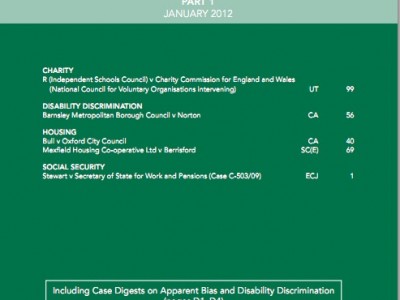

The Public and Third Sector Law Reports: January 2012

Isobel Collins, editor of the Public and Third Sector Law Reports, discusses some of the cases in the latest issue

“a trust which excludes the poor from benefit cannot be a charity”

This is but one of the many pearls to be discovered in the judgment of the Tax and Chancery Chamber of the Upper Tribunal, promulgated on 13 October 2011, on the meaning of public benefit in the Charities Act 2006 and its relation to the charitable status of fee-charging independent schools, now reported by ICLR as Regina (Independent Schools Council) v Charity Commission for England and Wales (National Council for Voluntary Organisations intervening) [2012] PTSR 99.

This is but one of the many pearls to be discovered in the judgment of the Tax and Chancery Chamber of the Upper Tribunal, promulgated on 13 October 2011, on the meaning of public benefit in the Charities Act 2006 and its relation to the charitable status of fee-charging independent schools, now reported by ICLR as Regina (Independent Schools Council) v Charity Commission for England and Wales (National Council for Voluntary Organisations intervening) [2012] PTSR 99.

The expert tribunal, composed of Warren J and Upper Tribunal Judges Alison McKenna and Elizabeth Ovey, considered two closely related cases: one a judicial review claim brought by the Independent Schools Council challenging the Charity Commission’s guidance on public benefit and fee-charging; and the other a reference by the Attorney General (the first under the new statutory procedure) seeking the determination of specific questions concerning the operation of charity law on a hypothetical fee-charging independent school.

The tribunal warns against applying its decision to other heads of charity: “what we say in this decision about the public benefit requirement is confined to the context of educational charities”. However, it does recognise that its analysis of the principles and the case law “may have wider implications”, and I have little doubt that it will.

There is much of interest in this wide-ranging judgment. You will find clarification of the content and meaning of “public benefit” as used in the 2006 Act and how that is relevant in determining (i) whether an organisation is a charity and (ii) whether a charity is operating as a charity in accordance with its duties as a charity. Among many other matters to note are the tribunal’s rejection of the suggestion of a pre-Act presumption, or assumption, that the advancement of education is necessarily for the public benefit, and the conclusion that the provision of a standard education is beneficial.

Of particular practical importance is the tribunal’s conclusion that to operate as a charity a fee-charging school must be seen to be doing enough for those who cannot afford to pay the fees. Such provision must be more than de minimis or merely token, but the tribunal makes clear that it is for the charity trustees and not for the Charity Commission to determine how the requirement should be met. In so far as the guidance imposes a requirement of “reasonableness” it is wrong.

The judgment warrants intensive and prolonged study and I hope that charity law practitioners will find our headnote summary and carefully checked judgment a useful and authoritative reference and study aid both now and in the future.

The PTSR report also helpfully includes the tribunal’s supplementary judgment, given on 2 December 2011, on the specific relief to be granted in the judicial review proceedings. This precisely identifies those parts of the Charity Commission’s guidance (comprising Charities and Public Benefit: the Charity Commission’s General Guidance on Public Benefit (January 2008), and Public Benefit and Fee-Charging and The Advancement of Education for the Public Benefit, December 2008) which will be quashed if not withdrawn by the commission.

Finally, I’d like to take this opportunity to wish our readers and subscribers a very Happy New Year.

The Editor