Children in need

Isobel Collins, Editor, Public and Third Sector Law Reports discusses some of the cases in the issue

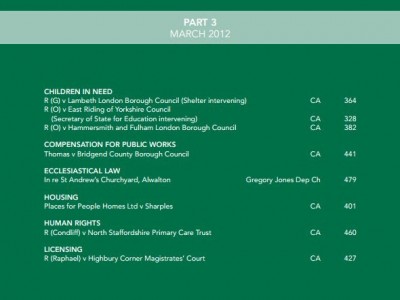

This month’s edition of PTSR includes a trilogy of Court of Appeal decisions concerning various aspects of a local authority’s duties under the Children Act 1989 to children in need. All in the Public and Third Sector Law Reports, providing the best coverage of charity and public law cases.

R (O) v East Riding of Yorkshire Council (Secretary of State for education intervening) [2012] PTSR 328 “raises an interesting and important question about the relationship of the 1989 Act and the Education Act 1996” and about the “local authority’s obligations and powers under section 20 of the 1989 Act to accommodate children, which have given rise to much litigation in recent years.”

R (O) v East Riding of Yorkshire Council (Secretary of State for education intervening) [2012] PTSR 328 “raises an interesting and important question about the relationship of the 1989 Act and the Education Act 1996” and about the “local authority’s obligations and powers under section 20 of the 1989 Act to accommodate children, which have given rise to much litigation in recent years.”

The issue was whether a child’s status as a “looked after child” ended when the local authority provided him with accommodation at a special residential school pursuant to a statement of educational needs (“SEN”). Cranston J held that it did: the accommodation was not provided under the council’s social service functions. The Court of Appeal reversed that decision.

The question of the claimant’s proper status under the legislation was of importance and not just of academic interest, since a local authority has duties to children in need into adulthood and it is, therefore, important to identify those cases where the benefits of looked after child status are available.

Rix LJ pointed out, at para 80, that the House of Lords has made it clear that short shrift is to be given to any claim by an authority that a child who requires accommodation within section 20 can be deprived of looked after child status by being provided with accommodation under another statute or label: see R (G) v Southwark London Borough Council [2009] PTSR 1080, a case involving the relationship between the child in need provisions of the 1989 Act and housing obligations under the Housing Act 1996.

However, it is not in every case that the 1989 Act will trump the Education Act 1996. Rix LJ identifies the relevant issue as whether the council can say that the child does not require accommodation under section 20 of the 1989 Act, as distinct from the 1996 Act. The question was which of one or two regimes were invoked by the claimant’s needs and SEN placement.

Rix LJ, with whom Smith and Richards LJJ agreed, said, at para 114, that on the particular facts of the case it was “impossible to regard the SEN placement as being provided wholly or mainly to meet the child’s educational needs, as distinct from being provided to meet both those needs and the needs for which he had become and was a looked after child.” It was plain, and plain to the council, that he “required full-time accommodation in his specialist placement in order to give him care as well as the educational assistance which his needs , and his parents’ inability to cope with and control him, demanded.”

The council never considered, let alone gave anxious scrutiny to, whether the factors which had led to respite care necessitated a continuation of the claimant’s looked after child status following his placement at the residential specialist school. They merely assumed that that status had come to an end with the ending of the respite care which had brought that status into being and thereby terminated his looked after child status on a false premise and unlawfully: paras 116, 119.

Where the claimant’s needs, social as well as educational had driven the placement, as the looked after child review team had long appreciated, it was impossible to regard the 1996 Act’s SEN regime as supplanting rather than supporting the 1989 Act’s looked after child regime. The 1989 Act was “intended to provide the holistic support for children in need who have, because of the provision of accommodation to them, come within the regime and status of being looked after children”: para 117.

R (O) v Hammersmith and Fulham London Borough Council [2012] PTSR 382 is another case involving an almost identical dispute as to the appropriate accommodation and education to be provided by a local authority for a child in need. The Court of Appeal (Rix, Lloyd and Black LJJ) decide, among other matters, that while the best of interests of a child are relevant in judicial review proceedings concerning the lawfulness of a local authority’s decision to accommodate a child in need under section 20 of the Children Act 1989, the principle in section 1(1) of the 1989 Act that the child’s welfare is paramount does not apply.

R (G) v Lambeth London Borough Council (Shelter intervening) [2012] PTSR 364 concerns the issue whether a local authority, whose housing department had provided a child with accommodation under its Housing Act 1996 duties, was required to treat the child (now an adult) as a “former relevant child” within section 23C(1) of the Children Act 1989 to whom it owed continuing duties. The Court of Appeal (Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury MR, Wilson and Toulson LJJ) held that, in the circumstances, the accommodation ostensibly provided by the council under the 1996 Act was to be deemed to have been provided to G as a child in need under section 20 of the 1989 Act, so that the council owed him the continuing duties claimed.

By Isobel Collins, Editor, Public and Third Sector Law Reports