Case Law On Trial – the results: 1915-1945

To commemorate the fact that ICLR has been creating case history for the last 150 years, we’re putting together a special Anniversary Edition of the Law Reports, which will include the 15 top cases voted for by you, our readers. We divided our history into five periods, and allowed a month for you to vote for a case from each period.

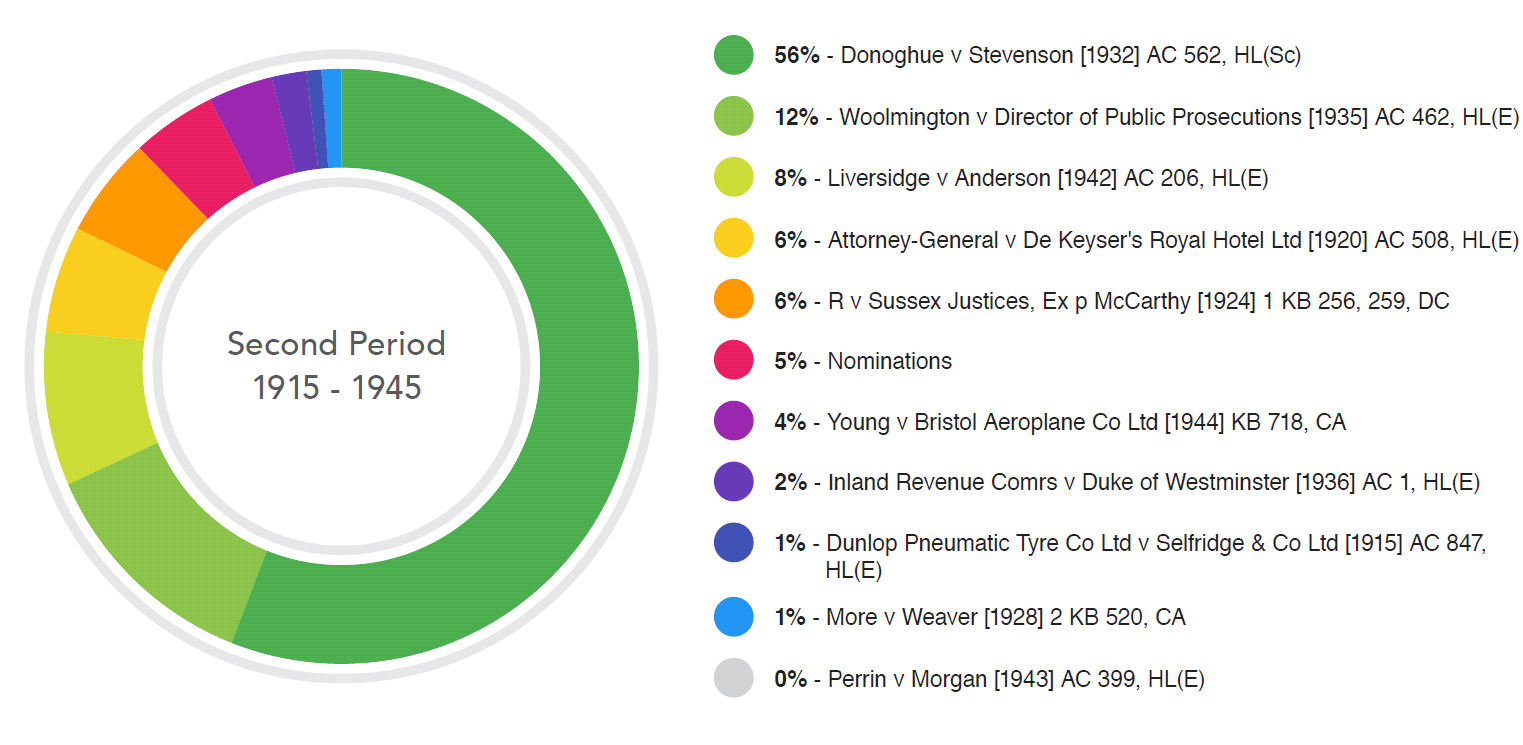

To commemorate the fact that ICLR has been creating case history for the last 150 years, we’re putting together a special Anniversary Edition of the Law Reports, which will include the 15 top cases voted for by you, our readers. We divided our history into five periods, and allowed a month for you to vote for a case from each period. In this post, we look at the results from the second period, 1915-1945.

As this graphic shows, the choice of the top case from our first voting period was both predictable and conclusive. Together with the second and third most voted-for case, it will be included in the special Anniversary Edition, to be published next month to mark our sesquicentenary, or 150th anniversary. In this post we say a little more about the three cases that were chosen for this period, and those that didn’t quite make it.

1. Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562, HL(Sc)

The case about the contaminated ginger beer has lodged itself in the mind of every generation of law students like a snail in the depths of an unguarded bottle. To the modern reader, accustomed to the notion of consumer rights and the blame-and-shame culture, the idea that a negligent manufacturer might not be liable to an injured end-user seems almost outlandish; yet two of the five Law Lords dissented from the judgment of the House.

It was Lord Atkin who was responsible for the oft-quoted definition of legal neighbourliness and his speech is worth reading in full, not least because he wrote so well. He may have thought he was merely tidying up a principle already enunciated by Lord Esher (as Sir Baliol Brett MR) in Heaven v Pender (1883) 11 QBD 503. Yet it turns out he was more or less inventing the modern law of negligence.

For some idea of the mindset of the opposition it is still worth reading the dissenting speech of Lord Buckmaster: he appears like some over-tweeded rambler struggling to release himself from the gorse-like thickets of common law precedent at the foot of the hill, while Lord Atkin climbs ahead towards that eminence from which a clear view of the justice of the case (and others like it) may be enjoyed.

The case has an interesting history, not least because it originated in Scotland and yet is now regarded as a founding authority of the law of negligence in England and Wales as well. It has been the subject of numerous articles and more than one learned monograph, including Matthew Chapman’s The Snail and the Ginger Beer: The Singular Case of Donoghue v Stevenson (2009), which formed the basis of the ICLR Annual Lecture in 2010. (The transcript is available from the ICLR’s own website.) There is also a fine collection of materials on the case on the website of the Scottish Council of Law Reporting including the report of the case in Session Cases, 1932 SC (HL) 31.

Among the questions raised and never satisfactorily answered was – since the case was argued and won on a preliminary issue known as a “plea of relevancy” – whether there ever was a snail in that ginger beer bottle. Having lost the case in the House of Lords, the defender settled with the pursuer and accordingly it was never put to the evidential test, though a myth has grown up that there was no snail in the bottle. But whether the snail was fiction or fact, the decision has continued to have effect, its ramifications echoing around the common law world.

2. Woolmington v Director of Public Prosecutions [1935] AC 462, HL(E)

At a time when the “golden thread” running through the web of English criminal law — that it is for the prosecution to prove the defendant’s guilt and not for the defendant to establish his own innocence — seems to be being whittled away in the name of public order, the prevention of terrorism, fraud, drug trafficking, paedophilia etc, it is useful and instructive to read the whole of the original text of Viscount Sankey LC’s judgment from which it (at p 481) was drawn.

The golden thread, much beloved of Rumpole of the Bailey and other stout defenders of the virtues of liberty and good old fashioned common sense, resurfaces in article 6 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, as scheduled to the Human Rights Act 1998. As for its origin, some see this as dating back at least as far as the extant provision (technically re-enactment) from Magna Carta, providing for a fair trial including a form of jury service. If so, it is appropriate that as well as celebrating ICLR’s 150th anniversary in 2015, this year also marks the 800th anniversary (or octocentenary) of Magna Carta.

The best guarantee of a fair trial is open justice. Proof of the defendant’s guilt, to the criminal standard, must be sufficient to satisfy not only the jury, who are charged with making the decision, but also the public and press in attendance, who the eyes and ears of the public, and to some extent their conscience.

3. Liversidge v Anderson [1942] AC 206, HL(E)

“In this country, amid the clash of arms, the laws are not silent…”

Once again, a speech of Lord Atkin’s stole the show. Although the majority were against him, his view is the one that everyone recalls. The wording of this dictum would appear to be derived from – and issued by way of a spirited riposte to – the saying of the Roman philosopher, Marcus Tullius Cicero, “Silent enim leges inter arma” (usually translated as “In times of war, the law falls silent”).

During World War II, certain wartime regulations gave the secretary of state power to act on the basis of a reasonable belief, in detaining a person believed to be of hostile associations. The House of Lords held, by a majority, that these regulations precluded any inquiry or review of the secretary of state’s belief or whether he had reasonable grounds for it. In other words, the existence of otherwise of a reasonable cause was not a fact into which the court was entitled to inquire in the usual way.

But in his famous dissent, Lord Atkin, at p 244, refused to dilute the rule of law in favour of wartime expediency. In so doing, he seemed almost baffled by the willingness of his majority brethren to toe the official line.

It has always been one of the pillars of freedom, one of the principles of liberty for which on recent authority we are now fighting, that the judges are no respecters of persons and stand between the subject and any attempted encroachments on his liberty by the executive, alert to see that any coercive action is justified in law. In this case I have listened to arguments which might have been addressed acceptably to the Court of King’s Bench in the time of Charles I.

The tension between liberty and security is a difficult one for governments, and has continued to give rise to case law, particularly in the context of the “War on terror”: see, for example, A v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2004] UKHL 56; [2005] 2 AC 68, (another case selected for the Anniversary Edition, from a later voting period, which will be discussed in a later post on this blog).

Liversidge with 8% scored a fair narrow victory over two other cases which got 6% each:

In the context of an earlier war, ie the First World War, the case of Attorney-General v De Keyser’s Royal Hotel Ltd [1920] AC 508 involved the requisitioning on behalf of the Royal Flying Corps of an hotel (whose owner, De Keyser, sounds like a mispronounced version of the enemy leader’s title, Kaiser) without bothering to pay compensation. The House of Lords held that the royal prerogative having been replaced by a statutory power, the authorities were limited by the scope of the statute, under which they were required to pay the Keyser bill.

Alongside Woolmington, another ringing endorsement of the need for a fair trial, R v Sussex Justices, Ex p McCarthy[1924] 1 KB 256, 259 contains a memorable judicial expression of the principle of open justice. Lord Hewart, Lord Chief Justice, reminds us at p 259, that

a long line of cases shows that it is not merely of some importance but is of fundamental importance that justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done.

The opening phrase suggests there may be earlier cases in which this principle has been expressed, but if so they are not cited, and I should be grateful if anyone else can find them. But the phrase Lord Hewart used has passed into common parlance, so much so that it has been riffed into humour, such as to suggest that, in some nations or circumstances, the justice on offer, far from being done, should be “seen to be believed”.

We’ll continue to explore the cases voted for by you, the readers, in further posts in this category (Historic Cases) on the ICLR blog over the next month or so. And you can read the judgments and PDFs of the original law reports of all the shortlisted historic cases on BAILII here.

> Back to 150 Years of Case Law on Trial