s judiciary and ensures his decisions cannot be revoked.

In these circumstances, the judges have every right to be concerned. For such a move would strike at the very foundations of the rule of law.

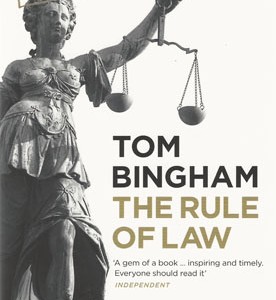

As the late Tom Bingham (aka Lord Bingham of Cornhill, one of the greatest British judges of recent times) pointed out in his book The Rule of Law (2010), chap 3, the core of that principle is that

all persons and authorities within the state, whether public or private, should be bound by and entitled to the benefit of laws publicly made, taking effect (generally) in the future and publicly administered in the courts.” (Emphasis added.)

Bingham identifies a number of key events in English constitutional history by which this principle was achieved. The first of these was Magna Carta, signed by King John in 1215, which represented “a clear rejection of unbridled, unaccountable royal power, an assertion that even the supreme power in the state must be subject to certain overriding rules.” Though at the time legislative, executive and judicial powers were concentrated in the king, supposedly the Lord’s Anointed, with Magna Carta “he became subject to the constraint of the law.”

Mursi appears to have arrogated to himself exactly the sort of sweeping powers King John once assumed he enjoyed. He has sacked the country’s general prosecutor and taken over the police force. His decree, as read out by a spokesman, states that: “The president can issue any decision or measure to protect the revolution. The constitutional declarations, decisions and laws issued by the president are final and not subject to appeal.”

Egypt’s highest body of judges, the Supreme Judicial Council said, “Morsi’s decree is an unprecedented assault on the independence of the judiciary and its rulings”. Courts in the Mediterranean city of Alexandria have announced a work suspension and the Judges’ Club, which represents judges throughout the country, called for a nationwide strike. “We were confident that maintaining the independence of the judiciary’s service was the starting point for achieving a state that respects the rule of law, and a genuine democratic state would be the foundation for the prosperity of the nation,” said the judges’ body in a statement. It is hard to imagine judges in England going on strike, and indeed they have on occasion (applying the law of the land) had to issue injunctions and other orders effectively stopping those in other occupations from downing tools. Nor are we likely to see in our lifetime the sort of constitutional crisis that would make English judges resort to such a move to defend their independence, though they are apt to protest in other ways, eg by writing to the newspaper. (There’s nothing like a wig for keeping a stiff upper lip.) By contrast, judges of other nations have been more easily provoked. According to The Jurist, in September this year

“Greek judges and court employees assembled in front of the country’s Supreme Court in Athens to protest proposed pay cuts under the austerity measures for 2013-2014 which will eliminate public sector jobs and lower wages and pension plans. Around 200 judges, public prosecutors and court workers announced that they will cut the operating hours of courts if the proposed new cuts are approved.

The same source reports that in May this year

“Judges in Tunisia went on strike to protest a decision by Justice Minister Noureddine Bhiri to fire more than 80 judges. According to the head of the Judge’s Union, Raoudha Abidi, the judiciary’s open-ended strike will not end until Bhiri reverses his decision to terminate the judges’ employment and allows the fired judges to defend against the allegations of corruption in a trial setting. Abidi noted that the judiciary is not defending the allegedly corrupt judges, but is instead calling for the government to allow for each judge to defend their actions and have a fair trial.”

Well, if there’s one thing judges ought to be keen on, it’s a fair trial. Once again, Magna Carta is our touchstone, as Bingham makes clear in his book, for although it may not have resulted immediately in a fair system of trials, it lodged the idea in the minds of the people that such a process was possible, imaginable, even realisable. The ducking-stool days were, if not over, at least numbered.

Well, if there’s one thing judges ought to be keen on, it’s a fair trial. Once again, Magna Carta is our touchstone, as Bingham makes clear in his book, for although it may not have resulted immediately in a fair system of trials, it lodged the idea in the minds of the people that such a process was possible, imaginable, even realisable. The ducking-stool days were, if not over, at least numbered.

More reports of judges striking around the globe (I had not realised what a common phenomenon it is turning out to be) include (again from the Jurist):

February 2009: “Judges from more than 30 Spanish provinces went on a one-day strike to demand that the country’s judicial system hire more judges and adopt electronic technology to decrease the workload faced by current judges.”

July 2008: “Italy’s National Association of Magistrates voted to proclaim a “state of agitation,” preparing for a possible strike over anticipated judicial budget cuts by the government of Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. Judges argued that the proposed cuts would drastically reduce the judiciary’s ability to combat lawlessness. The judges also expressed frustration over government efforts to finalize legislation that would suspend ongoing corruption proceedings against Berlusconi.”

March 2007: “Ugandan judges agreed to call off a strike after President Yoweri Museveni wrote a letter to the judiciary, expressing regret for a March 1 siege of the Ugandan High Court. The judges went on strike to protest the incident, in which state security agents surrounded the courthouse and rearrested six defendants who had been granted bail. The defendants’ lawyer was also beaten unconscious by security forces. Ugandan judges and international legal groups decried the siege as an attack on the independence of the Ugandan judiciary.”

These doughty defenders of the rule of law deserve our support, I feel. But there’s a more personal interest at stake. What if English judges were to go on strike? What if, for example, they were so incensed at Justice Minister Christopher Grayling’s planned “crackdown” on “weak, frivolous and unmeritorious” judicial reviews (as reported in Solicitors Journal last week) that they decided it represented an unwarranted assault on the independence of the judiciary (which it doesn’t, it’s just political noise)? As with any strike, there would be consequences. Cases would pile up, the listing officers would have to twiddle their thumbs, barristers’ clerks would exchange despairing anecdotes about returned briefs and idle silks overdoing long lunches; and Pommeroy’s wine bar would be full of unused counsel wondering what on earth to do with themselves, or bragging improbably about their busy non-court paperwork.

Of course it would never happen. But if it did, there’s one class of professionals whose very existence would be called into question. The law reporters.

For what can a law reporter do, if there is no law to report? The great common law tradition of England is founded on the notion that judges develop the law, incrementally, precedent by precedent, in their judgments. If judges don’t give judgments, reporters can’t report them. Only last week, one of our most senior judges, the President of the Supreme Court, Lord Neuberger, reiterated the crucial role played by law reporters in the development of the common law, by providing clear, accessible, reliable reports of precedent-setting cases. (BAILII lecture “No Judgment, No Justice”, reported here).

Although law reporting does not play such a role in most of the jurisdictions discussed above, the fact remains that in a democratic society which respects the rule of law, the administration of justice depends on a number of independent, impartial professionals. Of these, judges are clearly the most important. But for a justice system to work, all the professionals in it need to be professionally motivated. Their status must be protected, if necessary by the extreme measure of going on strike. Despite the apparent frequency of its use, as reported herein, it is not a measure to be used lightly. Let’s hope the situation in Egypt resolves itself soon.