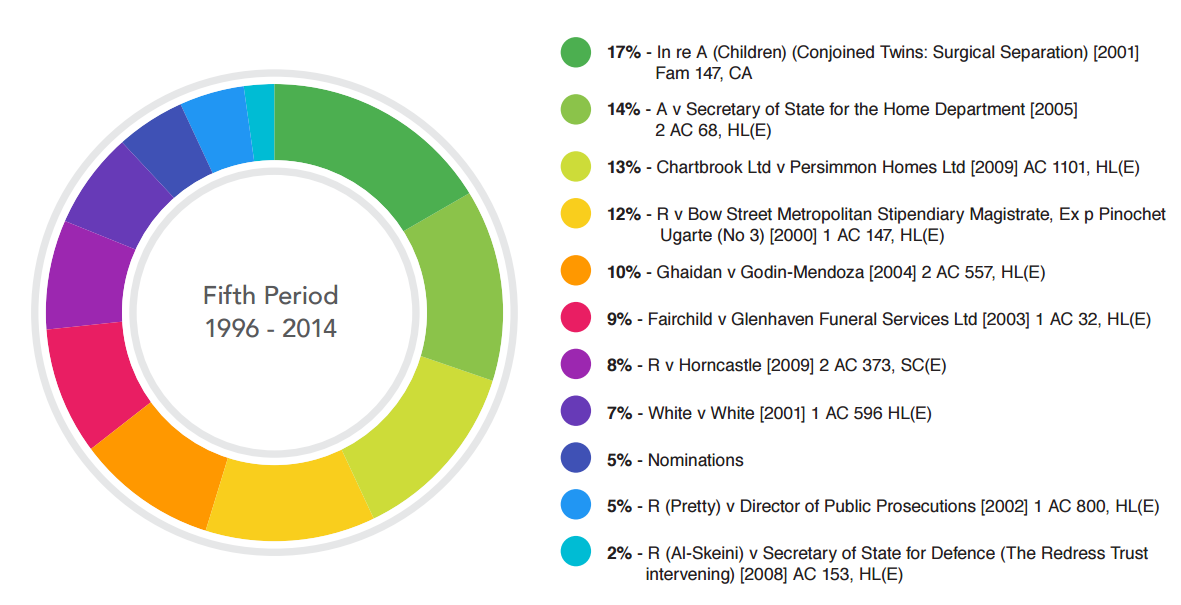

Case Law On Trial – the results: 1996 – 2014

To commemorate the fact that ICLR has been creating case history for the last 150 years, we’re putting together a special Anniversary Edition of the Law Reports, which will include the 15 top cases voted for by you, our readers. We divided our history into five periods, and allowed a month for you to vote for a case from each period.

To commemorate the fact that ICLR has been creating case history for the last 150 years, we’re putting together a special Anniversary Edition of the Law Reports, which will include the 15 top cases voted for by you, our readers. We divided our history into five periods, and allowed a month for you to vote for a case from each period. In this post, we look at the results from the final period, 1996 – 2014.

Though a clear leader emerged with a case that marks a high water mark on the interaction of law with both morality and mortality, the second and third places were closely fought with at least one strong contender coming up a very close fourth. In this last post in the series, we examine the winning cases a bit more closely, and say something about the one that didn’t quite make the cut.

In re A (Children) (Conjoined Twins: Surgical Separation) [2001] Fam 147, CA

There are few cases outside the criminal sphere of which you can say they were a matter of life and death, but this is certainly one of them. It’s the heartbreaking story of a pair of conjoined girl twins whose condition was such that they could not both survive. The hospital having care of them referred to the court the question whether it could lawfully carry out separation surgery the inevitable effect of which would be to shorten the life of one of the twins in the hope and expectation of prolonging that of the other, perhaps even enabling her to live a relatively normal life. The hospital’s application was opposed by the devoutly catholic parents.

Giving the judgment of his career, Ward LJ explored the legal issues in a way that was sensitive to, but not clouded by, the moral and religious aspects. It is rare to find a judgment which can so readily be recommended, despite its length, for reading by those outside the discipline of law, but the case is one which captures the imagination of lay readers in a way not matched by most of the daily business of the courts.

Nor was it surprising, when the novelist Ian McEwan was writing his latest book, The Children Act (2014), to find him paraphrasing at length this and at least one other judgment of Ward LJ (as well as one of Sir James Munby P) to flesh out the moral dilemmas of Fiona Maye, his fictional judge of the Family Division. If that book was not wholly successful in purely novelistic terms, it can at least claim to have drawn wider attention to an aspect of judicial law making about which a lay readership (especially one now fed a constant diet of complaint about “unelected judges” and their preference for human rights over good old fashioned common sense) could feel something not only positive, but perhaps even morally reassuring.

A v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2004] UKHL 56; [2005] 2 AC 68, HL(E)

This case involved nine unnamed terror suspects detained indefinitely in the period following the large scale attacks on the Twin Towers in New York in September 2001. Sometimes called the “Belmarsh” case, after the place of some of their incarceration, it was an early example of the interminable tussle between the demands of national security and respect for human rights.

The House of Lords held, for reasons on which their Lordships were not all agreed, that a derogation order providing for the detention of non-nationals was discriminatory in its effect in a way that rendered it disproportionate and therefore incompatible with the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.

This is perhaps not a judgment to be read for its literary value, rather for its historical and political significance. It reflected a period of increasing authoritarianism in the Labour government of Tony Blair, which before the Millennium had been populist and “feelgood” – think of “Cool Britannia” and the mawkish official response to the death of Princess Diana in 1997 – but after 2001 became hardened by warfare and ever more extravagant in its urge to control every aspect of life. The Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 with which this case is concerned has been described as one of the most draconian ever passed during peacetime.

In its reassertion of respect for the rule of law against the exigencies of a perceived national emergency (though frankly nothing like as threatening to the nation as World War II), the case echoes the sentiments expressed, in the isolation of a prophet before his time, by Lord Atkin in Liversidge v Anderson [1943] AC 206 (which appears earlier in this volume). The caustic indignation with which Lord Atkin seemed to express the opinion, at p 244, that he had “listened to arguments which might have been addressed acceptably to the Court of King’s Bench in the time of Charles I” is echoed, one may feel, by Lord Hoffmann in the present case, (dissenting from the view that there was a public emergency threatening the life of the nation such as to justify derogation from parts of the Convention), at para 97:

“The real threat to the life of the nation, in the sense of a people living in accordance with its traditional laws and political values, comes not from terrorism but from laws such as these. That is the true measure of what terrorism may achieve. It is for Parliament to decide whether to give the terrorists such a victory.”

Even Lord Walker of Gestingthorpe, who declined to support the majority, was prompted to observe, at para 193:

“Whether or not patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel, national security can be the last refuge of the tyrant.”

The majority (seven of the nine Law Lords sitting) decided the case on the basis that, even if there were a public emergency, the power to detain without trial of terror suspects who were not British nationals, but not those who were, rendered the provision discriminatory and inconsistent and it should be struck down on that basis.

Chartbrook Ltd v Persimmon Homes Ltd [2009] UKHL 38; [2009] AC 1101, HL(E)

This case extended the law of contract to permit the court, when faced with a clause that was evidently mistaken in its drafting and made no commercial sense, to “correct by construction” and effectively to rewrite the provision to match what it inferred to be the parties’ intentions based on what was known at the time. The principles expressed have subsequently been used to correct by construction the wording of a statutory instrument, eg in In re Itau BBA International Ltd [2013] Bus LR 490.

The judgment of Lord Hoffmann, explaining the principles on which the court was entitled so to act, has been cited endlessly in later cases (alongside his earlier and equally influential judgment in Investors Compensation Scheme Ltd v West Bromwich Building Society [1998] 1 WLR 896, on more general principles of construction). Together with Attorney General of Belize v Belize Telecom Ltd [2009] UKPC 10; [2009] 1 WLR 1988 (PC), Chartbrook and Investors Compensation Scheme form a trilogy of cases in which Lord Hoffmann has given oft-cited judgments on the question of the construction of documents such as contracts or, in the Belize case, a company’s articles of association. It is a powerful legacy.

The concludes the cases chosen for the ICLR Anniversary Edition which will be launched on Tuesday 6 October 2015 by Lord Neuberger, President of the Supreme Court, at an event in Lincoln’s Inn.

Lord Neuberger will be speaking about his view of the cases chosen and their significance to the long term development of the law of this country.

Included in the commemorative volume is a foreword by the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd, together with a collection of essays on the subject of law reporting. One of these essays, “The Curious Case of the Judgment Enhancers” by Daniel Hoadley (of ICLR) contains a description of the critical role of the law reporter in crafting the headnote of a case, particularly where there are dissenting judgments or where a panel of three or more judges arrive at similar conclusions via different routes. Since the case used as an illustration was the one that came fourth in this final voting period, we think it may be interesting and appropriate to set out the relevant extract here:

A good example of such a case is the House of Lords’ decision in R (on the application of Pinochet Ugarte) v Bow Street Magistrates’ Court (No 3) [2000] 1 AC 147. The case was concerned with the question, inter alia, of whether General Pinochet had immunity under customary international law from allegations of torture by reason of that fact that he was, at the material time, a head of state (immunity ratione personae) and/or that the alleged torture had taken place in the context of his functions as head of state (immunity ratione materiae). The decision was reported in The Law Reports and the reporter was Ms Bobbie Scully, who still reports from the Supreme Court and is also the editor of the law reports appearing in The Times.

To give you a flavour of the scale of the task Ms Scully had in summarising the ratio of the decision in that case, it will help you to know that:

- Seven Law Lords presided, each giving their own speech.

- On the point of whether extraterritorial torture was a crime in the UK before the passing of the Criminal Justice Act 1988, Lord Millet dissented.

- On the point of whether a former head of state had immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the UK for acts done in an official capacity as a head of state, Lord Goff dissented.

- On the point of whether there was universal jurisdiction to prosecute crimes of torture, Lord Hope, Lord Browne-Wilkinson and Lord Saville all offered up their own obiter dicta – dicta falling outside the ratio of the case, but nevertheless relevant to the decision as a whole.

- There were over 80 authorities cited in the speeches and over 50 additional authorities cited in argument.

- So developed was the legal argument, that Ms Scully’s summary of argument ran on for 30 pages, one of the longest notes of argument ICLR has published in 150 years.

- The speeches ran on for over 100 pages.

- Despite the complexity and volume of the material, thanks to the precision with which Ms Scully encapsulated the various holdings in that case, a reader of the report is only required to read a four paragraph headnote to understand the decision, instead of over 100 pages of highly complex judicial reasoning and discourse.

When we think of making information ‘accessible’, we often think in terms of cost and ease of location and retrieval. But, information accessibility is wider than this. The law reporter’s effort, in drafting precise and accurate headnotes, makes the contents of judgments intellectually accessible. Without those headnotes, readers, regardless of their seniority and experience, have to wade into the text of the judgments utterly unaided.

> Back to 150 Years of Case Law on Trial