A visit to the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg

The European Court in Luxembourg enjoys a level of support and quality of facilities that domestic courts, with the possible exception of the UK Supreme Court, can only envy. Before issuing its multi-lingual judgments, the judges have the benefit, not only of a superb modern library, but also the intensively researched opinion of an Advocate General, the nature of whose role is perhaps not as well known as it could be.

Flags and towers

While attending the International Association of Law Libraries 37th annual course in Luxembourg earlier this month, ICLR delegates were taken on a tour of the Court of Justice of the European Union, and heard a presentation about the work of an Advocate General to the court.

The court is located in the Kirchberg district of the city which might be characterised as its Bureaucratic Zone (a non-central business district, to the north east of the old fortified town). This area is full of international banks, university buildings and European Union institutions. The EU Parliament is here. But the Court is stands out by virtue of its distinctive gold towers, which loomed up behind our hotel on the Avenue JFK.

Having passed through security (which was intense, including a passport check) we crossed a broad open space like a parade ground before entering the main court complex. Along one side of this open space, spread out before the gold towers, a row of flags fluttered from their poles. At the far right end of the line was the British union flag. There was a smaller version of this display of flags inside the building, in front of which several of us posed. We wondered for how much longer the union flag would remain.

We’ve had to put up with a certain amount of chaff about Brexit, at this conference, for which we are as apologetic as the American delegates have had to be about their current President. But there was unprompted and apologetic acceptance on the part of other European delegates, that the EU’s own politicians had not been as accommodating as they might have been to the reluctance of some member states or substantial parts of their populations to share in the ‘ever closer political union’ their leaders had once signed them up to.

The Library

Complaints about the lavish funding of EU institutions while domestic economies languish under austerity might not be unfair, either. At any rate, there was no sign here of any of the cost cutting that has crippled the justice system back home. The corridors are lined with art and sculpture, the canteen and other staff facilities seem well provided for, and what we saw of the library was enough to indicate that few researchers would be stuck for published textual sources in any of the EU member languages.

But we only saw part of the collections, housed here in the main working space, with its elegant lighting and IT facilities. The bulk of the print collections are in an annexe, we were told, along with collections of non-member state language texts, and all periodicals. One rather notable absence was a copy of Magna Carta, which used to occupy a glass display case in the main lobby area of the library.

Several shelf stacks were marked with a union flag for the UK (not apparently sub-divided into its three separare jurisdictions) with a number of familiar textbooks in disappointingly old editions. But one assumes the more up to date editions will be held electronically. Likewise the print edition law reports. We were told they were stored with the periodicals, rather than as books; but one assumes most people will now access them online.

Not sure for how much longer UK law books will be in the library though… pic.twitter.com/97ZL0TSqLe

— Paul Magrath (@Maggotlaw) October 5, 2018

The courtroom

The main court room is a vast double-height space, over which hangs a tent-like chain-metal canopy of gold. (It’s not just the towers outside — the amount of gold in the décor of this place was enough to prompt several remarks about its Trump-like aesthetic.)

In front of the wide semi-circle of the bench are ranged the tables and stands for the advocates and their teams. At the back of the court there is a surprisingly large amount of public seating, though perhaps some of it for interested parties and media representatives. We were told it is possible for interested members of the public to attend, though they need to apply in advance and will of course be subject to the same security checks as everyone else entering the complex. In that sense, all proceedings are in open court, at any rate if they are oral. Some cases are decided on the papers, though, in which case the demands of transparency are satisfied by the publication of the decision.

There is one judge for each of the 28 member states and 11 Advocates General. The Court may sit as a full court, in a Grand Chamber of 13 Judges, or in Chambers of three or five Judges. For more information, see Curia, The Court of Justice — Composition, jurisdiction and procedures.

Proceedings are not routinely filmed (as they are in, for example, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, or the UK Supreme Court) but there must be audio recording because on each side of the court, on two levels, are ranged the translation booths, where simultaneous interpreters render every spoken word into as many different member state languages as is desired. The default language, and that of the official record of the court, is French. But depending where the reference comes from and who the judges are, everything will need to be translated into one or more likely several other languages.

This is the main court room but there are others, smaller ones designed for first instance hearings or those with fewer judges and parties, and correspondingly fewer translation booths.

It would be nice to think we could ‘borrow’ some of these lovely well-provided for court rooms for our own domestic appeal hearings but that probably isn’t going to happen. (On a previous day we had been taken on a tour of the old town, where the domestic Luxembourg courts are situated: although we didn’t look inside, it seems doubtful they could be as plush as the ECJ.)

The work of the Advocate General

The main function of an Advocate General is to provide the court with a fully researched and considered opinion on a substantive case reference. The opinion is published in advance of the judgment, with its own citation, and in most cases the court accepts the AG’s recommendations as to the decision in law. However, in a minority of cases the court, while relying on the AG’s researches as to the relevant law and the facts, reaches a different decision on a point in issue.

Advocate General Eleanor Sharpston QC explained how she began at the court as a referendaire, assisting and reporting to an earlier Advocate General (later judge of the Court) Sir Gordon Slynn. When a case is referred to the court by a member state, the materials provided by the referring court and the litigating parties may not be as complete as the court would like. What comes into the court, said Sharpston, may be uneven in quality; it may not fully identify the problem, or the relevant legislation and case law, both domestic and European. There may also be relevant Strasbourg (human rights) case law and other international law materials. The AG must ‘fill the holes’ in the materials provided, and do detailed research in order to give the court a complete picture, before expressing a view. In this, the AG is assisted by her own referendaire, as she in turn once assisted Advocate General Slynn as his.

Advocate General Eleanor Sharpston QC explained how she began at the court as a referendaire, assisting and reporting to an earlier Advocate General (later judge of the Court) Sir Gordon Slynn. When a case is referred to the court by a member state, the materials provided by the referring court and the litigating parties may not be as complete as the court would like. What comes into the court, said Sharpston, may be uneven in quality; it may not fully identify the problem, or the relevant legislation and case law, both domestic and European. There may also be relevant Strasbourg (human rights) case law and other international law materials. The AG must ‘fill the holes’ in the materials provided, and do detailed research in order to give the court a complete picture, before expressing a view. In this, the AG is assisted by her own referendaire, as she in turn once assisted Advocate General Slynn as his.

Coincidentally, on my own earlier visit to the court, nearly 30 years ago, Slynn was the AG who gave a talk to our group and explained his role and how the court worked. That was on a trip organised by and for members of the High Court Journalists’ Association (HCJA), with a mixed group of law reporters and court journalists. I am not sure what he made of us, but he was gracious and welcoming and I fear my speech of thanks (as rather juvenile HCJA chair at the time) must have been rather inadequate.

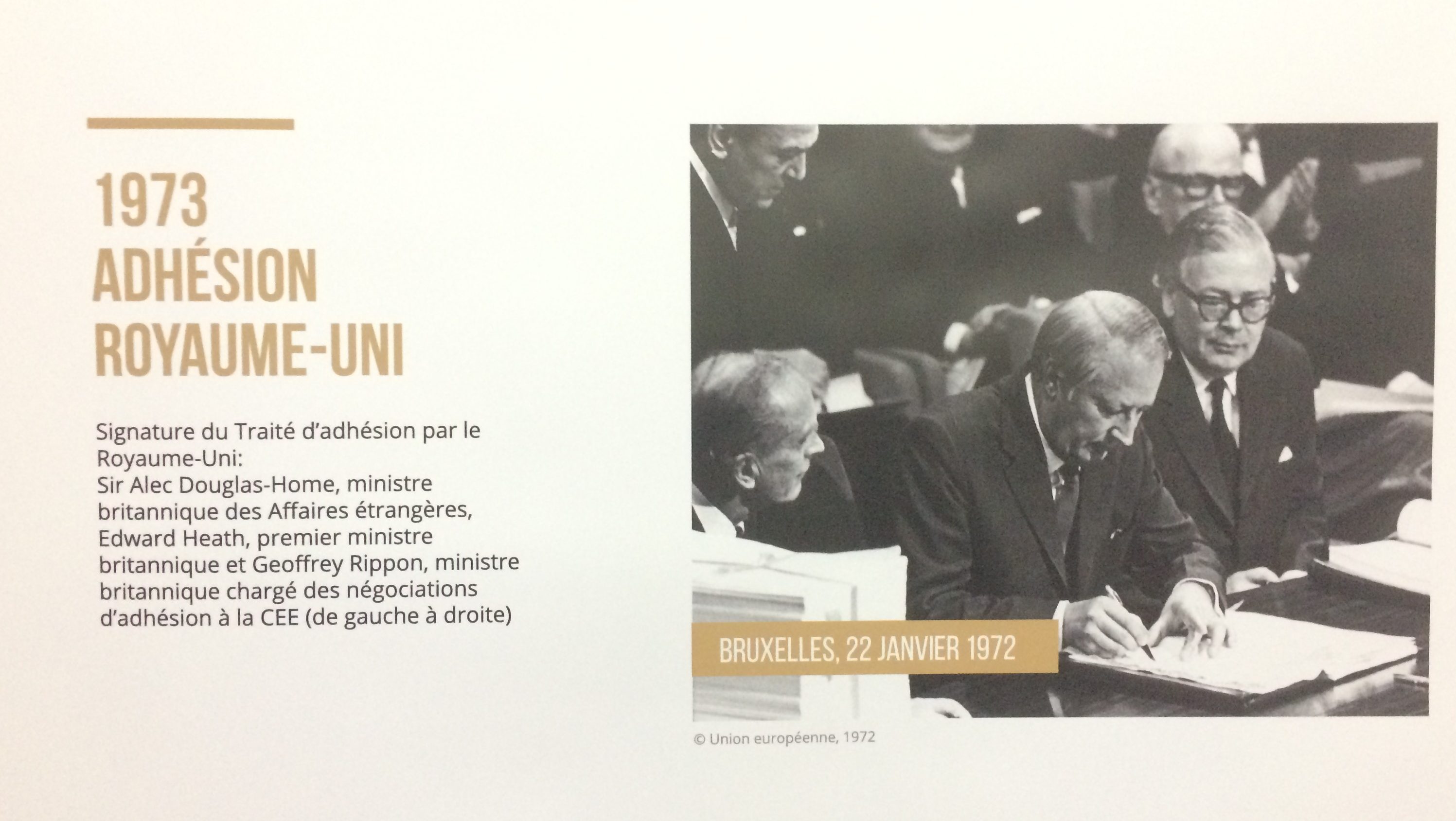

Sharpston AG has been appointed to serve until 2021, but in view of Brexit uncertainty cannot be sure she will complete her term. Among the pictures in the hall outside the court, is a series recalling the treaties of accession of each of the member states in turn. Here is ours.

I wonder if there will be another picture, edged in black, for our de-accession (or whatever the opposite is). Down a corridor towards another part of the complex is a line of portraits of judges and advocate generals. I asked Sharpston if she, too, had a portrait. ‘I will when I retire,’ she said, before remarking that ‘You have to walk quite a long way down that line of portraits before you see a woman judge or advocate general.’

Indeed you do. This was something I had already noted, not least because one of the questions we always used to ask, when visiting foreign courts with the HCJA back in the 80s and 90s, was how many of their judges were women. A recent report by the Council of Europe Commission for the efficiency of justice (CEPEJ) shows that many of the member states are far ahead of the UK in this respect, notwithstanding our recent excitement over a majority female panel on the UK Supreme Court, but it’s clear that the ECJ is even farther behind than the UK (around 25% compared to the UK’s 34%). Well funded, oui; diverse, non.

Neither an advocate nor a general

A word about the title, Advocate General. The AG is not an advocate, the role is essentially a judicial one. Nor is she a general, notwithstanding the absent minded question of one military gent, when told of her rank, ‘Oh really, which regiment?’ Perhaps the old buffer thought it was a court-martial role.

As AG, Sharpston sits on the most junior end of the bench. She does not make submissions, but she may ask questions of the national government’s representatives to clarify and confirm her understanding of their domestic law, and ensure the accuracy of the account of that law on the record.

The presiding judge sits in the middle of the bench, and the judge-rapporteur, usually one of the other judges, is responsible for drafting the judgment. Although the AG researches and reports on the relevant law in her opinion, the judges can and do conduct their own research as well. Given that they may all be working in different languages, it is necessary to ensure there is a common understanding across different legal cultures; and to ensure nothing has been assumed or taken for granted in one culture that might not be, or might be understood differently, in another. The aim of the court is to rule on the law in a way that applies, so far as possible, in the same way across all of the member states.

Such is the work of a court whose case law will continue to be of relevance to common lawyers in the UK for decades to come, whatever sort of Brexit is ultimately agreed. And for that reasons, despite some initial uncertainty, ICLR will continue to report it.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content at ICLR, who was in Luxembourg for the 37th annual course of the International Association of Law Libraries in October 2018.