Crown and court, continuity and change: the implications of a monarch’s accession for the legal system

Elijah Granet reflects on the long association of the Crown and the law, and looks back (and forward) to what happens when a new king or queen takes over

As the country celebrates the seventieth anniversary of the Queen’s accession to the Throne, it is worth reflecting on how a change of monarch impacts the legal system.

These changes are less drastic than they used to be. Once, the demise of the Crown meant that the King’s Peace expired, and until the coronation of the new king, the courts of the Crown had no power to enforce the criminal law; the death of Henry I is supposed to have sparked an anarchic phase of robbery en masse. Fortunately, in 1272, as recounted by Sir Frederick Pollock, when Edward I was off crusading, it was decided that the King’s Peace would continue uninterrupted when the Crown changed hands, since it would be unworkable to put the Crown out of legal action until the King finally returned from the Middle East.

It was also once the case that each demise of the Crown required all serving judges and other legal officers to be re-appointed and re-sworn in; to avoid temporarily having no judges in the brief period before their mass re-appointment, the short and simple Demise of the Crown Act 1901 means that all judicial officers continue in office when the Crown changes heads. Judges do still renew their oaths to the new Queen as the Act does not affect (as with MPs) the need to swear to the new monarch; Hansard records the Lord Chancellor (Lord Simonds) confirming the judges of the UK did precisely that in 1952. This tradition may not be strictly necessary (the Oath of Allegiance taken by judges already requires them to bear true faith and allegiance to the Queen’s heirs and successors) and the 1901 Act probably forecloses any need to swear again, but the symbolic renewal of oaths is nonetheless an important sign of fidelity to the new sovereign.

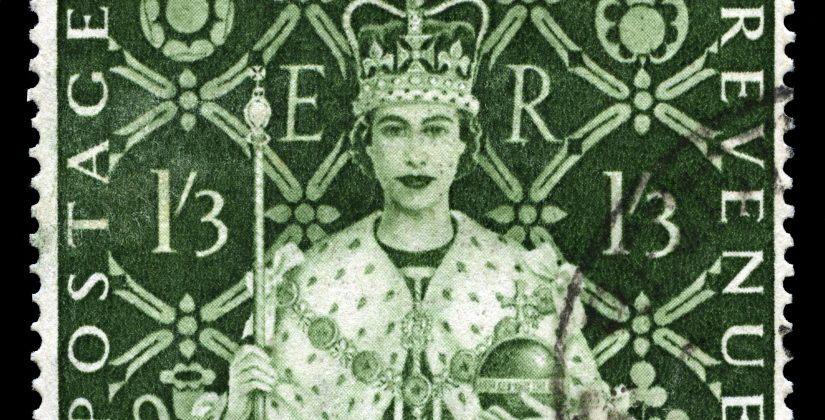

At the next Demise of the Crown, jurors’ oaths will, overnight, stop mentioning “Our Sovereign Lady” and instead mention our “Our Sovereign Lord”. Prosecutions will still be styled R v Smith, but the “R” will stand for “Rex” not “Regina” and judicial review cases will, in their headnote, read “The King on the application of” instead. Architecturally, where once war, union, and dynastic changes meant that the Royal Arms changed from monarch to monarch (most notably with the ugly marshalling of the Arms of Hanover with the accession of George I), the Royal Arms have been more or less stable since the accession of Queen Victoria. When the Queen succeeded her father in 1952, there was to need to change the Royal Arms which feature behind the judge in almost every court in Great Britain, and there will be no need to change them in British courts (or indeed the courts in British Columbia which still inexplicably use the British Royal Arms) when the Prince of Wales accedes to the Throne. The crowns and arms on official seals of courts will go unchanged, and only the stamps used to mail official documents will bear any visual alteration.

The most noticeable change will be for Her Majesty’s Counsel and their stationery. The original Queen’s Counsel, under Elizabeth I, were not permanent appointments but rather employed throughout various cases, and this system was initially informally continued by James I (with the advocates taking the title of King’s Counsel). However, in 1604 Francis Bacon convinced James I to issue a patent appointing the advocate to the office for life, since which all Q/KCs have held letters patent appointing them as one of Her or His Majesty’s Counsel. These lifetime appointments mean that, much like the Queen’s Remembrancer automatically becomes the King’s Remembrancer, QCs will, at the demise of the Crown automatically become KCs overnight. The effect is instant; reports from 1952 note some barristers began their cases as KCs only to finish their arguments later that day as QCs. (These are probably apocryphal or limited to peripheral courts, as the Lord Chief Justice adjourned the case he was hearing when the news made it to court that sad day.) The expense on stationery, nameplates, and letterheads will likely be considerable. When the current Queen acceded to the throne in 1952, the Telegraph reported that there were two living counsel (Lord Cecil of Chelwood and Nathaniel Micklem, aged 87 and 98 respectively), who had been appointed QCs by Victoria, become KCs, and reverted to QCs. Any living people appointed KCs c. 1951 still alive will thus automatically return to their original title at the next demise of the Crown.

There will be sartorial changes, temporarily anyway. On February 8 1952 (two days after George VI died), the Daily Mail archives report of Queen’s Counsel (the new title having set in by then) wearing their “weepers” and mourning bands into court (junior counsel only wear the latter). Mourning bands are pleated barrister’s bands, while weepers are special cuffs used to dry eyes. Sir Henry Brooke, a former High Court Judge, reports the last time these were worn in court was for the death of the Norwegian King (a descendant of Edward VII) in 1991. Even in these more informal times, we can presume that some effort will be made to follow this sartorial tradition at the next demise of the Crown.

Featured image: A vintage British postage stamp celebrating the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II (via Shutterstock).